Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 The Edentulous State

Aim

Outcome

What is an “Older Adult”?

Epidemiology

Attitudes to Edentulousness

Anatomical Consequences of Edentulousness

Alternatives to Complete Replacement Dentures: Implant-retained Prostheses

Future Directions

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 2 Changing Times: The Dentate Elderly

Aim

Outcome

Attitudes to Teeth: Influences on Patients

Dentate Older Adults: Are They All the Same?

The dentally-aware, low-maintenance patient

The dentally-aware, high-maintenance patient

The dentally unaware patient

Controlled Transition to the Edentulous State

Conclusions

Chapter 3 Threats to Oral Health in Older Adults

Aim

Outcome

Factors Leading to Increased Tooth Retention by Older Adults

Threats to Oral Health

Tooth retention

Oral Pathology

Oral cancer

Oral cancer: the role of health promotion

Denture-induced Pathology

Candidal infection

Denture granuloma

Timing of denture replacement

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Conclusions

Chapter 4 Ageing and Periodontal Disease

Aims

Outcomes

Introduction

How Big is the Problem?

The Range of Age Changes Seen in the Periodontium

The Gingival Tissues

Epithelium

Connective tissue

Cementum

The Periodontal Ligament

Alveolar Bone

Age-related Changes to Dental Plaque

Immune Response Within the Periodontal Tissues

Healing Capacity of the Periodontium

Influence of Medical Factors

Attachment Loss

The Older Patient’s Attitude to Periodontal Disease and its Management

The Clinical Relevance of Age Changes to the Treatment of Periodontal Disease

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Root Caries: Aetiology, Diagnosis and Management

Aim

Outcome

Terminology

Epidemiology of Root Caries

Aetiology

Host

Microorganisms

Substrate

Time

Risk Factors and Risk Indicators

Diagnosis

Management of Primary Root Caries Lesions

Rationale

Prevention

Oral hygiene

Dietary counselling

Saliva stimulation

Chemomechanical

Fluoride

Chlorhexidine

Caries Debridement and Lesion Recontouring

Carious Dentine to be Removed and the Lesion Restored

Atraumatic restorative treatment

Chemomechanical caries removal

Conventional caries removal: proximal and lingual lesions

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Tooth Wear in Older Adults

Aim

Outcome

Aetiology and Diagnosis

Key Decisions

Management of Tooth Wear

Is there adequate space for restorations?

Fixed restorations

Indications for a removable prosthesis

Planning overlay prostheses

Overlay prostheses: clinical stages

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 7 Endodontics and the Older Adult

Aim

Outcome

Endodontics and the Older Adult

Key Issues

Can the tooth be saved?

Should the tooth be saved?

Can the Tooth be Saved?

Is the tooth restorable?

Can infection be controlled?

Will the patient consent to treatment?

Is the proposed care affordable?

Should the Tooth be Saved?

Medical considerations

Is this a critical tooth?

Endodontic Challenges for the “Old” Tooth

Assessment and diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

PerioEndo Lesions

Primary endodontic lesions

Primary periodontal lesions

Combined lesions

Problems of Access to Infection

Key Changes Which May Compromise Infection Control in the Pulp Space

Increased fibrosis

Diminution of pulp space

Obliteration with irregular calcification

Notes on the Safe Pulp Access in “Old” Teeth

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 8 Functionally Oriented Treatment Planning

Aim

Outcome

Do We Need to Replace all Missing Teeth?

Influences on Tooth Replacement Decisions

The Shortened Dental Arch Concept

Rationale

Indications/contraindications to shortened dental arches

Applications of the SDA Concept

Final Considerations

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 9 Tooth Replacement in Partially Dentate Older Adults

Aim

Outcome

Planning Tooth Replacement

Fixed or Removable Prostheses?

