John Kinsella / Russell West-Pavlov

Temporariness

On the Imperatives of Place

Narr Francke Attempto Verlag Tübingen

In time, I started work on an essay with Andree Gerland on Hölderlin’s great ‘Half-life’ poem and close consideration of this manuscript (which Andree gifted me in replica).

I wish to thank Curtin University, where I am Professor of Literature and Environment, for a Curtin Research Fellowship which has supported my participation in the writing of this book, and assisted me financially in the visits to Tübingen which have facilitated the dialogue between myself and Russell West-Pavlov. I also wish to thank the Curtin University School of Media, Creative Arts and Social Inquiry for a financial contribution to the publication. And much thanks to the ‘Literary Cultures of the Global South’ project at Tübingen University for supporting my visits to Tübingen, and all those connected with the project.

Special thanks to Tracy Ryan for her ongoing support, and also to our son Tim.

Some of my pieces have appeared on the blog I share with Tracy Ryan, Mutually Said: Poets Vegan Anarchist Pacifist and Feminist. And acknowledgement to the following occasions where sections of this book were given as papers: Australian Academy of the Humanities’ 48th Annual Symposium, Humanitarianism and Human Rights, the Perth Literary Youth Festival: Eco-Futures, and Sydney Ideas (at the University of Sydney). Also acknowledgement for first publication of some of my pieces to the journals: Angelaki, Cordite, Poetry Wales, Vallum Magazine and Rabbit. And special thanks to Andrée Gerland for the event we did together in Tübingen: Hälfte des Lebens at the Hölderlin-Gesellschaft in 2017.

And many thanks to Alexandra Leonzini for her copy-edit (not easy working with such a conversational and free-ranging text!), and also Sara Azarmi for replacing my lower-cases with capitals in the ‘Monologues’ for the book-version of the manuscript.

Permission to reproduce images of her artwork was given by Filomena Coppola; many thanks! Thanks to University of Queensland Press and The Estate of Michael Dransfield for permission to use an excerpt from ‘Geography’. Premission to use an excerpt from Kim Scott’s ‘Kaya’ was kindly granted by Fremantle Press. Picador Australia gave permission to reproduce my poems ‛Wagenburg’ and ‛Tübingen Peace Oak’. “Of Being Numerous” by George Oppen, from New Collected Poems, copyright ©1968 by George Oppen. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishung Corp.

Oh, and apologies to those who don’t subscribe to an ‘open’ conversational and divergent style: the rhizomes, roots, and trails through the textual scrub are an essential part of what this book is trying to be, and a result of what it is trying to resist. It is, to my mind, a living and activist text, and a text of dialogue, conversation and interaction—all conducted with due respect, I hope.

I would like to thank Anya Heise-von der Lippe, Sara Azarmi, Alexandra Leonzini and Matthias Schmerold for assistance with the textual technology.

Thanks also to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) which funded, within the framework of the Thematic Network Project ‘Literary Cultures of the Global South’, several of John’s stays in Tübingen, thereby making the dialogue possible in its earliest stages, as well as assisting in the costs of the publication.

A word of thanks is due also to Stephen Muecke, whose fictocritical writing has been a source of inspiration and a model since the day, shortly before my leaving the country behind, I discovered Reading the Country in the National Gallery of Victoria—and for friendship and advice dating from Stephen’s incumbency of the Hirschfeld-Mack Chair in Berlin in 2008-9. In a not dissimilar manner, the ‘episodic’ writing of my friend and colleague David Medalie has informed the structure of this book. Again, I’d like to acknowledge my debt of formal inspiration to his writing. Thanks are also due to Michael Titlestad for giving permission to reproduce extracts of an article on Medalie's work that originally appeared in English Studies in Africa 58:1 (June 2015). Permission to quote Michael Hamburger's translation of Hölderlin's “Patmos” (from Poems and Fragments, 2004) was kindly given by Carcanet Press. Angus and Robertson gave permission to quote from A. D. Hope’s poem ‛Australia’. Curtis Brown gave permission to quote from W.H. Auden’s poem ‛In memory of W. B. Yeats’.

Thanks to Joshua, Iva and Niklas for getting on their bikes and helping with the concretions at the Neckarinsel, the Brechtbau and the Burgholz.

And of course, thanks to Tatjana for lovingly sharing—indeed making possible—talks, walks, thoughts, and many other shared experienced that were, from the outset, ‘about time’.

Both of us would like to thank Philip Mead for his steadfast friendship and mentorship over the years, and, in a sense, for getting the ball rolling. This dialogue, and this book, would never have happened without him. Thanks to Alexandra Leonzini, Joseph Steinberg and Anya Heise-von der Lippe for their assistance with the production of the text.

We would like to thank the anonymous external reader for valuable feedback.

And we would both like to thank Andrée Gerland for his friendship and humour, and for his sense of what poetry and the Global South are all about.

