Third Edition

This third edition first published 2020

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Edition History

Robert Bucholz and Newton Key (2e, 2009)

Blackwell Publishing Ltd (1e, 2004)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of Robert Bucholz and Newton Key to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Office

111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty

While the publisher and authors have used their best efforts in preparing this work, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives, written sales materials or promotional statements for this work. The fact that an organization, website, or product is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the publisher and authors endorse the information or services the organization, website, or product may provide or recommendations it may make. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a specialist where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data

Names: Bucholz, Robert, 1958– author. | Key, Newton, author.

Title: Early modern England, 1485–1714 : a narrative history / Robert Bucholz and Newton Key.

Description: Third edition. | Hoboken : Wiley, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019024983 (print) | LCCN 2019024984 (ebook) | ISBN 9781118532225 (paperback) | ISBN 9781118532201 (adobe pdf) | ISBN 9781118532218 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Great Britain–History–Stuarts, 1603–1714. | Great Britain–History–Tudors, 1485‐1603. | England–Civilization.

Classification: LCC DA300 .B83 2020 (print) | LCC DA300 (ebook) | DDC 942.05–dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019024983

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019024984

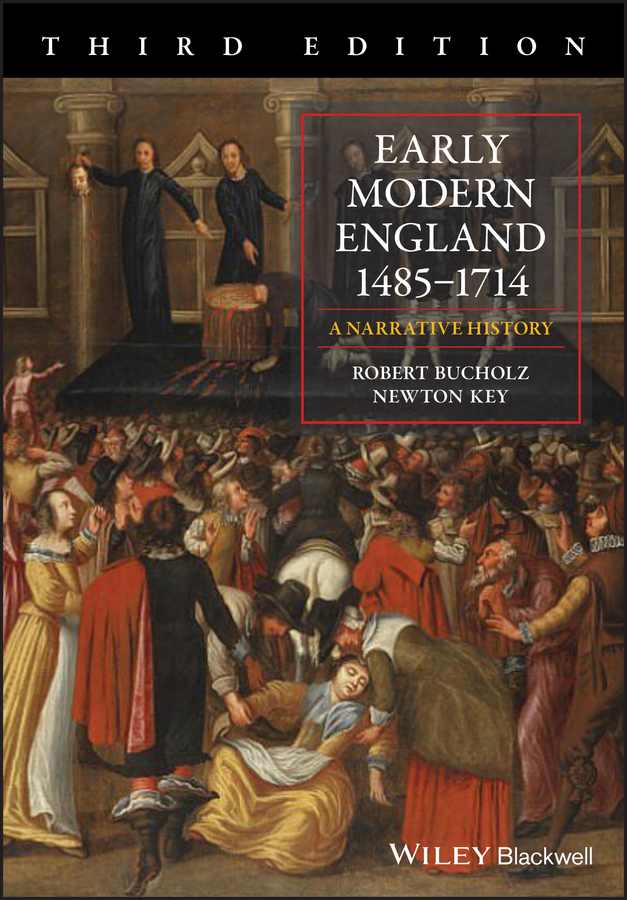

Cover Design: Wiley

Cover Image: The Execution of Charles I of England © The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

| I.1 | Diagram of an English manor |

| 1.1 | Henry VII, painted terracotta bust, by Pietro Torrigiano |

| 1.2 | Henry VIII, after Hans Holbein the Younger. Board of the National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside |

| 2.1 | Diagram of the interior of a church before and after the Reformation |

| 3.1 | Mary I |

| 3.2 | J. Foxe, Acts and Monuments title page, 1641 edition |

| 4.1 | Elizabeth I (The Ditchley Portrait) |

| 5.1 | First Encounter Between the English and Spanish Fleets, from J. Pine, The Tapestry Hangings of the House of Lords Representing the Several Engagements Between the English and Spanish Fleets, 1739 |

| 6.1 | Hatfield House, south prospect, by Thomas Sadler, 1700. The diagram shows the plan of the first (in American parlance, the second) floor |