Long spans

Number of tooth spaces (saddle areas)

Soft tissue profile

Status of potential abutment teeth

Patient preference

Fixed Prostheses in Older Adults: Special Considerations

RPDs in Older Adults: Special Considerations

Unbounded (free-end) saddles

Lack of Interocclusal Space

Conformative approach

Reorganisation approach

Methods of Direct Retention

Clasp retained

Precision attachment retained

Maintenance

Reline/rebase

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 10 Overdentures: The Bottom Line for Older Adults?

Aim

Outcome

Rationale for Overdenture Therapy

Benefits of overdentures

Selection of abutment teeth for overdentures

Endodontic considerations

Abutment tooth preparation

Overdenture construction – clinical and laboratory procedures

Immediate overdenture procedure

Complete Replacement Overdentures

Precision attachment mechanisms

Maintenance

Implants versus overdentures

Conclusions

Further Reading

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 7

Prosthodontics – 1

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Allen, P. Finbarr

Teeth for life for older adults. - (The quintessentials of dental practice)

1. Aged - Dental care 2. Prosthodontics

I. Title II. Wilson, Nairn H. F.

618.9′776

ISBN 1850973008

Copyright © 2002 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 1-85097-300-8

With many more people living longer, remaining dentate – albeit, partially dentate – throughout life and having ever-increasing oral-health expectations, the dental care of the mature adult patient is one of the major challenges of present-day general dental practice. Teeth for Life for Older Adults – Volume 7 of the Quintessentials for General Dental Practitioners Series – gets to the heart of this challenge: effective management of the older patient, long-term treatment planning, countering the effects of oral ageing, the maintenance of typically heavily restored and often worn dentitions, and dealing with the many, varied prosthodontic dilemmas the mature adult patient may pose.

A very large and immensely important subject area in contemporary dentistry is succinctly captured in this attractive book. As in all the volumes in the Quintessentials for General Dental Practitioners Series, the easy-to-read text is generously illustrated with high-quality informative images. The care of mature adult patients is often difficult and may be fraught with problems. This book recognises the great diversity of clinical issues that may arise in the provision of this care and provides sound guidance on how best to achieve favourable clinical outcomes in the management of patients in the older age groups. A further hallmark of the books in the Quintessentials for General Dental Practitioners Series is an emphasis on information that may find immediate chair-side application. Teeth for Life for Older Adults is no exception in this regard, as it is packed full of answers to the multitude of questions practitioners ask about the management of mature adult patients. Teeth for Life for Older Adults is a most welcome and important addition to the dental literature.

Nairn Wilson

Editor-in-Chief

As the population ages, dentists will have to provide care for larger numbers of older adults. Improvements in dental health have led to increasing numbers of dentate older adults, but there is a high burden of maintenance associated with ageing dentitions. Older adult patients will present a range of challenges and demands. There will be fewer new edentulous patients, but the threat of total tooth loss will remain a reality for significant numbers of adults for the foreseeable future. Dentists will be expected to provide care for these patients in an era of diminishing resources for healthcare. This text, using currently available clinical and research-based evidence, aims to give the general dental practitioner an insight into the management of older adults. The first chapter gives an overview of the problems experienced by the edentulous patient. The presentation, aetiology and diagnosis of common disease states affecting the dentate older adult are then discussed and management strategies are outlined. The final chapter covers the use of complete overdentures and invites the reader to consider whether this should be the end-point of dental treatment for older adults.

It is hoped that having read this book the reader will be able to:

Understand the consequences of total tooth loss and the desirability of avoiding edentulousness if at all possible.

Recognise that there is an expanding older adult population who are retaining more of their teeth than ever before, and that much of this older population are not willing to accept tooth loss as an inevitable consequence of ageing.

Recognise that there are many threats to the goal of healthy ageing of the oral tissues.

Recognise that health promotion as well as disease prevention is an important aspect of clinical care in this population.

Understand that ill health is not an inevitable part of ageing and that complex treatment is not contraindicated in older adults.

Understand that long-term treatment planning is essential to avoid total tooth loss at an advanced age.

Recognise that, for some older adults, it is acceptable to limit treatment goals to provide a functional rather than a complete dentition.

