Pinedo Kahlo, Isolda

Intimate Frida / Isolda Pinedo Kahlo; translator Jacques Sagot; philological revisions Thomas Littman, Nathan Mulholland. —Bogotá: Dipon Publications; Buenos Aires: Gato Azul Publications, 2005; Cangrejo Publishers, 2006.

304 p.

Original Title; Frida íntima.

1. Kahlo, Frida, 1910–1954 2. Mexican painters – Biographies 3. Kahlo, Frida, 1910–1954– Photographs I. Sagot, Jacques, tr.

II. Littman, Thomas; Mulholland, Nathan; rev. III. Tit.

927 cd 30 ed.

AJF3437

CEP-Bank of the Republic-Library Luis-Angel Arango

First Edition, June 2006

© Isolda P. Kahlo, 2004

© Ediciones Dipon, 2005

© Cangrejo Publishers, 2006

E-mail: cangrejoedit@yahoo.com

Bogotá, Colombia

© Gato Azul Publications

E-mail: edicionesgatoazul@yahoo.com.ar

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Editorial preparation:

Dipon Editions and Distributions

Cover design:

Innova Advertising & Graphic Design

Digital printing:

Grupo C. Service & Design

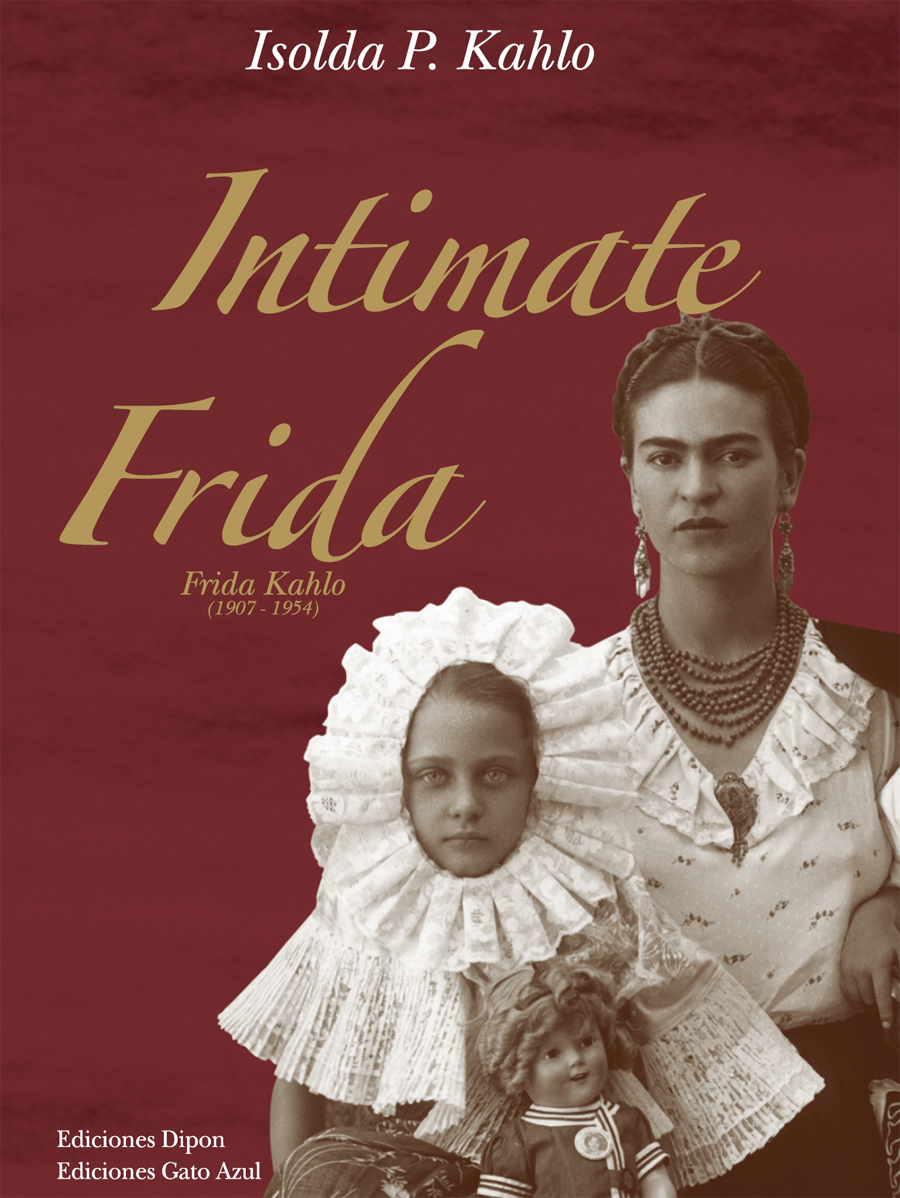

Cover photograph:

Frida and Isolda dressed in Tehuana clothing

Translator:

Jacques Sagot

Philological revisions:

Thomas Littman, Nathan Mulholland.