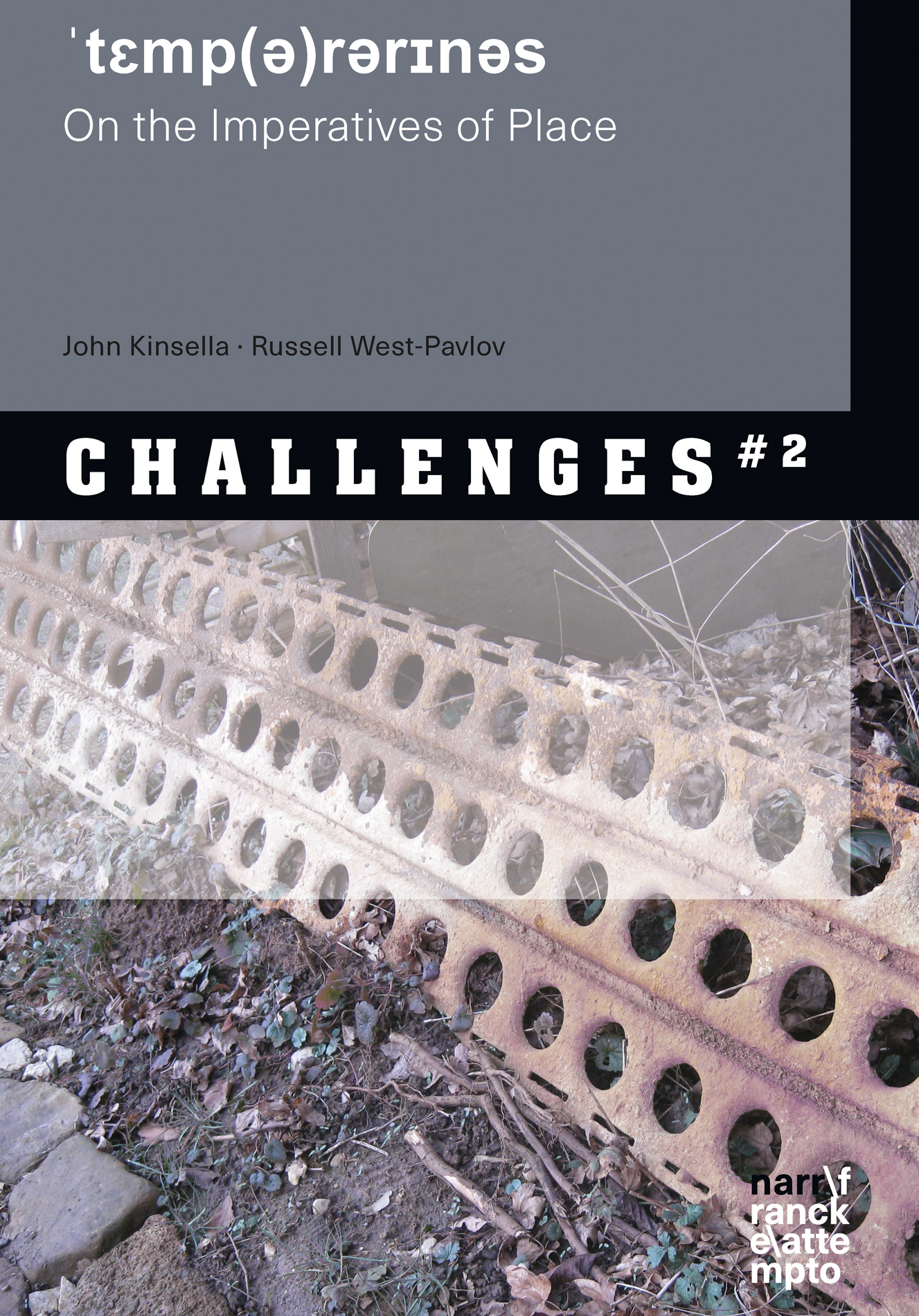

Page 12: Steel Matting, Wankheimer Täle © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 22: Cartridge, Wankheimer Täle © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 30: Ant Concretion © John Kinsella

Page 36: Ant Concretion © John Kinsella

Page 40: Dozer Concretion © John Kinsella

Page 50: Erdrutsch Sign, Schönbuch near Bebenhausen © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 68: Herbst Concretion with Ripples, Neckar opposite Hölderlinturm, Tübingen, Text © John Kinsella, Image © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 74: Ant Concretion © John Kinsella

Page 76: Proximity poem © John Kinsella

Page 86: Diagram © John Kinsella

Page 94: Blaulach Ice, Tübingen © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 106: Ruin, Wankheimer Täle © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 114: Window and Shadow, Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 166: Botanical Gardens © Filomena Coppola