Recognise the importance of thinking strategically if edentulousness is to be avoided. If roots are to be retained to support an overdenture, this should be the final phase in long term treatment planning.

P Finbarr Allen

I would like to thank the following people for their help in the preparation of this book: Dr Frank Burke, Dr John Whitworth and Mr Mike Milward for contributing chapters; Professor Iain Chapple for his help in the preparation of Chapter 4; Dr Edith Allen for proof reading the entire text; Dr Nick Jepson, Mr David Murray and Mr Francis Nohl for permission to use some of their photographs as illustrations in the text. Finally, I want to acknowledge my former colleagues at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, UK for inspiring my interest in gerodontology.

Population studies indicate that the proportion of dentate older adults is increasing dramatically in industrialised countries. This chapter aims to provide a view of changing patterns of oral health of older adults in industrialised countries.

At the end of this chapter, the practitioner should be aware of the consequences of edentulism and the desirability of avoiding total tooth loss in older adults.

It is often said that age is a state of mind, and to a degree there is no consensus as to what constitutes an “older adult”. Some authors have classed adults over the age of 60 as young elderly (60–75 years old) and older elderly (> 75 years old). In this book, an older adult is arbitrarily over the age of 65 years. It should, however, be remembered that planning to maintain teeth for life in older adults starts much sooner than this. In the past, a large proportion of adults had lost all of their teeth long before this age. Improving adult oral health has led to increasing numbers of adults retaining teeth later in life, but oral disease levels in this age group remain high. Consequently, dentists need to plan early and strategically to face the many challenges posed to maintaining teeth for life in older adults.

The percentage of the population over the age of 65 years is increasing in countries in the industrialised world. This is a reflection of increased life expectancy and the approach of middle age for the “baby boom” generation. In the United Kingdom, for example, the mean age of the population is expected to rise from 38.4 years in 1996 to nearly 42 years by 2021. The number of adults over the age of 65 years is projected to increase by 2.7 million during the same time frame. The proportion of the “elderly” elderly (i.e. aged 85 years and over) in the UK is also expected to rise, from approximately 800,000 in 1991 to 1.5 million in the year 2010.

The dental status of older adults is also changing dramatically. In 1968, 37% of adults (aged 16 years and over) in England and Wales were edentulous. By 1988, this figure for the whole of the UK was 21% and figures from the 1998 UK Adult Dental Health survey show that 13% of the adult population are edentulous. Long-term predictions indicate that the prevalence of edentulousness in the UK will eventually level out at 6% by the year 2028.

The level of edentulousness at the present time is strongly associated with dental problems of the distant past, with those who were rendered edentulous 30 to 40 years ago strongly influencing the edentulous statistic. As the population is generally ageing, and as it takes a long time for age cohorts to pass through the population, it will be some time before edentulousness will be a thing of the past. An examination of the most recent UK Adult Dental Health survey in 1998 shows that one-fifth of the 55–64 age cohort were edentulous, with this fraction rising to three-fifths of the over-75-year-old adults. Even if dental clearances stopped now, which is unlikely, it would take until 2038 before edentulousness was eradicated. While the proportion of the dentate adult UK population has increased, the DMFT index score for cohorts over the age of 45 has not substantially changed. In terms of periodontal health, 75% of the 35–44-year-old cohort had periodontal pocketing, 13% of which were classified deep pockets. These data suggest that the burden of maintenance of heavily restored dentitions will remain a major requirement for the dental profession.

A further factor to consider is the attendance pattern of adults, and their attitudes to dental care. At the present time, significant proportions of adults do not attend the dentist regularly, and only attend when in pain or when they need emergency treatment. Barriers to the uptake of dental care include cost, fear of dental procedures and negative images of the dental practice environment. It seems likely that many in this group of adults will remain a “hard core” of non-attenders, and are unlikely to remain dentate throughout their lifetime.

The attitude to tooth loss is also changing. Greater numbers of adults are reporting that they find the thought of losing their teeth upsetting and are likely to seek treatment to retain some of their natural teeth. Owing to the high prevalence of dental disease in the older-age cohorts, many will not achieve their aim of being dentate for life. Consequently, the loss of natural teeth will, for some, occur late in life at a time when denture control skills are difficult to acquire.