Diagrams:

María Cristina Galindo Roldán

Distributors:

International Becan S.A. of C.V.

E-mail: interbecan@yahoo.com.mx

Dipon Editions and Distributions

E-mail: dipon@andinet.com

Telefax: (571) 2529694 - 4344139

ISBN: 978-958-553214-4

The text, the assertions made, and the photos in the book are the exclusive responsibility of the authors. Neither the editors, the printers, the distributors, nor the booksellers have any responsibility for what is written in this book.

The rights of the author of this book have been patented by agreement with the International Act of Rights Over Patents and Projects of 1998 in numbers 77 and 78.

All of the rights of the text, photographs, and the reproduction of the original work of the private collection on cloth that accompanies this book are reserved. No one may publish in part or in whole content like the graphic material of this work.

Neither may anyone use any system of reproduction or transmission in any electronic media, digital or photocopied, without the written permission of the publishers.

Diseño epub:

Hipertexto – Netizen Digital Solutions

PREFACE

LETTER TO ISOLDA

LETTER TO FRIDA

I.CHILDHOOD AND FIRST MEMORIES

Experiences will scar you

Close relatives

Cohabiting with genius

Loneliness and company

Children between two worlds

From the little house to the store

To grow up in a different world

Frida, the suffering?

“Laugh at death”

II.FRIDA’S ORIGINS

First official photographer of Porfirio Díaz

Presentiments that come true

A very special son-in-law

III.MY MOTHER CRISTINA

“A few little stings”

Exposing life

The art of being Kahlo

The farm

Another school: the daily effort

Care given to Frida during her last months

Between disbelief and trust

The tree, the trunk, the branches

Unfulfilled mothers

Between the cross and the political meeting

Living together and family union

To respect without conceding

IV.MY AUNT FRIDA

Loves and men

“By my own right”

Illness

Hospital

Tastes and gender

Accident and destiny

Houses and portraits

V.MY UNCLE DIEGO

Facing history

“I cannot love him for what he is not”

Artist and politician

“The Bull” (Diego’s nickname in Europe)

The animals

Political refugees

VI.“THE FRIDOS ON THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF MASTER FRIDA KAHLO’S DEATH”

Ambiance in the Blue House

Clarifications by Rina Lazo

Getting to meet Frida and Rivera

Last months

Diego, the passionate

Frida, the love

VII.THE DEPARTURE

“Life is a big mess”

“The best kept secret”

GENEALOGICAL TREE

GALLERY OF PHOTOGRAPHS AND DOCUMENTS

CHRONOLOGY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

To Alberto Garduño

Because without his unconditional and lasting support, this book would have been impossible.

To Mara Romeo

For her constant presence. For being the engine and the motivation behind the materialization of this project.

To my editors

Who were willing to assume this challenge, especially Leyla Cangrejo, for her passion and professionalism.

A tradition rooted in the mythology of romanticism and its conception of the artist as a cultural hero would want to believe that everything pertaining to the life of a genius has to bear the mark of the sublime. Everything in their lives –gestures, decisions, personality traits, eccentricities, even the most dissonant mistakes– are thus transformed into esthetic substance. We would want their lives to be masterworks, a perfect coherence and continuity between the work and its creator. Roland Barthes has criticized this conception as a basically bourgeois aberration – the perennial realism of the bourgeois culture, its need to identify the signified with the signifier. And then we learn about the real human dimension of these heroes– their pettiness, narcissism, avariciousness, arbitrariness, and childishness, all of which are no more than their human specificity. We are scandalized; either the work or the figure lies. A harmonious painting, a novel or masterful symphony cannot possibly be the product of a person capable of such spiritual smallness. Then we are left with two choices—to dismiss the work as an essentially hypocritical utterance, or to disqualify the creator as the accidental author of some work that happened to be marvelous but was simply by virtue of a great skill, not supported by an equally admirable human quality.