Page 170: Pebble © Filomena Coppola

Page 178: Unexploded munitions sign, Wankheimer Täle © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 184: Military Training Area sign, Wankheimer Täle © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 186: Mirage F1, University of Pretoria © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 200: Eucalyptus, Mirranatwa, Victoria Valley, Grampians/Gariwerd © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 202: Omiš and Cetina River © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 208: Zlatna vrata, Split © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 210: Zlatna vrata, Split © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 214: Split main station © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 218: Brechtbau Concretion, Text © John Kinsella, Image © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 222: Terraces above Kaštel Gomilica © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 224: Track above Kaštel Gomilica © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 260: Mushroom rock © John Kinsella

Page 300: Track near Landkutschers Kap © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 304: Wagenburg, Französisches Viertel, Tübingen © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 308: Hochsitz, Landkutschers Kap © John Kinsella

Page 310: Anomalous Concretion, Text © John Kinsella, Image © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 312: Hochsitz, Bläsiberg, Image © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 316: Track near Burgholz © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 318: Sun Orchid Concretion © John Kinsella

Page 322: Mungart Concretion © John Kinsella

Page 336: Classical column, Natursteinpark, Wankheimer Täle © Russell West-Pavlov

Page 342: Mungart Concretion © John Kinsella

It glints dully on the side of a branch of cobbled pathway that passes through a gap in a straggly hedge. It is a strip of metal sheeting—laterally ribbed, punched with an even array of holes, a long piece of mattly rusted steel not quite flush with the ground so that a sort of malaise emanates from its patently temporary presence. It’s a metre-long length of so-called Marston Matting, or Perforated Steel Planking (PSP), which has migrated down the hill from the erstwhile French military training areas around the Wankheimer Täler, to the residual hippy trailer park that we call the Wagenburg—a now more-or-less permanent settlement of construction-workers’ caravans converted into a sort of a commune-cum-trailer park. This sheet of Marston Matting is probably of American origin. The stuff was first manufactured during the Second World War for use in the Pacific campaign and the invasion of continental Europe. The prefabricated matting was intended to provide an easily assembled road or runway surface to stabilize muddy or marshy ground. The individual elements were perforated to reduce weight, given lateral corrugations to stiffen them, and were equipped with a hook-and-slot system on opposite edges to allow each sheet to be connected to its neighbours. The modular units were designed to provide an artificial ground more permanent that the shifting soil they covered. But by the same token, they could be transported easily, laid quickly, and if necessary, ripped up equally rapidly to be rebuilt elsewhere.

Typically, the steel matting has always been geographically mobile, also being used in Germany, for instance, to strengthen the runways at Tempelhof and Tegel airports during the Berlin airlift. This is perhaps the ‘origin’, if one can use this term at all for such ephemeral building material, for the matting that I am photographing here. Marston matting has been frequently reused for more peaceful purposes than originally intended: as fencing material, as door strengthener, or in one of my favourite examples, as wine rack (you can slot a lot of bottle necks into a slab of Marston!). Symptomatically, when I went back to the Wagenburg to take more photos of this material, I discovered that it was no longer where I had last seen it. It had migrated onwards on its trajectory of serial temporarinesses.

The steel matting was produced with a high manganese content, so that it was resistant to corrosion, as the reasonably good state of the sheeting I found showed. This means that, paradoxically enough for a building material designed for the construction of temporary runways and road surfaces and frequently transported to new sites and re-used for diverse projects, it is itself endowed with a considerable degree of permanency. A recent clean-up of the now decommissioned military zone (one of a series that has progressively removed old munitions and military junk from up on the hills) dredged up quantities of this steel matting in pretty good nick. It is entirely plausible that the sheet that I photographed has an eighty-year history of repeated usage in various theatres of war or mock-war, from the Second World War through the Cold War, into the post-Cold-War era—a concatenation of epochs that has seen so many low- and high-tech conflicts around the globe. The steel matting, in its very material existence, or perhaps more appropriately, existences, is an embodiment of the dialectics of temporariness and permanence that is a core preoccupation of this book.

This relic of numerous wars, non-wars or proxy-wars, lying about in a hippy commune on the edge of a South German university town, fascinates me. It seems emblematic of the relationship to place that John Kinsella and I explore in these pages. The sheet of matting lies on the ground, propped lightly against the base of a tree trunk, half in contact with the earth, half floating in the air around it—displaying its readiness to go elsewhere at the drop of a hat. The matting is a prosthetic analogy for the ground, porous like the soil and its latticework of crystalline particles, constructed of minerals drawn from the earth, of it but not of it. It is a modern technological hybrid, derived from but somehow alien from the ground. It is both related to the soil, yet oddly remote from that with which it so intimately snuggles.

The matting creates around itself a palimpsestic, laminated configuration of elements—earth and air, perhaps also water and fire—which might be construed as a concrete metaphor for the very nature of the temporality of the earth and our modern relationship with it. Indeed, the iconic similarity between our title, tɛmp(ə)rərɪnəs (‘Temporariness’)—transcribed into International Phonetic Alphabet in a gesture towards the contingent singularity of the verbal speech act itself—and the perforated steel matting is not coincidental. If language, for Heidegger (1949: 24), was the house of being, we implicitly suggest in this way, that temporariness, in its material and linguistic forms, is the latticework of becoming.