| 6.2 | Tudor farmhouse at Ystradfaelog, Llanwnnog, Montgomeryshire (photo and ground‐plan) |

| 6.3 | Visscher's panorama of London, 1616 (detail) |

| 6.4 | A view of Westminster, by Hollar |

| 7.1 | James I, by van Somer |

| 7.2 | George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham |

| 7.3 | Charles I, by Van Dyck |

| 8.1 | The execution of Charles I |

| 8.2 | Oliver Cromwell, by Robert Walker, 1649 |

| 8.3 | Charles II's Coronation Procession, 1661, by John Ogilby, The Entertainment of His Most Excellent Majestie Charles II, in His Passage through the City of London to His Coronation (London, 1662) |

| 9.1 | Charles II as Patron of the Royal Society, by Laroon |

| 9.2 | James II, by unknown artist |

| 9.3 | Mary of Modena in Childbed |

| 9.4 | Presentation of the Crown to William III and Mary II |

| 10.1 | Queen Anne, by Edmund Lilly |

| 10.2 | The battle of Blenheim |

| 10.3 | Attack on Burgess's Meeting House after the trial of Dr. Sacheverell |

| C.1 | Castle Howard, engraving |

| I.1 | The British Isles (physical) today |

| I.2 | The counties of England and Wales before 1972 |

| I.3 | Towns and trade |

| 1.1 | The Wars of the Roses, 1455–85 |

| 1.2 | Southern England and western France during the later Middle Ages |

| 1.3 | Europe ca. 1560 |

| 2.1 | Early modern Ireland |

| 4.1 | Spanish possessions in Europe and the Americas |

| 5.1 | War in Europe, 1585–1604 |

| 6.1 | London ca. 1600 |

| 8.1 | The Bishops’ Wars and Civil Wars, 1637–60 |

| 9.1 | Western Europe in the age of Louis XIV |

| 10.1 | The War of the Spanish Succession, 1702–14 |

| 10.2 | The Atlantic world after the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713 |

We are deeply grateful to have been asked to prepare a third edition of Early Modern England 1485–1714: A Narrative History some fifteen years after the first copies of this work were printed. This is, of course, a business decision on the part of the publisher, but it would not have been made if teachers and their students had not been so generous to its two predecessors. In many cases, it has been those very teachers and students, including (we are proud to write) students of ours, who have identified errors that somehow made it into the first two editions. We are very pleased to have the opportunity to correct those errors in the pages that follow.

But the primary intellectual impetus for a third edition is, of course, the cornucopia of exciting, recent work in British history produced by our colleagues across the globe. As we readily admit, we are not experts in the entirety of English and Welsh, Irish, and Scottish history across this whole period. No one is. So we continue to rely on the works of specialists in the eras or areas in which we have not done original work to advance our knowledge and fine tune our narrative. (You will find many of these specialist works mentioned in our notes and our bibliography.) We have, in fact, been slower about putting out new editions than publishing accountants might wish, in large part because we wanted to wait until the weight of new monographs (the academic term for precise and sourced book‐length studies on a specific subject) required us to modify our narrative in a significant way. Our organizing principles (a synchronic look at English culture and society at three points of time, that is ca. 1450, 1600, and 1700, and a diachronic, that is more chronological, story from before 1450 until after 1714) remain as they were, and our more thematic organizing principles, such as the fate of the Great Chain of Being across the period, have continued to bear fruit. That said, new work on people of color and other nonnative people in England, on women, on climate and the environment, on Reformation cultures, and on some details of the political narrative, have obliged us to rework the story at several points. In particular, these pages show more agency on the part of women and ordinary people generally, both in their daily lives and in the great epoch of “England's Troubles” in the mid‐seventeenth century.