It is difficult to read a book of memoirs as intimate as this one without laughing or being profoundly irritated by the caricature-like behavior of, say, Diego Rivera. He was a storm to all who surrounded him, and a really devastating one. And yet, he is redeemed by the love of Frida, a love so lofty that it could absolve him from all his human flaws. Stendhal once said that love was a phenomenon of crystallization, not unlike what happens in the salt mines of Salzburg; if one throws in the grottos a laurel branch, after a few days it will reappear covered by the most beautiful crystalline configurations. What Stendhal meant with this suggestive metaphor is that love is in the eye of the beholder. Love is an inherently creative feeling; it somehow invents and ornaments the tree it chooses to nest in. This unilateral conception of love, however, is, to say the least, inaccurate. Love, like the esthetic experience, is an act of co-creation. The laurel branch thrown into the mine has to have, after all, some intrinsic merit to be covered by the iridescent stalactites that represent, in Stendhal’s allegory, the beholder’s delusive creation around the figure of the loved one. Love is a projection, yes, but also a form of superior lucidity that allows us to see in someone the beauty that went unnoticed by others.

This is, above all, a book about love. A love story written with love in the form of reminiscences of evocations that gives us a profoundly human image of Frida and Diego. It dispels a number of tabloid misconceptions, some inspired by enviousness or sheer meanness that have always surrounded the life of this famous couple – a confluence of genius of a kind that is rare if not unique in the history of art. Isolda Pinedo Kahlo, the niece of Frida, speaks with infinite reverence and devotion about her aunt and uncle, although at moments one may question whether Diego deserves to be remembered that way. Everything in their lives seems to acquire a titanic, bigger than life intensity – the love they professed for each other, the way they emotionally wounded each other, the sincerity of their forgiveness, their fierce activism in concrete political causes, their love for the Mexican people… it all happens on a scale that comes close to the “hybris,” the sin of excess that the Greek gods punished in figures such as Icarus or Prometheus.

Above all, it is Frida’s uncanny love for life that makes this book such a profoundly moving experience. To say that she was a fighter would be the understatement of the century. The amount of pain she had to endure is simply overwhelming. Her suffering attains the level of martyrdom. Her love of life and her love of painting were indiscernible; she lived to paint and she painted to live. Literally, painting had for Frida the same meaning Sheherezade’s improvised stories had for her—they were a way of deferring death, an exorcism, a daily creative struggle to postpone the inexorable visit of “that one who will certainly not miss the ‘rendez-vous,’” as the poet Antonio Machado once said. Frida created with her paintings a magic circle around her, a ring of beauty that death had great difficulty trespassing. Her heroism is nothing more than a byproduct of her love of art. She clung to life in a way that establishes an inevitable parallelism with Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin Nerval, Van Gogh, Camille Claudel; they all found in their art a way of battling against obscure and menacing forces, be it deafness, insanity, sickness or exile.

Isolda Pinedo Kahlo is the last descendant of the Kahlo dynasty. Her testimony has not only an enormous documental value, it dispels a Hollywoodish image of Frida that distorts or exaggerates with its usual crassness the facts of her life. It also unveils some scrupulously kept secrets, disturbing truths well hidden in the family’s “sanctasanctórum”. To pass judgment on Diego Rivera would be easy, and in fact many readers will do so rather hastily, especially considering the facts concerning his compulsive cheating, the legal maneuvering he apparently perpetrated to exclude Cristina Kahlo, Frida’s devoted sister, from her will, and most chillingly, his possible active role in his wife’s death, no doubt dictated by love and compassion for her unbearable and “pointless” torment. It is not so much the intensity of the suffering, but its “pointless,” absurd, meaningless nature that motivated his action of euthanasia. What could be more typically human? We can bear the greatest pain in the world… as long as it has a sense and a direction, what the Greeks would have called a “telos.” But it had none for the belligerent atheist that was Diego. We are in the presence of a man who could not bear the apparent meaninglessness of suffering, and he acted coherently with his radical, skeptical nature.

Some of the testimony’s images are haunting: Frida already amputated of a leg, lying on the floor and desperately painting her canvasses with her fingers and knuckles; Diego, that giant of a man, always armed with a pistol, crying like a baby at the side of her lifeless body; Frida hanging from two metal rings in order to keep a vertical position that would somehow allow her to paint… Even death itself respects such power of will, such bravery, such vital desire. I translated these memoirs with tears in my eyes, with trepidation of the soul, and the profound conviction of perpetuating a memory that has to be recalled for all those who have given up hope, who have let Thanatos prevail over Eros.