Coeval with the ground, the steel matting both connects and separates the earth and those who stand upon it. The matting migrates, like those who walk or work upon it. The metal sheeting exists in an uneasy semiotic relationship with its environment. Is both an icon of the surface of the ground and a metonymy of it, and in my recycling of it here, a metaphor for the complex relationship between temporariness and permanency that John and I explore in this book. It is also an artefact of war, which destroys many of the relationships that language depends upon and that it seeks to illuminate. So close to nature in its intended capacity of lying layered upon the earth, but so immensely indicative of what Sebald (2004) has called ‘a natural history of destruction’, this sheet of matting is an index of the annihilation of the earth of which John and I are constantly reminded—not unlike Sebald himself, who discovers on his walk through Norfolk and Suffolk ‘traces of destruction, reaching far back into the past, that were evident even in that remote place’ (2002: 3).

I am fascinated by this material—I say it again. It exerts a powerful attractive force upon me. Inert, passive, but at the same time absolutely interactive (any one sheet of Marston matting is designed to slot into others), it also interacts with me. Like a dumb interlocutor, its perforations so many mute interrogations, it coaxes me into speech when I encounter it. An unnatural prosthesis of nature, it behaves, indeed, like any other inhabitant of the natural environment, giving me, quite literally, ground to stand upon in my own capacity as a walker and wordsmith. To the extent that it is there and calls to me, speaks with me, it gives birth to me in this particular instant and instance of my own series of temporary moments of existence.

The matting is a living entity—yes, living: it moves, it acts, it interacts, it signifies, indeed, it is also a site of feeling. It is an emblem of affect—that powerful attractive force that operates at the somatic, visceral level and connects entities, alive or half alive, human or nonhuman, to each other, in ways that cause them to change in the course of the encounter—if only then to disengage, transformed, ready to enter into a new transformative dialogue with a new interlocutor, and on and on, in an endless creative process of connections, deconnections, reconnections. The matting I have photographed is both a visual metaphor of the affect-ridden, affect-driven world we live in and an indexical manifestation of its ‘relational pull’ (Eckstein 2017) because I have been drawn to photograph it.

Yet at the same time, it is also an index of the no-less powerful forces in our world that seek to exploit, divert, pervert and destroy the immense fabric of creative relationships that make up the cosmos: war, environmental destruction, the necropolitical annihilation of humans, animals, the forests and the earth itself. These forces also exert a powerful, sinister and unsettling fascination, meaning, if nothing else, that we can never claim we are not complicit in these ubiquitous processes of destruction (Sanders 2001)—even if that uneasy knowledge founds and fuels our dogged resistance to such forces. This play of positive and negative affects means that even our moral stances, our political engagements, are not permanent places to stand, but temporary site of resistance that in this ongoing war of manoeuver must constantly be reassessed and renewed. No theory, no manifesto, no work of art, is permanent or eternally sufficient. Each of them serves a purpose for a period of time and then, as circumstances change, must be replaced by another one that is more appropriate.

That is why, in writing this book, John and I have implemented the genre of the collage of micro-essays. The book is made up of units that, not unlike the steel matting, can be combined and recombined at will with other units. We have chosen a particular sequence, but of course you can take the fabric of matting apart and put it back together in another sequence or collage as you wish. Indeed, in the process of writing, we have constantly tried out new permutations and combinations of the units making up this book, slotting them together in ever new configurations.

Similarly to the sheets of steel matting, each of the textual units is porous. The perforations reduce the weight of the steel matting. Likewise, the essay has a certain lightness that eschews monumental and the exhaustive modes of academic writing—attributes highly valued in the Germanic academic system in which I work, where the essay, according to Adorno (1991: 3-4), is a subaltern and subversive genre. This lightness arises from the fact that the essay seeks to maintain an open structure that communicates with its environment. Iconoclastically, the essay refuses the customary distance between scholarly observer and the object of commentary. It thus threatens, however discretely, a tradition of ‘science’ (‘Wissenschaft’) that legitimizes its gravitas on the basis of objectivity, that is, non-involvement with its objects of study. It’s a good century since quantum theory recognized that no scientific experiment can take place without the necessary precondition of the ‘entanglement’ of, respectively, observer, scientific instrument and the natural phenomena under investigation (Barad 2007). Yet the essay still creates a stir by virtue of its mixing of the distanced mode of academic commentary and the participatory mode of creative connection—by virtue of its contamination of academia with art.

