Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Introduction

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Why Indirect Restorations?

Why do Indirect Restorations Fail?

Dental Caries

Treatment Planning – Stabilisation and Prevention

Stepwise Excavation

Caries Prevention

Definitive Restorations

Periodontal Disease

Endodontic Failure

Preoperative Assessment – Vitality Testing

Restorative History of the Tooth

Aesthetic Failure

Mechanical Failure

Loss of Retention

Catastrophic Fracture or Failure of Dental Material

Wear

Fracture

Further Reading

Chapter 2 Indications for Crowns

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Replacement Crowns

Endodontically Treated Teeth

Tooth Wear

Broken Down Teeth

Appearance

Cracked Teeth

Realignment of the Occlusal Plane

Further Reading

Chapter 3 Retention of Cores

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Vital Teeth

Dentine Adhesives

Composite Cores

Glass-ionomer Cores

Amalgam Cores

Slots and Grooves

Dentine Pins

Pin Types

Non-vital and Endodontically Treated Teeth

Posterior Teeth

Anterior and Single Rooted Teeth

Post Space Preparation

Choice of Post

Choice of Core Material

Further Reading

Chapter 4 Choosing the Right Crown

Aim

Objective

Introduction

General Factors

Preoperative Factors

Tooth Related Factors

The Size of Restoration

The Margin

The Core

Vertical Space

Horizontal/Labial Space

Occlusal Load

Technical Skill

Selecting the Appropriate Crown

Materials

Metals

Ceramics

CAD/CAM

CAD/CAM without coping, e.g. Cerec III (Sirona, Germany)

Castable

Conventional

Shell Crowns (Resin Bonded/Dentine Bonded Crowns)

Clinical Indications

Colour Matching

Shade Taking

Tooth Shape

Length and Width

Position of the Gingival Margin

Incisal Edge

Lips

Contact Areas

Surface Finish of Crowns

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Tooth Preparation

Aim

Objective

Cemented Crowns

Burs

Requirements

Extracoronal Restorations

Stages in Crown Preparation

Occlusal/Incisal Reduction

Buccal/Lingual Reduction

Proximal Surfaces

Differences between Crowns

Metal-ceramic Crown

All-ceramic Crowns

Three-quarter Crown

Cuspal Coverage Overlay

Intracoronal Restorations

Metal Inlays

Porcelain Inlays

Indirect Composite Inlays

Methods to Increase Retention

Slots and Grooves

Resin-retained Indirect Restorations

Summary

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Shade Taking, Provisional Crowns, Impressions and Cementation

Aim

Objective

Introduction

Shade Taking

Provisional Crown

Matrices

Single Units

Wax matrix

Silicone matrix

Alginate matrix

Preformed crowns

Other techniques

Multiple Units

Cementing of the Provisional Restorations

Tissue Control

Subgingival Preparations

Impressions

Impression Materials

Choice of Tray

Bonnets

Interocclusal Records

Fitting Crowns

Polishing the Crown

Final Cementation

Choice of Cement

Types of Luting Cement

Zinc Oxide and Eugenol

Zinc Phosphate

Zinc Polycarboxylate

Glass-ionomers

Resin-modified Glass-ionomer

Resin-based Luting Cements

Summary Stages in Crown Preparations

Single Restorations Without the Need for a Diagnostic Wax-up

Multiple Restorations with Diagnostic Wax-ups

Cementation of Definitive Crowns

Chapter 7 Managing the Occlusion

Aim

Objective

Introduction

Intercuspal Position (ICP)

Occlusal Vertical Dimension

Stable Occlusion

Terminal Hinge Axis and Retruded Contact Position (RCP)

Lateral Excursions

Working Side

Non-working Side

Canine Guidance

Restoring the Canine

Restoring Posterior Teeth

Group Function

Difficulties

Anterior Guidance

Reproducing Anterior and Canine Guidance (Fig 7-11a–g)

Conformative vs. Reorganised Approach

Further Reading

Chapter 8 Short Clinical Crowns

Aim

Objectives

Introduction

Single Teeth

Trauma

Replacement Crowns

Loss of Crown and Overeruption of Teeth

Multiple Crowns

Causes of Erosion

Prevention

Management

Localised Tooth Wear

Partially Dentate Patient

Generalised Tooth Wear

Acrylic Splints

Composite Build-ups

Summary

Management of Tooth Wear

Localised Tooth Wear

Generalised Tooth Wear

Further Reading

Chapter 9 When and How to Articulate

Aim

Objective

Introduction

Occlusal Adjustment

Number of Teeth Being Restored

Reorganising the Occlusion

Types of Articulator

Simple Hinge

Average Value

Semiadjustable Articulators

Fully Adjustable Articulators (Fig 9-8a–c)