And yet, in Isolda’s memories, Frida emerges as a cheerful, optimistic person, someone who certainly would not have wanted to be remembered for her suffering, but rather for her love of life. The fact is that both have become inseparable, dialectic truths. Such magnitude of pain could have only been overcome with a correlative magnitude of “élan vital,” as Bergson would have said. Frida’s work illustrates beautifully the founding image behind Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du Mal”— those flowers which ascend vertically toward the light, but are engendered by the putrefaction generated by myriads of bacteria in the pestilence of the swamp. Frida was an alchemist – life gave her pain, and she transformed it into beauty. She is the incarnation of a concept pertaining to biology but also applicable by analogy to the life of the spirit – Goodwin and Varela’s notion of “autopoiesis,” that is, the process by which an organism is capable of regenerating, reproducing and healing itself. Aautopoiesis would mean here, literally, self-creation. The plants which have the ability to transform carbon dioxide into breathable gases are the paradigm of this concept. When Baudelaire said, “Paris, filthy city, you gave me your mud, I transformed it into gold!” he was proclaiming the triumph of autopoiesis. His experience is not far from Beethoven, Schumann, Van Gogh or Frida’s alchemy. Considered as such, she can by no means be termed a simple, tragic figure. Her whole life is a triumph of self-healing through art, a model of autopoiesis as a transforming force.

That is the way she undoubtedly would like to be remembered. That is the way Isolda evokes her and brings her back to life through that magic process, that form of resurrection that is the reminiscence.

Jacques Sagot

Houston, Texas

November, 2005

The story narrated in this book is a new perspective that in many ways modifies other subjective testimonies and research documents pertaining to the fascinating figure of Frida Kahlo. In all fairness, we all know that there is no such thing as a unique truth or universal criteria for judging a historical figure. However, a granddaughter will eventually tire of seeing the tears running down her grandmother’s face, a grandmother who still cannot find in so many books published to date the true face of that Frida whom she intimately met and loved, the Frida with whom she lived and shared such a substantial part of her life.

The memories that Isolda treasured were evoked and described from her intimacy. They are inevitably permeated with the tragedy of Frida’s multifarious suffering, especially the excruciating physical pain provoked by the many surgeries to which she was exposed. This is an objective fact.

My grandmother had the opportunity to see her laugh, sing, and play, and even dance with her. At that young age, Isolda cherished dancing above all else.

She walked through that labyrinth called Frida Kahlo, illuminated by her own heart. While unburying the emotions and fears of her childhood, she succeeded in bringing back to life that candor that operates as a mirror, a mirror by which the older person she had become could find her true being.

Opening the old boxes and wardrobes of her heart and mind indeed took a long time and considerable patience. With this book she has finally managed to leave us a vivid testimony about the other Frida, a Frida as true as all her masks. This story is told by a woman who was tenderly loved by Frida, and in return, she was sincerely devoted to her aunt.

With all my love for you, Abi Isolda.

Thank you for your past, your experiences, and the legacy Frida left you. You have forged my present and my future with your memories.

Your granddaughter, Mara De Anda

Mexico, July 2004

July 13, 2004

Dearest Aunt Frida:

Today we commemorate half a century since you left us. You were forty-seven years old then; now I am seventy-five. Strangely, however, I continue to see you as my elder; you are still and always will be my second mother. I was the girl who once came to you hand in hand with my brother Toño1 and my mother Cristina, your younger sister. I was the girl who came to live with you and my Uncle Diego in the Blue House of Coyoacán.

In that magical home I grew up with you, my family. There I spent many years of my life, from my childhood until my marriage. These were intense, joyful, and eventful years. There I first met the blissfulness of family life and the joy of love. There I dreamt, laughed, danced, experienced merriments and fears, and lived through economic ups and downs; there I grew from a child to a woman; and there, too, I fell in love many times. It was there in your home that I went through all the stages of what may be called a normal life. Alas! Dear Aunt Frida, today I can, with all sincerity, speak to your shadow and to myself, and say that among you all I was happy, very happy indeed.

And although I learned many things in the Blue House, it was your example that made me understand the fact that certain people may be touched by the fortune (or the curse) of becoming famous without ever losing their basic human nature. Fame is nothing but a peculiar form of oblivion, which cannot be completely consummated until someone is loving enough to act as the custodian of those images that remain engraved in the memory. In your case Aunt Frida, I happen to hold those last memories; and I am the custodian to collect them; I am the last person on earth of the many who lived near you, who danced with you, who listened to your advice (as well as your occasional reprimands), who held their hands within yours, who witnessed your happiness and your suffering, who knew about your hopes and disillusions, who saw you shine during many years with dazzling splendor and then wither in an inexorable finale that for me was certainly more of a serene pact with la Pelona2 (as you used to call her) than an earth shattering loss.