We might add a word about our choice of “early modern” in the title. Medieval and Modern have often been saddled with judgments and connotations that had more to do with our own current prejudices than with the period being so described. To people of a progressive bent, “medieval” equaled “backward” or simply “wrong”; “modern” was, well, “progressive” or, worse, “correct.” But more recently, others have judged modernity to be environmentally wasteful or “hegemonic”; and found in the medieval a harmonious stability. Our use of “early modern” – a term never used by anyone in the early modern period, of course – is in one sense a matter of convenience. Other terms, such as Renaissance, or Reformation, or Tudor‐Stuart, tend to privilege the cultural, religious, or political story. The early modern, in this sense, allows us to frame our story with changes in English society from the mid‐fifteenth to the mid‐eighteenth centuries. But we adopt the term “early modern” to mean something more than a neutral, chronological period. We would argue for, and hope to demonstrate in this book, a coherence to the period. If you understand the issues and interlocking factors affecting the English polity and the people at the end of the Wars of the Roses, you will be in a good position to understand the salient issues and factors at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession over two hundred years later. Indeed, it is the argument of this book that the latter were, to a great extent, the final working out of the former. Admittedly, the end of the fifteenth century is more early than modern, whereas the beginning of the eighteenth is more modern than early. All of which is to note that historians pay attention to time and place, and if we argue over periodization, it is only because we are trying to get it right.

In the preface to the second edition, we argued further that understanding the issues and interlocking factors affecting the polity and the people of early modern England as a whole is both helpful and necessary to a proper understanding of the issues affecting people in the Anglophone and Western world today. As we put the finishing touches to this third edition, it is clear to us that the troubles and controversies English people confronted and survived in this period are more relevant than ever. As of the date of this writing, on our side of the Atlantic, Americans are still debating whether the chief executive of the country is above the law; the degree to which religion qualifies or disqualifies one for citizenship and residence; the integrity of the courts; the proper relationship among men, women, and power; and the degree to which the nation should entangle itself in foreign commitments. This last question is even more pressing on the other side of the Atlantic, in the debates about Brexit. Those debates raise not only the question of Britain's relationship to Europe but also the proper interrelationships among the English, Scots, Irish, Welsh and of each of those people to the continent across the Channel. We did not, of course, write this book to be a primer on modern politics, but living simultaneously in the now and with its story for the whole of our professional lives, we are more convinced than ever that the people of the early modern British Isles achieved answers to these questions that continue to have relevance today. They fought and died for limited and democratic government, religious toleration, courts free from political influence, equality of opportunity, and that all four nations were integral to a Great Britain. By the time our book closes, they had also demonstrated that Britain had a vital role – diplomatic, military, economic, and cultural – to play in Europe. To reject any of these answers is to repudiate the legacy for which the people of early modern England lived, fought and died.

Admittedly, the story of early modern England provides countless examples of powerful personalities in sensitive roles who changed the narrative for everyone else. But, in the end, that history also proves that law, custom, and institutions matter even more by setting limits, preserving traditions, and providing the arenas and means by which the people so affected can push back. None of this is to say that early modern English or British solutions are an infallible guide to the future or what we ought to do next. As of this writing in the United States, a new Congress has been elected with a hope and fervor reminiscent of the Long Parliament returned in 1640. Like that body, it claims a mandate to try to thwart or limit the program of a powerful personality who has, himself the support of a large segment of the political nation. Some pundits, glancing back at the historical parallels, have begun to ask if a nation so divided can continue to function. Fortunately, History never repeats itself exactly: none of this is to say that things will turn out as they did before. But in trying to ensure that they do not do so, leaders on both sides of the Atlantic would do well to study the lessons contained in the following pages.

The appearance of a second edition of Early Modern England is most welcome to its authors, not least because it allows them to correct the errors which inevitably crept into the first. The opportunity of a “do‐over” is also a chance to bring the narrative up to date by incorporating exciting new material on the period that has come out since the first edition, not to mention older material that we had neglected previously. (The companion volume, Sources and Debates, has also been extensively revised in its second edition.) In particular, the authors have attempted to take into account recent Tudor historiography and strengthen those sections that address Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. We have also become more conscious of the continental and Atlantic dimensions of this story and have adjusted accordingly. We have added a section on the historiography of women and gender, modifying our presentation of women's lives in light of a more nuanced history of gender, which sees the story of men and women as more intermingled, and which gives early modern women agency rather than pities them as perennial victims.