In its very generic features, the essay is a hybrid genre, thereby advertising, performatively, the nature of its task. Adorno (1991: 14-15) identifies the essay as a genre that is inherently inimical to Descartes’ dictates about the functioning of analytical reasoning at the dawn of the modern—and beyond, right up to the present day. Analysis, for Descartes, divides the problem into a number of atomized elements that can then be addressed one by one. The principle of divide and rule in the world of polemical thought. Or the principle of the anatomy lesson, that violently takes the body apart in order to understand its workings. The essay, itself at first glance a fragment rather than a whole, does none of this, says Adorno. It addresses an issue in its entirety, in its complexity, without seeking to dissect it and thereby reduce its living, organic complexity. By the same token, it renounces any form of totality or exhaustiveness, contenting itself with the contingent, the provisional, the temporary—in other words, the only sort of encounter that can be had with a dynamic, actantial Other.

In this book, our essays, themselves dynamic entities, enter into a dialogue with one another. Within that conversation, the essays, apparently stable in their black and white adhesion on the page, are in fact transformed by the manifold and shifting connections that the intelligent and alert reader, if she listens carefully to their subterranean or submarine murmur, will hear them making among themselves. Indeed, although we have orchestrated these pieces in a certain configuration, John and I have constantly been surprised by what the micro-essays get up to among themselves when our backs are turned. Accordingly, we have been reminded, time and again, of Thoreau’s (1908: 8) words: ‘We are made to exaggerate the importance of the work we do; and yet how much is not done by us!’ We are aware that our own configuring work leaves ample space for the essays to work their own magic and weave their own connections without our help.

But that is not all. The essays seek to engage in turn with their environment, to be open to the world. One might imagine the steel latticework as a material icon or a very objective correlative of the written text—its lateral corrugations mimicking the lines on the page and the perforations the chain-like sequences of the words themselves. Conceived of thus, it is striking that in this visual simile both lines and words are staged as absences: the lines are long open grooves and the words have literally been punched out on the production line. Both are open to the air. The steel matting provides a literal visual metaphor of what Eco (1989) called ‘the open work’. Literary poesis, and by extension, intellectual creation, does not result in an autotelic, autonomous work of art or a hermetically sealed work of scholarship. Rather, from the outset it is engaged in a constant dialogue, from the smallest unit of the letter or the phoneme, with its neighbours. The visual metaphor of the steel latticework, even though it portrays an artefact that is independent and may travel, suggests a notion of creation that eschews the paradigm of Saussurean difference. Rather, it imposes a notion of interrelationship as the driving force and the underlying precondition of artistic creation and inquiring thought. Each of these essays seeks to communicate with its neighbours and could not exist alone. Each one entertains a myriad of vital connections to the earth, to the forest, to animals, to other walkers, to the wind and the clouds.

To that extent, this collage of essays stands, in the manner of a complex synecdoche, for a worldliness that we believe is the only viable mode of being for the humanities if they are to survive as part of the educational institutions of the future. This book is a plank—modular, open-ended, dialogical, contingent—in a programme for a temporal (as opposed to spiritual) humanities that has yet to be invented, but we believe to be our only chance for saying something of relevance in the era of multiple global crises that forms our dangerous Now.

RWP

River rising out of Black Forest is the river

you walked past and will walk past again, again,

Neckar rising and falling all the way to the Rhine

at industrial Mannheim, flowing with swan

families keeping zones, maintaining half lives

in the dip of seasonal sheddings and re-applications,

wingspread to hold warmth, to harbour

the cores of their legacies, codes we stumble

around, taking photos. And then, downriver

from Tübingen, on a train to Stuttgart,

later approaching Kirchheim, across

the waters, hook of the river, swans familiar

but different, chain of being, or reaction

against corruption of fundamentals.

Across there, summer family, Schwäne,

Gemeinschaftskernkraftwerk, GK N2

with its hybrid cooling tower suppressed

volcano eruptive as the Börse Frankfurt

doesn’t want to be, steady steady

goes the hebephrenic—broody reactor

in its oven nest reminds you of Frost’s

‘American’ ovenbird, but this can’t be enclosed

in a sonnet reactor vessel, can’t be shielded

against its wild prosody when life goes on

and on all around, cheap land for wealthier than-

usual families who don’t maintain

anxious states, who let the becquerels

wash over them in health denial.

The big flood of extra warm water

in 2004, the heating river with happy

expanding fish, the Simpsons laugh-off

at mutating presence, those drones

out of Stuttgart, the ongoing states

of warfare. Wonder if the mines in Western

Australia on stolen land stealing spirits

and unbalancing will feed its last years,

the swans’ white labours in the wastes,

the ‘historic hiking path’, the respect

a Mayor has for tradition and rites

of way, trek on to Heidelberg escorted

through the plant by ‘guard and German

shepherd’. Matrix of traversal. Swan spectres.

Wondering how people could live within

a few hundred metres of the plant, of Unit 2

itself, how? Benign as ‘Wouldn’t know anyway’,

and ‘Better dying first than lingering longer

being further away’. Quid pro quo choice

exchange not likely to rouse as much interest

as Boris Becker’s financial solvency or Bernard

Tomic’s ‘un-Australian’ statement of fact: ‘little bit bored’,

shattering a sponsor’s illusions of a too busy to

notice enculturation. Radiation gets places,

works its way in, speaks its mind. And white swans

mute and full of voice, the songs of culture pledge

benefits of plant, and company’s people-skills,

localising instillation. Benefits. Privileges.