The attitudes to edentulousness, and satisfaction with complete dentures will, in the future, be influenced by current trends in adult dental health. As the proportion of adults retaining teeth into old age increases, the transition to the edentulous state will, for some, occur later in life. As the ability to learn the complex series of reflexes required to control complete dentures diminishes with age, it seems possible that denture-wearing complaints may increase in the elderly age groups.

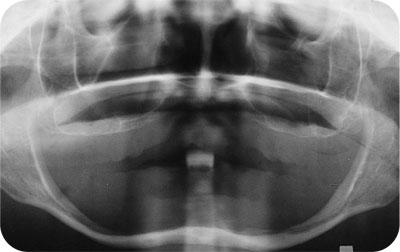

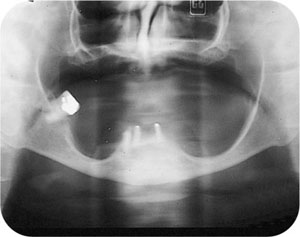

The anatomical changes which occur following extraction of natural teeth can broadly be divided into intraoral and extraoral changes. These will differ between individuals who remain partially dentate and those who are edentulous following tooth loss. As people age, loss of alveolar bone is inevitable. However, following total tooth loss, alveolar bone resorption is greatly increased. Alveolar bone height and width decrease markedly (Figs. 1-1 and 1-2). Most of this change occurs in the first year following extractions, but remains an inexorable process throughout life. Resorption occurs on the buccal aspect of the maxillary ridge and the lingual aspect of the mandibular ridge. In a mixed longitudinal study over 25 years, Tallgren demonstrated the extent of bone loss in edentulous individuals. She demonstrated that the loss of bone is four times greater in the mandible than the maxilla. Despite extensive research, the reason for great individual variation in bone loss remains unclear. It seems likely that a combination of local and systemic factors may be responsible for this phenomenon.

Fig 1-1 Orthopantomogram showing the edentulous jaws of a 62-year-old female. Note how thin the lower jaw is following extensive loss of alveolar bone.

Fig 1-2 Orthopantomogram of 75-year-old female with retained dental roots in the anterior mandible. Note the bone height around teeth compared to edentate areas in the lower jaw.

As well as anatomical changes, further consequences of tooth loss include:

impaired mastication

limitation of food selection, especially nutritious foods such as fruit and vegetables

speech impairment

appearance change

psychosocial impact.

The influence of tooth loss on masticatory ability, performance and dietary selection has been well documented. Objective tests of masticatory performance indicate that chewing efficiency of edentulous adults is approximately 20% that of a dentate individual.

Subjective tests that assess patients’ attitudes to food choice suggest that edentulous patients tend to favour highly flavoured soft foods that are of low nutritional value. Reasons for this are complex, and include socio-economic factors as well as denture-related causes. Surveys of nutritional intake, report that edentulous adults have lower intake of fibre, vitamin C and other important nutrients, compared with dentate adults. This suggests that edentulous patients with poor-quality diet are at a higher risk of serious illness, including cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Loss of anterior teeth affects speech and can be a difficult problem to deal with, particularly in patients with a skeletal Class 2 jaw relationship.

In addition to preserving bone, teeth support soft tissues such as the cheeks and lips. This in turn has an influence on appearance, and appearance is adversely affected once teeth are lost. This is most noticeable in the circumoral region, as the commisures of the lips collapse inward. A further consequence is loss of vertical dimension and this has the affect of approximating the nose to the chin (Fig 1-3). Complete replacement dentures can rectify some of these changes, but there are limitations. In cases of severe resorption, it may be impossible to meet the patient’s aesthetic requirements and at the same time provide stable replacement dentures.

Fig 1-3 Appearance of edentulous patient. Note loss of vertical dimension and resultant proximity of chin to nose.

Increasingly, researchers are beginning to look at wider issues of health-related quality of life