At the same time, your faithful authors have resisted the temptation to make of this story something that it is not: a history of the British Isles, the Atlantic world, of Europe as a whole, or even a transnational story of a very mobile people. We are deeply aware and appreciative of new historiographical currents that view England and the English within each of these four contexts. We have made a conscious effort to take account of those contexts, and to strengthen them for this edition. But we have not attempted to tell a trans‐British Isles, Atlantic, Britain‐in‐Europe, or migrants story precisely because these are, in fact, many stories, the narrative threads of which inevitably become tangled and broken if contained within a single book. Indeed, Welsh and Irish historians have recently reacted with some skepticism to an all‐embracing “three kingdoms” British Isles approach. Thus, we stand by our initial position that an English narrative retains a coherence that such wider perspectives lack and that that narrative is of particular importance for the Western and Anglophone world. This last conviction has only been strengthened by the experience of the last few years, which have seen serious debates on our side of the Atlantic over the rights of habeas corpus and freedom from unreasonable search and seizure, the parliamentary power of the purse, the role of religion in public life, and whether or not the ruler can declare himself above the law in a time of national emergency. These were themes well known to early modern English men and women. They remain utterly – even alarmingly – relevant to their political, social, and cultural heirs on both sides of the Atlantic.

Which brings us to a final word about the audience for this book. When we first undertook to write it, we set out self‐consciously to provide a volume that would tell England's story to our fellow countrymen and women in ways that would be most accessible to them. That implied a willingness to explain what an expert or a native Briton might take for granted and to do so in a language accessible to the twenty‐first‐century student. Since its initial publication, Early Modern England has had some success on both sides of the Atlantic, not least, it turns out, because, as the early modern period recedes from secondary training in history in Great Britain, the twenty‐first‐century British student cannot be assumed any longer to have become familiar with – or jaded by – this story. And so, as we have undertaken this revision, we have tried to become more sensitive to its potential British, as well as Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, and other Anglophone readers, while retaining the peculiar charms of the American vernacular. It is in the spirit of transatlantic and global understanding and cooperation that we welcome all our readers from the Anglophone world to a story that forms the bedrock of their shared heritage.

The authors of this book recall, quite vividly, their first exposure to English history. If you are like us, you first came to this subject because contemporary elite and popular culture are full of references to it. Perhaps your imagination has been captured by a classic play or novel set in the English past (Richard III, A Man for All Seasons, Journal of the Plague Year, Lorna Doone), or by some Hollywood epic that uses English history as its frame (Braveheart, Elizabeth, Shakespeare in Love, Restoration, The Patriot). Perhaps you have traveled in England, or can trace your roots to an English family tree (or to ancestors whose relationship to the English was less than happy). Perhaps you have sensed – rightly – that poets and playwrights, Hollywood and tour books have not given you the whole story. Perhaps you want to know more.

In writing this book, we have tried to recall what we knew and what we did not know about England when we first began to study it as undergraduates. We have also tried to use what we have learned over the years from teaching its history to (mostly) our fellow North Americans in a variety of institutions – Ivy League and extension, state and private, secular and sectarian. Thus, we have tried to explain concepts that might be quite familiar to a native of England, and have become familiar to us, but that may, at first, make little sense to you. To help you make your way through early modern England we have begun with a description of the country as it existed in 1485 and included several maps of it and its neighbors. We have highlighted arcane contemporary words and historical terminology in bold on their first use and tried to explain their meaning in a Glossary. We urge you to use these as you would use maps and language phrase books to negotiate any foreign land. When we introduce for the first time a native of early modern England, we give his or her birth and death dates, where known. In the case of kings and queens, we also give the years they reigned. We do this because knowing when someone came of age (or, if he was a Tudor politician, whether or not he managed to survive Henry VIII!) should give you a better idea of what events and ideas might have shaped his or her motivations, decisions, and destiny. Thinking about historical characters as real people faced with real choices, fighting real battles, and living through real events should help you to make sense of the connections we make below and, we hope, to see other connections and distinctions on your own.