Facebows

Interocclusal Records

Terminal Hinge Axis Record

Intercuspal Record

Setting the Condylar Inclination

Bennett Settings

Interocclusal Records

Checking the Occlusion

Further Reading

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 25

Operative Dentistry – 3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Bartlett, David

Indirect restorations. - (Quintessentials of dental practice; v. 25)

1. Crowns (Dentistry)

I. Title II. Ricketts, David III. Wilson, Nairn H.F.

617.6’922

ISBN: 1850973016

Copyright © 2007 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 1-85097-301-6

The successful provision of indirect restrictions is demanding. A diversity of skills, knowledge and experience are required to consistently succeed in this important aspect of clinical practice. Mediocrity in indirect restorations is tantamount to inviting early failure, with the risk of substantial damage to the remaining tooth tissues and the dentition.

Interestingly, failure is the starting point of this latest addition to the Quintessentials series – most indirect restorations replacing failed restorations. Against this backdrop, the authors take the reader through the indications and the many, varied intricacies integral to the provision of successful indirect restorations. The text, as has come to be expected of new volumes in the popular Quintessentials series, is generously illustrated and peppered with invaluable tips and guidance, tempered by the authors’ special interests and expertise in the field.

As indicated by the authors in their Preface, this book is not intended to be a comprehensive tome; it is a succinct text highlighting key considerations, knowledge and understanding for the busy practitioner, let alone the student wishing to avoid information overload. Once read, this book should not be put aside, but placed together with other Quintessentials volumes and similar books for ready reference and guidance.

Hopefully, this book will give clinicians new insight and pointers to enhanced success, if not excellence in indirect restorations. This is a handsome, easy-to-read book, promoting a modern evidence-based approach to indirect restorations.

Congratulations to the authors for a job well done.

Nairn Wilson

Editor-in-Chief

This book is written to guide practitioners and students in the restoration of teeth by means of indirect restorations. Many well written textbooks on this subject already exist. This volume is not intended to be a definitive work; by contrast, it is an overview of key points and issues critical to success with indirect restorations. We have not included conventional and minimal preparation bridgework as there are other books in the Quintessentials series covering these topics. But many of the principles in this book can be applied to these areas.

On reading this book the reader will be able to:

Plan indirect restorations taking into consideration the importance of previous caries experience. The reasons for placing indirect restorations will be reappraised.

Consider and review the indications for indirect full and partial coverage crowns.

Appreciate how to place reliable and retentive cores.

Consider what factors are important when choosing the type of crown and how to select the best materials to use.

The book also:

Describes the common tooth preparations for crowns and assesses how to achieve the best result.

Describes how to take a shade, make provisional restorations, record impressions and explains the value of taking interocclusal records.

Considers aspects of occlusion and explains the relevance of occlusal consideration in the provision of indirect restorations.

Reviews the problems associated with short clinical crowns and how to manage them.

Describes when and how to use an articulator.

David Bartlett and David Ricketts

London and Dundee

David Ricketts would like to express his gratitude to Catherine Burnett for her assistance with the photography in this book.

Both authors would also like to acknowledge the laboratory technicians who made the crowns illustrated in this book.

To familiarise the reader with planning indirect restorations, taking into consideration the importance of previous dental history. The reasons for placing indirect restorations are reappraised.

On reading this chapter the reader will better understand the importance of prevention and maintaining pulp and periodontal health in the provision of successful indirect restorations.

To the reader, it may seem strange that a text on successful indirect restorations should begin with a chapter discussing failures. But in terms of success, it is probably the most important subject as many indirect restorations are replacement restorations. The restorative cycle, once established, will continue unless lessons are learnt from failure events. This chapter will consider the:

failure of direct and indirect restorations

maintenance of pulp health

importance of periodontal health

importance of pulp vitality.