I do understand why history, mummifying as usual all great figures who once symbolized life, has constrained you with the hideous ligatures of celebrity and all sorts of difficult issues (physical as well as mental, social, and political ones). I understand history’s haste to bury you under mountains of words and laudatory critiques—sharp, deeply analytical, explanatory, exaggerated in praise as well as hatred, falsified, utterly stupid and tactless commentaries, and often ill-intentioned. I understand that all this may have transformed your flesh into marble, your skin into bronze, and your passions into a simple narrative topic. I guess such a process is inevitable in a person as eminent as you. In the long run, all celebrities end up becoming salt statues, or perhaps wax figures, as those who live in a popular Manhattan museum (a place that so many times served you as a refuge), a museum now ornamented with a little plaque bearing your name. And yet, that is not you, but actress Salma Hayek personifying you. Yes, I concur in thinking that Salma Hayek is indeed your new great friend on the screen, just as Ofelia Medina reincarnated you with remarkable dignity many years ago (and her physical personification was, if anything, even more impressive and true to life than Hayek’s). I also believe that she will accompany you through that mysterious path where identities modify one another in unpredictable ways. However, let me point out that you and I both know you would have doubtlessly preferred papier-maché instead of wax.

Every person who becomes a celebrity has the risk of coagulating in the cold like gelatin, so I am no longer surprised or alarmed by all this. At this point of my life and your fame, I am no longer sure of my belief in a unique truth, a truth that presides over everything that is human. Maybe the different stories contained in those many books written about you, often uneven and discordant, are all to a certain degree true, although the vast majority may not be more than echoes of echoes of echoes—and so on. Perhaps even the malignant lies carefully weaved around you, especially those emanating from twisted and dubious sources (such as Raquel Tibol) are also true in a way. But they are not my truths, and they seem utterly unimportant. I learned long ago that it is futile to discuss with lightning, with avalanches, with earthquakes, and with those forked tongues divided like your tormented spine.

I have stated in this book my truth about you, the truth that a child’s mind first, then a young spirit, has integrated profoundly into her intimate being the truth of a woman who knew how to love me as a second mother, sometimes as a sister, and always as a trustworthy friend. You were a “mother-sister” who lived passionately, tumultuously, and for decades defended herself from “La Tía de las Muchachas,” la Flaca, la Pelona.3 You became famous much in spite of yourself, I suspect.

For all that, this book can only be for you, my beloved Frida, aunt, mother, and sister of the girl I once was. This book is one that is essentially about you and me.

With the same deep affection I have always

professed for you,

Your niece,

Isolda

would not want my grandchildren, Mara, Diego, and Frida, who are now old enough to discern between good and evil and well trained to avoid all forms of negativity in life, to get acquainted with the intimate sense of my childhood experiences. On the other hand, it is also my aim that people who read this book understand who really was a part of their daily lives—Frida Kahlo, her close family, and her husband, muralist Diego Rivera.

would not want my grandchildren, Mara, Diego, and Frida, who are now old enough to discern between good and evil and well trained to avoid all forms of negativity in life, to get acquainted with the intimate sense of my childhood experiences. On the other hand, it is also my aim that people who read this book understand who really was a part of their daily lives—Frida Kahlo, her close family, and her husband, muralist Diego Rivera.

That is why I will now open the gates of my memory, even if this gesture may bring back some rather unpleasant memories. Life is a river of constantly flowing experiences, some of them pleasing, others unfortunate, with discoveries that are sometimes luminous, often times dark, with days of excitement, and days of dreadful boredom.

The spectator who connects for the first time with Frida’s paintings, some of which art critics have described as “martyrological,” may be overwhelmed by the image of an eternally suffering woman, a human being that did little else than cry like “La Dolorosa de Coyoacán.”4 (It may be no coincidence that her name, if preceded by the possessive pronoun “su” gives us the word “su-Frida” or “the suffering one.”) If we read her letters or her diary, we will find instead a spirit of mockery and provocation that has now become legendary. Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo did not spend her life sobbing; rather, most of the time she was singing or whistling joyful Mexican tunes, popular melodies, and little roguish songs. Whenever she would cry with sadness (many times she cried out of sheer laughter or happiness), she would do it furiously, in a direct and completely frank manner with that openness that characterized everything she did in life. Sentimental disappointments (whenever she split with Diego), health problems at home, or financial distress caused her to occasionally cry, but only if domestic budgetary problems were seriously upsetting her family, a close friend, a pupil of hers, or anybody who had a resident visa in her heart. Well, I have to accept that I did see her cry a couple of times, but that happened only in the most sacred intimacy and toward the end of her life, when physical pain was beginning to become unbearable for her. By then not even the morphine injections could mitigate the intensity of her suffering. On such occasions, she would look at me with great tenderness and warn me about the harmful effects of drugs on the human organism. “Look at me,” she would say with a sad smile on her face. “This is what drugs can do to a person. You must never try them.” And although I was aware that, in her case, it was the doctor and not the vice that prescribed such powerful substances, I have kept, even to this day an invincible repulsion toward all sorts of addictions.