The following text is, for the most part, a narrative, with analytical chapters at strategic points to present information from those subfields (geography, topography, social, economic, and cultural history) in which many of the most recent advances have been made, but for which a narrative is inappropriate. That narrative largely tells a story of English politics, the relations between rulers and ruled, in the Tudor period (1485–1603, Chapters 1–5) and the Stuart period (1603–1714, Chapters 7–10). Chapter 1 includes a brief narrative of the immediate background to the accession of the Tudors in 1485, the Conclusion, a few pages on the aftermath of Stuart rule from 1714. We believe, and hope to demonstrate, that the political developments of the Tudor–Stuart period have meaning and relevance to all inhabitants of the modern world, but especially to Americans. We also believe that a narrative of those developments provides a coherent and convenient device for student learning and recollection. Finally, because we also think that the economic, social, cultural, religious, and intellectual lives of English men and women are just as important a part of their story as the politics of the period, we will remind you frequently that the history of England is not simply the story of the English monarchy or its relations with Parliament. It is also the story of every man, woman or child who lived, loved, fought, and died in England during the period covered by this book. Therefore, we will stop the narrative to encounter those lives at three points: ca. 1485 (Introduction), 1603 (Chapter 6), and 1714 (Conclusion).

In order to provide a text that is both reader friendly and interesting, we have tried to deliver it in prose that is clear and, where the material lends itself, not entirely lacking in drama or humor (with what success you, the readers, will judge). In particular, we have tried to provide accurate but compelling accounts of the great “set pieces” of the period; quotations that will stand the test of memory; and examples that enliven as well as inform while avoiding as much as possible the sort of jargon and minutiae that can sometimes put off otherwise enthusiastic readers. Again, this is all part of a conscious pedagogical strategy born of our experience in the classroom.

That experience has also caused us to realize the importance of “doing history”: of students and readers discovering the richness of early modern England for themselves through contemporary sources; making their own arguments about the past based on interpreting those sources; and, thus, becoming historians (if only for a semester). For that reason, we have also assembled and written a companion to this book titled Sources and Debates in English History, 1485–1714 (also published by Blackwell). The preface to that book indicates how its specific chapters relate to chapters in this one (see also chapter notes at the end of this book).

A word about our title and focus. One might ask why we called our book Early Modern England, rather than Early Modern Britain? After all, one of the most useful recent trends in history has been to remind us that at least four distinct peoples share the British Isles and that the English “story” cannot be told in isolation from those of the Irish, the Scots, and the Welsh. (Not to mention continental Europeans, North Americans, Africans, and, toward the end of the story, Asians as well.) We agree. For that reason the text contains significant sections on English involvement with each of the Celtic peoples (as well as some discussion of England's relationship to the other groups noted above) in the early modern period, all of which are vital for our overall argument. But we believe that it is the English story that will be of most relevance to Americans at the beginning of the twenty‐first century. We believe this, in part, because it was most relevant to who Americans were at the beginning of their own story, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. We would argue, further, that English notions of right and proper behavior, rights and responsibilities, remain central to national discourse in both Canada and the United States today. Important as have been the cultural inheritance of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales to Americans, the impetus for the inhabitants of each of these countries to cross the Atlantic was always English, albeit often oppressive. Moreover, brutal and exploitative as actual English behavior has often been toward these peoples, the ideals of representative government, rule of law, freedom of the press, religious toleration, even a measure of social mobility, meritocracy, and racial and gender equality, which some early modern English men and women fought for and which the nation as a whole slowly (and often partially) came to embrace, are arguably the most important legacy to us of any European culture.

Finally, as in our own classes, we look forward to your feedback. What (if anything!) did you enjoy? What made no sense? Where did we go on too long? Where did we tell you too little? Please feel free to let us know at earlymodernengland@yahoo.com. In the meantime, there is an old, wry saying about the experience of “living in interesting times.” As you will soon see, the men and women of early modern England lived in very interesting times. As a result, exploring their experience may sometimes be arduous, but we anticipate that it will never be dull.