Of ‘German Engineering’. Safe as houses.

But what do flight and song and Hölderlin

have to do with violence of matter, of a split

in the forest’s fabric, the potatoes bulging

in the fields right up to the ramparts,

tours through a ‘sterile’ environment:

clean is unseen. So who’s to watch CNN

on atomic television, or atomic rail past steam

rising or the quiet hum of plant transpiration?

These networks of empowerment, these liberations

of carbon futures, carbon credit slaughterhouse?

Incongruous change of tone, shiftback phonemes,

almost passive observation recollection

data collation—stay safe within the poem.

All these voices that make schematics, make

policy for energy to cloak the wor(l)d, to screensave

and dilate our spectres. Late day travelling

past, even in summer light with the risk

of a shower, your swans show the way,

cygnets trailing, blazing a generational

pathway; for no Reactor Birds are alone

for long, and even diminishing, register

strong—what does it mean outside

the ancient sources, the languages

that have gone into making up the grid?

And to cap it off, waste from elsewhere

arrived on a barge, a ghost-train passes

on the other side, on the far bank, shielding you?

Or—later, later—on the intercity express from Mannheim

to Frankfurt, the ball in play, everything in motion,

the Rhine enabling Biblis plant, the Rhine in role

of co-dependent, the Rhine regurgitating loops leaks

breaks quad cooling tower symmetry to placate

Unit A and Unit B pressurised water reactors,

gloriously twinned with Balakovo’s pride,

ovens warming to swan silhouettes, a Lotte

Reiniger manic design Ordnung, the Neckar

warm water merged with the Rhine warm water

fed as wedding party bliss! O, but stymied with decommission,

that slow trek towards non-existence as if it never was,

wish-fulfilment a trace in cabbage fields. But good ol’ GKN2

back up the tributary will stay hot under its collar!

True, true... Neckarwestheim is not on the railway

but from across the river you join its pseudo

symbiosis with plant, with the history

of atomic birds: Höckerschwan, Graureiher,

Bussard, Kohlmeise, Gartenbaumläufer,

and with lists keening through glass

you absorb becquerels to add to your stockpile,

weaponised psyche to expand human

consciousness, ingenuity of refusal and acceptance

gathering as the train slows at Kirchheim,

Neckar still rising out of the Black Forest far back,

as you always travel facing forward if given a choice.

These zero-sum gains in which spectral swans

are winners averting glances, GPS propositions.