Life with my aunt and uncle was far from what you would call a “normal existence” for children. Neither of them was endowed with passions, genius, or ingenuity that could be described as average. Ours was a home under the aura of a couple torn by stormy emotions, genius, and ingenuity that would manifest themselves in multiple, strong ways. For example, at home we were never told, “Do not listen to this, girl,” or “Get out of here, boy.” As a result of this upbringing, we were always in direct contact with all sorts of daily events. We must have acquired some wisdom out of this pedagogy of openness, because my brother and I both learned by osmosis how to answer the captious questions of strangers. We knew how to respond calmly in our own childish way to the interrogations of adults without ever letting them surprise us with their finesse or betraying some important family secret through the calculated extortion of the truth. There were many circumstances that had to remain secret within the walls of the three homes of my Uncle Diego and my Aunt Frida. Those homes were the center of reunion and even the political asylum of very important people in the history of Mexico and the world.

Frida and Diego with some of his assistants and friends standing by the mural of the Public Education Office, 1931

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera gave my brother Toño and me two priceless gifts that were to prove crucial in our human development. First, they loved us very much and made us feel the sincerity of that love constantly, through words as well as acts. Secondly, they never hid anything from us, which was, in general, a highly positive policy in our upbringing. I say “in general” because I must also confess that sometimes, from some indiscreet chink between the walls of the basement, my brother and I saw things that I will not mention now, but which doubtlessly should not have been seen by children our age, and which I would not want to see even now, for that matter. At any rate, I can now appreciate much better that ambiance of freedom and honesty that we had the privilege to enjoy. It never felt strange to us, since we never knew any other kind of environment.

Frida or Diego never made us feel alien in that house. In fact, we lived just as all Mexican families at the time, with the grandparents, uncles, aunts, and my mother Cristina, a situation that is rarely found in modern families. For my brother Antonio and me, our childhoods unfolded in what was then called “the big house.” The section of the garden where now lies the pyramid was bought by Diego when Trotsky came to Mexico, because the Russian revolutionary feared that the neighbor’s terrace could be used as a platform to launch an attack against him or his family. In other words, we occupied the part of the house that now hosts a shop and a small cafeteria. Long afterwards, my uncle had the pyramid built in the garden. I imagine that he must have used it as a support for some stone idols from the pre-Hernán Cortés era. He also built Anahuacalli, which years later became his greatest testimony of veneration for our ethnic roots. Even though Anahuacalli brought my uncle tremendous satisfaction, the unending expenses caused him a real headache. But with this work, he fulfilled his dream of leaving the people of Mexico a cultural and patrimonial milestone. This same ambition would lead him later to the donation of the house-workshops in San Ángel and the Blue House in Coyoacán.

Frida and Diego were not the only ones who gave us the feeling of a true home. Following their example, all the people in the artistic milieu that I had the fortune to meet during my childhood would address my brother and me with the respect and courtesy usually reserved only for adults. That is how I grew up accustomed to a daily human exchange with formidable figures whose intellectual stature my brother and I were incapable of measuring. Antonio and I had the opportunity to meet all sorts of people: kings, politicians, and above all, artists, lots of artists. That is why I learned at a very early age how to treat people, from the highest social position to the most humble. To me they were all equal. Most importantly, I held in immense value the indigenous people of Mexico. The trivialization of celebrities is a phenomenon that often happens to children who have lived in the proximity of big names. Eventually it may turn out to be a real blessing. In spite of all this, such blissful blindness to the paraphernalia of fame may not last long enough, and sometimes it does not prevent children from having to grow up under the unavoidable shadow of their illustrious parents. This shadow may have a crushing effect on their personalities. Our case was completely different. Diego and Frida were simple, unpretentious people, and we never saw in them the famous muralist or the controversial artist, even less so the revolutionaries that provoked scandals and inspired antagonistic passions. They simply were Aunt Frida and Uncle Diego, two people just like all the other people in the world.

The Blue House before its modification

Contrary to what the reader may assume, my vocabulary never developed in an extraordinarily rich way. I have what you may call a normal vocabulary, insufficient for expressing the special memories that I treasure and would like to narrate. I never cultivated any particular talent in oratory or eloquence, partly because everything I heard was already presented to me in a way that was hardly perfect, often times inflated by Diego’s well known tendency to exaggerate and blend facts with fantasy.