No one writes a work of synthesis without contracting a great debt to the many scholars who have labored on monographs and other works. The authors are no exception; our bibliography and notes point to some of the many historians who have become our reliable friends in print if not necessarily in person. We would also like to acknowledge with thanks our own teachers (particularly Dan Baugh, the late G. V. Bennett, Colin Brooks, P. G. M. Dickson, Clive Holmes, Michael MacDonald, Alan Macfarlane, the late Frederick Marcham, and David Underdown), our colleagues, and our students (whose questions over the years have spurred us to a greater clarity than we would have achieved on our own). A special debt is owed to the anonymous readers for the press, whose care to save us from our own errors is much appreciated – even in the few cases where we have chosen to persist in them. We have also benefited greatly from our attendance at seminars and conferences, most notably the Midwest Conference on British Studies, and from hearing papers given by, among others, Lee Beier, David Cressy, Ethan Shagan, Hilda Smith and Retha Warnicke. For advice, assistance, and comment on specific points, we would like to thank Andrew Barclay, the late Fr. Robert Bireley, SJ, Barrett Beer, Mary Boyd, Regina Buccola, Jeffrey Bucholz, Eric Carlson, Erin Crawley, Brendan Daly, Jared Donisvitch, John Donoghue, the late Carolyn Edie, Gary DeKrey, David Dennis, Erin Feichtinger, Mark Fissel, Alan Gitelson, Bridget Godwin, Michael Graham, Jo Hays, Roz Hays, Caroline Hibbard, Iain Hoy, Peter C. Jackson, Theodore Karamanski, Carole Levin, Kathleen Manning, Sarah McCanna, the late Gerard McDonald, Eileen McMahon, Marcy Millar, Paul Monod, Philip Morgan, Matthew Peebles, Jeannette Pierce, James Rosenheim, Barbara Rosenwein, James Sack, Lesley Skousen, Johann Sommerville, Robert Tittler, Joe Ward, the late Patrick Woodland, Mike Young, Melinda Zook, and the members of H‐Albion. We are grateful for the support, advice, and efficiency of Tessa Harvey, Brigitte Lee, Angela Cohen, Janey Fisher, Sakthivel Kandaswamy, and all the staff at Wiley‐Blackwell. We have also received valuable feedback from students across the country and, in particular at Dominican University, Eastern Illinois University, Loyola University, the University of Nebraska, and the Newberry Library Undergraduate Seminar. Our immediate family members have been particularly patient and accommodating. We would especially like to thank Laurie Bucholz and Dagni Bredesen for keeping this marriage (not Bob and Laurie or Newton and Dagni but Bob and Newton) together. For this, and much more besides, we thank them all.

| Citations | Spelling and punctuation modernized for early modern quotations, except in titles cited. |

| Currency | Though we refer mainly to pounds and shillings in the text, English currency included guineas (one pound and one shilling) and pennies (12 pence made one shilling). One pound (£) = 20 shillings (s.) = 240 pence (d.). |

| Dates | Throughout the early modern period the English were still using the Julian calendar, which was 10–11 days behind the more accurate Gregorian calendar in use on the continent from 1582. The British would not adopt the Gregorian calendar until the middle of the eighteenth century. Further, the year began on 25 March. We give dates according to the Julian calendar, but assume the year to begin on 1 January. Where possible, we provide the birth and death dates of individuals when first mentioned in the text. In the case of monarchs, we also provide regnal dates for their first mention as monarchs. |

| BCE | Before the common era (equivalent to the older and now viewed as more narrowly ethnocentric designation BC, i.e. Before Christ). |

| BL | British Library. |

| CE | Common era (equivalent to AD). |

| Fr | Father (Catholic priest). |

| JP | Justice of the peace (see Glossary). |

| MP | Member of Parliament, usually members of the House of Commons. |