JK

The residues of the military trying to keep a firm footing on ground they’ve disturbed, disrupted, brutalised, are a reminder and an affirmation of their failure to hold what they’ve appropriated, no matter how ‘resilient’ their technology. The ‘essential’ nature of manganese for not only anti-rust qualities, but also its qualities of shock reduction on steel, made it a deeply desired commodity in World War II, and the desire lines lead to the ‘neutrality’ of Sweden (Swedish ships carried and protected German ore shipments during the war) and, say, the Artillery Mountains in Arizona. Manganese mines, like all mines, are places of great natural and cultural disturbance. The exploitation—new waves of colonisation—of African ‘resources’, including manganese, developed multifold during World War II. All intermediaries between the earth and our feet, between the earth and objects of human design—the ‘conductive superhighways’ of the false anthropology—create a buffer that can only be permeable. A common sight in rural areas around the world is the degraded macadam that has been defeated by ‘weeds’ and tree saplings, breaking through, remaking habitat. The reclamation of steel matting of many wars and false wars, a reclaiming into the domestic porousness of forest not as monopolised capitalist-military resource, but as a place of nature in which humans are also nature, is a pragmatic dissolution of the vicariousness of conflict and violence, of the sundering of earth to conductivity. All wars are won or lost depending on lines of supply and communication. The matting allows vehicles to move where they couldn’t move of their own volition, or where they would be impaired in the usual movement. Tracked vehicles incorporate their own ‘matting’, of course, but even these sometimes require the extra ‘footing’ matting provides. And now the matting that fitted together so readily and efficiently is moving as if compelled by itself, and not by the military. A life, maybe, outside conflict—an absorbing of the less destructible into the forest, into the dwelling of ‘hippies’, into the liminal spaces of the forest-edge dwellers. In the personal essay we are often ‘reminded of’ and draw analogies because we wish to frame the run of words and yet make it porous enough for ‘us’ to dip out and re-enter at will. This matting is necessary for the act of reading to ‘walk’ over the textual roadway laid down to enable the journey we think we require when beginning a text and imagining its possible ends. And in this spirit, yet another ploy, I am reminded of living in ‘the shack’ in the cow paddocks on the edge of the creek deep in the southwest of Australia, a few kms outside Bridgetown, with marri forest edging nearby, and a giant colonial walnut in the vicinity of the shack. And mud. In winter, it rains heavily and gets muddy. And in the same way turbulence is on the increase due to climate change, and aviation thinkers are trying to out-think the conundrum of flying through what is increasingly difficult to fly through, their machines contributing strongly to the cause of the effect, so too the erratic weather patterns over the southwest produce erratic dries and wets, and the earth underfoot behaves in unpredictable ways. But when I/we lived there, it was muddy in ‘winter’ and we laid hessian sacks on the ground outside the front porch (an unlockable ‘front door’, and no back door at all), to relieve the abjection and to make passage to the vegetable garden more practical, and to the toilet which consisted of a steel drum of high manganese content with a wooden seat above it so you’d hover over a pit of excrement, to be covered in lime after heavy usage. The sacks had been used for ASW wheat, which wasn’t grown in any quantity around there, but was grown to the northwest of the district in vast amounts over vast areas—areas I was more familiar with. The sacks had been acquired elsewhere and brought in, though we had no car and only walked places or hitchhiked. I cannot recall how we got the sacks there, so the designed usage was consigned to the temporary, and a pragmatic reinvention of use put into action. But more planned than one might think. I’d seen the sacks used for this up around farms throughout my childhood. The sacks were a little resistant to mud, but not particularly—the fibre grew sodden. Eventually the mud soaked through, to join deposits from our feet, to fuse. Walking the forest around the Wankheimer Täle with Russell, I was fascinated by the residues of an old stone road he showed me. We took many photos of the stones, our own feet, the dry mud around them. I didn’t find it abject, but my feet were well shod. The stones were fixed, and had likely been so for hundreds of years, but they were intrusions likely of the place into the place, a looping intervention but also continuity. Walking, we might wonder a-priori and know they must appear where the track becomes difficult, where it descends from field to forest. These objects with human defintion calling up experience. A complex array of presence and habitat. A challenge to the temporary, in the way all ‘time’ is inevitable and terminal and will demand its end (and, for that matter, all time is present in the moment, the singularity—ends and beginnings are relative terms). But this is really a rhetorical ploy, because in the spatial maze there are only dead ends (which become a propaganda of ‘beginnings’), and not a ‘solution’ encompasses reaching an emanating, enlightening ‘centre’ (which merely tells you that you have been on a journey). And the journey is as continuous as time which is contained within the singularity of the moment—a drawn point containing many if not all points. Thus our compulsion to make narratives of journeys, of a walk from a to b. It is a story of all time and no time, of a very specific (if meandering) route, and all space (the infinite numbers of points between points).The matting is a paradox. The matting will always move, and, indeed, it was designed to do just that. But it also moves against its design purpose, and in doing so mocks the violence and industry that prompted its creation. Conservative ‘red pill/blue pill’ Matrix binaries are served by the matting—we can seek knowledge and its consequences, or remain blissfully ignorant. But bliss and knowledge are so intimately connected that the binary is rendered absurd before it is made. The matting is not a binary, or even part of a binary, but a recognition that even the most violent human constructs are subject to the ‘inevitable temporality’ of ‘nature’, that the materials of its making are the material it is deployed to control. An absurdity. A theatre of self-loathing. The discursive essay has to break down into ramblings and let the mud through while retaining its trajectory, its ability to move through and over rough terrain, contrive its narratives of self-preservation. Or as the rhetorical ‘or does it?’ transports us rhizomically and atmospherically over the same land without damage. Termites scaffold their food externally and internally—and they feed the earth as they eat a tree’s deadwood. The tunnels in a termite mound, the tunnels of digested material through the dead centre of the log, are the matting created and possessed without war being enacted. The termites’ is an essay as form without violence.

JK

Where is here, where is there? Where is home, where is away? John has just written a poem about signing the petition against the accident-ridden French nuclear power plant at Fessenheim—just across the border, on the other side of the Rhine, only 100 km from here. Where is here, where is there, when the reactor flushes its contaminated cooling water back into the Rhine and its tributary the Neckar, and the winds can carry any particles that the plant may emit across the black forest to our adopted Swabian home further east? So much anxiety about belonging, about refugees, about keeping foreigners out—the basis of the shocking right-wing surge in the 2016 state elections—and so little anxiety about a more potent ‘foreign’ threat, one that comes from over the French border. It’s that threat that ought to be causing us a deeper anxiety. Although even that ‘foreign threat’ is no less dangerous, so Tracy tells me, than the domestic radioactive leaks from our ‘own’ Neckarwestheim and Neckarsulm plants further up our own oh-so-idyllic Neckar.

While we are on the subject of belonging and ‘here’: Neckarwestheim is twenty kilometres up the Neckar from Marbach-am-Neckar, where the German National Literary Archives are housed. The great treasures of German literature—manuscripts, letters, rare first editions, all the textual paraphernalia accrued since the elevation of Luther and Goethe and Schiller to icons of national tradition—are irrigated by the radioactive waste that threatens to put an end to all traditions, not merely those textual ones that are enshrined upon the Schillerhöhe looking over a bend in the Romantic Neckar. Fluid half-life against the river-like flow of a literary legacy (albeit one tarnished by the book-burnings), that I could experience live, tangibly, when I visited with Amadou from Dakar, to investigate Sebald’s scribblings from the Fens.