Whenever any “block” would come between my brain and the actual idea I was trying to express, or whenever I simply did not know the answer, my uncle or aunt would respond for me. If one of them was not particularly attentive at the moment, the other would come to my rescue, just like in the painting “The Little Deer,” where Frida portrays herself sporting a double ear.

Frida’s ever present sense of humor constantly radiated around her. In order to detect this, it was enough to sharpen one’s sight and remember that she was, after all, a being firmly rooted on the ground, a direct and realistic person, and honest even in the smallest details of her life, almost to the point of impudence. Diego was no less direct and realistic, but I can also think of many other adjectives that could describe him. In fact, if I had to define Frida as a person, I would do it with a minimum of words: loving, courageous, straightforward, spontaneous, and generous.

My most remote images from childhood go back to the time when my parents were still married. My father, Antonio Pinedo, was dashingly handsome, and as all good daughters will say, my mother seemed to me the most beautiful among the four Kahlo sisters. And maybe she was, although I would rather not express this kind of judgment, especially since there are so many portraits and pictures of my mother and my aunts that will give the reader a very accurate idea of what I just stated. A painting that I could mention as an example is Frida’s “The Bus,” finished in 1929, the same year that I was born. According to many critiques, the painting has a “deliciously primitive flavor.” It shows, among other characters, my mother, then twenty-one years old. From Diego’s paintings, my choice would be his mural “The World of Today and of Tomorrow,” where we can see my mother Cristina and my Aunt Frida.

My father’s second family name was Chambòn. (One has to pronounce it without excessively emphasizing the French accent, because it may make people laugh.) Contrary to what the word means in Spanish, he was not clumsy or unrefined. He was always surrounded by beautiful women, and often drunk as well. It was not without reason that my mother soon divorced him. My paternal grandmother and her family came from the lineage of an important textile entrepreneur who arrived in Mexico with Emperor Maximilian. My father and his brothers were the owners of “Pinedo Deportes”, a shop in Mexico City’s downtown area.

A strong feeling of mortification, of scruples and shyness (I do not know—perhaps all of this), dissuaded me from ever looking for my father after he left home. Besides, my mother did not allow me to go out with him whenever he would stop by our place, at times riding a horse. All I could do was wave at him from the balcony of my living room. The few times I remember having been near him reminded me of the smell of alcohol that would long remain after his farewell kiss. On the other hand, I often visited my brother Toño. Now I deplore the fact that I was never motivated to have a closer relationship with my father.

The Pinedo Kahlo family shortly before Antonio and Cristina’s separation

My parents met each other at a fair in the town of Coyoacán. My mother had been elected queen of the local pageant, and my father, being a charro,5 was passing by when he saw my mother. He instantly fell in love with her. After that he courted her unceasingly until she became his girlfriend. Finally they married and went to live in Churubusco, where I was born. Their separation was due to my father’s alcoholism and his addiction to women, two things that my mother could never tolerate. There was a reconciliation, which thankfully resulted in the birth of my brother, but in 1930, a new infidelity perpetrated by my father’s relentless drinking habits ended the couple’s precarious equilibrium. That second separation was responsible for our arrival at the Blue House on Londres Street of Coyoacán, today the Frida Kahlo Museum. For my mother, moving there meant coming back home, since that is where she spent most of her childhood and youth.

As far back as I can remember, my mother never complained of the unfortunate facts of her separation. She always held closely the secret of the suffering that living with my father meant for her. She was a kind and understanding person, always well disposed to express good things about those who surrounded her.

Albeit at the time I was only two years old, the divorce was a great psychological impact on me. As I already mentioned, it was from the one-year reconciliation between my parents that my only brother was born. Antonio Pinedo Kahlo was later to become a noted photographer just like my grandfather Guillermo Kahlo. (This book features a photograph that Toño took of our Aunt Frida.)

For obvious reasons, I do not have a clear idea of where I lived with my family prior to being four years old. I do remember, however, that after I turned five, we were already living in the back of the Blue House, “the big house,” as we used to call it.

The Mexico that I lived in was not like modern Mexico. The little streets of Coyoacán were far from the ample asphalt avenues that we have nowadays. During the rainy season, when the ground became muddy and the holes in the pavement became deadly traps, my brother and I would go to elementary school riding a donkey, which we found most amusing. We spent our first years in a public school that still exists in the corner of Centenario Street, exactly where the Coyoacán Square begins—the “Protasio Tagle.” Whenever I pass nearby, I see myself as a child always defending my brother, who was then a little plump and a frequent target of the jokes and even the violence of the neighborhood’s children. Even worse, they would accuse him of arrogance for being Diego de Rivera’s nephew. That is why I learned how to get into street fights with boys, some of whom, I must say, were as much as two years younger than me. I am amused by the fact that the muscles of my right arm are more developed than those of my left arm, and my right hand knuckles still bear the scars of such fights.

But I did not learn how to fight on my own. No, I certainly had very good schooling from the men who worked as bodyguards for Leon Trotsky. In January 1937 Trotsky came as a refugee to the home of my uncle and aunt. The bodyguards warned me that I had to be prepared to respond to aggression, and they trained me.

In fact, I must admit that I never was a peaceful girl. I had to go through several schools because of my bad behavior; specifically, I could not tolerate any bad comment about Diego, Frida, or my country. Whoever the aggressor was, whatever the age or sex, in an instant I would entangle myself in a fistfight with anyone. That is why I went through the Maddox Academy first, then the Madrid College, and finally the Helen Institute. Someone once asked me if my mom was not capable of disciplining me and somehow controlling my combative personality. Well, the answer is yes, she could have had she wanted to do so, but the fact is, in a home governed by those two gigantic captains, Diego and Frida, nobody would have paid attention to a little sailor shouting “land!” When we came to the Blue House, my brother and I were both still very young, and my uncle and aunt really went out of their way to take care of us. One of our first needs was to defend ourselves from the attacks of our schoolmates.

One day things got so out of control that my uncle had to go to school to avoid my expulsion. A foreign girl asked me how was it possible for the “fucking” Mexicans to eat their nauseating traditional food. I asked her if she could come with me to the bathroom for an answer. Once we were there, I started insulting her mother, and I had her take a plunge in the toilet. She was about to drown when a teacher heard our shouting and managed to stop me. She took me to the principal’s office growling with rage, and he decided to expel me for aggressive and violent behavior. I don’t know how my uncle came to know about it, but as I was on my way out of the school (then the Madrid College), he stormed in and transformed into a real madman. The whole thing was tremendously impressive, because Diego was an enormous man, and as if this was not enough, he always carried a gun under his belt. To the teachers and staff members who came to welcome him, he shouted, “Bunch of whimps!” He then asked the principal what had happened, and as the man explained the events, he exploded, “You go ahead and expel my niece and see what I will do to you!” The principal quickly changed his mind, “No, Mr. Rivera, please accept our apologies… I did not know that this girl was your…” But without letting him finish, my uncle retorted, “I want to know the name of the little brat that dared to insult our country. You already had me come here. Now I want to take Isolda with me and…” The principal, extremely nervous, added, “No, no, you do not have to take anybody with you; please give me just a minute. I will immediately call one of our teachers and…” That is how the quarrel finally came to an end.

Of course, under the circumstances I had done what I thought to be fair. I acted in accordance with what I had heard in the Blue House, and in a way, that was completely coherent with the kind of values that were instilled in me. My occasional raptures of anger, whenever my country was scorned, were received with understanding by my uncles and especially by my aunt.

It was not infrequent for my brother and I to be playing in the backyard or in our treehouse when the grown-ups would suddenly yell, “Let’s go to the basement quickly, because there are going to be gunshots around here,” or because an attempt to kill someone was feared. I did not fully understand what an “attempt” was. All I knew was that in such instances we had to run as quickly as possible to the basement. I would then look for my brother and disappear with him down the stairs. The basements of the Blue House were always very clean because my aunt Adriana Kahlo Calderón kept them orderly and tidy. All the Kahlo women were remarkably clean, but Adriana went too far with her obsession for spotlessness; she would even mop the flat roofs.

Talking about Trotsky, I remember him as a very beautiful man, a disciplined, unpretentious, and caring human being. He had a way with children. I would shower him with kisses, and he never minded my affection. I was fascinated with his beard. He had piercing blue eyes, eyes that made you feel naked, eyes that would transfix your soul. He loved me very much. I never felt inhibited by him, as I do now when I recall these images in my effort to prevent them from perishing.

I must confess my lack of knowledge to fully understand the exact dimension of this Russian revolutionary, this extraordinary man with whom I had the privilege to live. Not only was he sensitive, but also strikingly handsome. His most notable feature, however, was his intelligence. (I have never tolerated ignorant people, and my appreciation for intelligence is infinite.) He learned his first Spanish words from me. I taught him a little song that went something like this: “I have two little eyes that know how to see, a little nose to breath, a little mouth that knows how to count, and two little hands to applaud.”’