It’s time to recalibrate our notions of where we belong: perhaps, as Vivieros de Castro (2014) would have it, our home is a shared human continuum of humans and nonhumans, all experiencing themselves as intending persons, and thus as sites of intention and ethical action, but seeing various natural worlds around themselves. We and jaguars all have a taste for beer, but what we take for beer (IPA, Hefeweizen, or blood) is a matter of species-specific taste, a question of what is prey for each predator. Today, that common ‘humanity’ of human persons and non-human persons is underscored all the more so by a grotesque inversion. If we are predators one and all, beer-drinkers alike (in best German tradition), we are all, none the less, also ‘prey’: we are prey to that predator technology unleashed upon the world by human persons unaware of their place in a continuum of personhood and determined to dehumanize their own putatively singular humanity.

Here and there is neither here nor there—what counts, it would seem, is our common personhood across a spectrum of species and across a spectrum of places—whose differences, so important to childish nationalisms, are of no regard whatsoever to the monster radioactive ‘person’ preying upon us all.

RWP

In all we do, whoever we are, wherever we consider ourselves as coming from, we should be aware of the impact we have as individuals, and collectively, on the natural environment. We should be critiquing our very presence. That is not to say that we shouldn’t ‘be’, not at all, but that we should be aware of being—its contingent privileges, and costs. And every word we use in discussing our presence should be scrutinised.

For example, the word ‘cost’ itself. What does it mean in this context? Are we reducing habitation and ecology to a system of profit and loss, of wealth accumulation? Obviously not, but we don’t have to be poets to know that words carry weight beyond our intentions. Yet as poets, we can always neologise—where a word is lacking, create one!

For me, when I talk of environment, I am usually talking of what most would call ‘the natural environment’. This might suggest an environment untrammelled by humans, or it might also mean an environment in which humans co-exist with other life-forms in a more ‘harmonious’ way. The problems of ‘harmonious’ aside—for ‘harmonious’ will only, in the end, ever refer to the human condition, not the non-human—I will say that I mean ‘natural’ and ‘human-made’, forms of environment, in the same way that ‘landscape’ is actually about human impact on the natural environment.

We also need to consider the ‘human-made’—the ‘built environment’—in all discussions of environment and ecology, because ecology is necessarily anthropomorphic, and should be critiqued and understood as such. From the garden through to the house, the village through to the city, from the park through to the forest, environmental language is built out of comparatives, slippages, gains and losses. Environment is also about immediacy, about the conditions under which the human—and, for me, as vegan and (an?) animal rights activist, the animal—subject is present. It’s a complex notion for what is often the simplest descriptive reference to nature and place.

So, as I will be talking about ‘environment’ and activism—which is an infinitely complex variable in itself—I do so with the understanding that its many meanings can easily shift in and out of focus as I move through this text, this speech. And given that we are dealing with ‘eco’ and ‘future’ in this festival, this discussion, we are confronted by a question of ecological environment specifically, and what is likely to remain the same (little) or change (a lot) as we go forward through the years.

We all know ‘oikos’ is house—in fact, a whole discourse has developed around that transition from the ancient Greek into the ecology of modernity. I’ve always found the word in its biological usage, the relationship of the organic to the inorganic physical world, a colonialist appropriation. The state of ‘our house’ or ‘the house’, depending on the grammatical article you select, is both an objective and subjective condition. We wish to keep our house well, we wish to keep the house well; we wish to wreck our house, we wish to wreck the house. There are choices of action and choices of possession in this. And dispossession.

Surely we need to ask whose house it actually is, and whether or not it has been ‘stolen’. Further, as we feed on technology, we should ask whose house is being robbed to give us our consumer comforts. Because you can be sure human houses are being robbed, as well as animal and plant houses. Consumerism is theft.

To my mind, many of us in Australia are calling it our house when it’s actually someone else’s house. We are on Aboriginal land. Fact. Now, don’t get me wrong, I believe we can all co-exist, and I am deeply committed to an open-door policy regarding immigration and refugees (in fact, Open Door is the name of the poetry book I am writing at the moment). But in the case of the exploitation of the house for wealth-accumulation, there has to be compensation, or better, the house shouldn’t be wrecked at all. Co-existence is possible and desirable, but it should come under conditions respectful to traditional owners and custodians. And I say this as one who doesn’t believe in ‘property’ or ‘private ownership’.

But what of the environments and their ‘houses’ that can and should exist outside the human? Well, there are many of these, and some actually exist inside the human! They are ecologies of bacteria and viruses that thrive in the human body, their environment, their house. Some of these bacteria we consider ‘good’ and allow