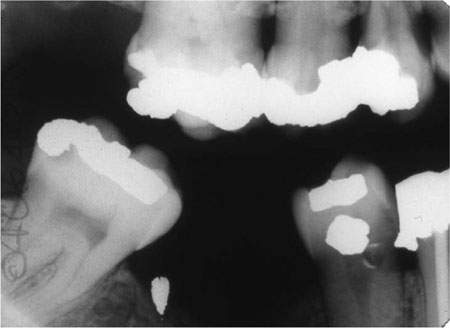

Most indirect restorations are placed to restore the contour, function and appearance of teeth previously restored with plastic restorations. In restoring broken down or damaged teeth with plastic restorations, it is sometimes difficult to achieve appropriate contact areas (Fig 1-1) and occlusal form (Fig 1-2). Indirect restorations such as crowns, onlays and inlays enable the contact areas and the occlusal form to be controlled in the laboratory. The majority of extensive restorations are placed because of primary caries, or caries adjacent to existing restorations. Others will be placed following a fracture of tooth tissue, classically a cusp fracture associated with an occlusoproximal restoration (Fig 1-3). Relatively few extensive restorations are placed as a consequence of trauma.

Fig 1-1 Bitewing radiograph showing a ledge on the amalgam restoration in the LR4. This occurred as the LR4 has an extensive defect, making it difficult to develop a tight contact area while keeping the matrix band adapted cervically.

Fig 1-2 Given the extent of this cavity, it is difficult to place an amalgam restoration with adequate occlusal contour.

Fig 1-3 The MOD restoration in this lower molar tooth, although not large, has weakened the tooth and the lingual cusp has fractured.

Studies on the failure of indirect restorations indicate that the commonest cause of failure is secondary caries as diagnosed clinically. Other causes include various forms of mechanical breakdown and failure, together with unacceptable appearance and endodontic and periodontic complications.

Caries remains the most important disease that affects teeth. It is responsible for most directly placed restorations and their subsequent replacements. Ultimately, when direct restorations are contraindicated, indirect restorations are required, but typically these will not be permanent and will fail because of caries. This is ironic given that dental caries is a preventable disease.

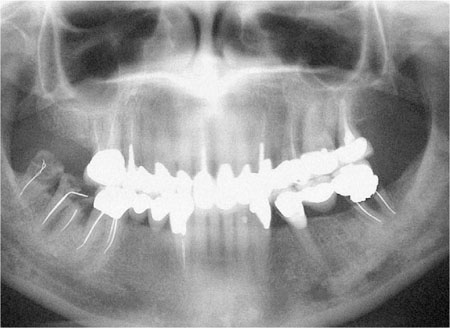

Failures such as those illustrated in Fig 1-4 are preventable. It is important that we learn from such failures, by ensuring that operative dentistry is preventively driven.

Fig 1-4 Dental panoramic tomogram of a patient with an extensively restored dentition; including multiple indirect restorations. Failure of many of the restorations has been caused by caries, some have been lost (LR7 and 8), and some have been repaired (LL5).

Before placing indirect restorations, it is important that the patient’s caries risk is assessed. Only patients with a low caries risk should be prescribed indirect restorations. Some of the more important caries risk factors are included in Table 1-1.

| Low caries risk | High caries risk |

| Minimally restored dentition | Heavily restored dentition |

| No history of replacement restorations | History of frequent restoration and re-restoration |

| Good oral hygiene | Poor oral hygiene |

| Exposure to topical fluoride in water, toothpaste or mouthwash | No exposure to topical fluoride |

| Diet: low frequency of sugar intake | Diet: frequent consumption of sugar |

| High socio-economic status | Low socio-economic status |

| No new carious lesions | Presence of new carious lesions |

For a patient with new and secondary caries (Fig 1-5a,b) it is important that treatment is carried out in phases. The first phase should address pain and other immediate problems. Thereafter, care should be aimed at prevention. This stage of treatment should include stabilisation of the lesions and protection with temporary and transitional restorations. This is necessary to ensure that extensive lesions do not progress during the preventive phase of treatment. It also allows a stepwise approach to caries removal.

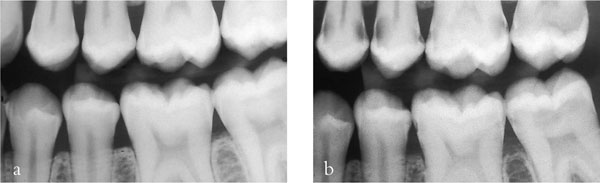

Fig 1-5 (a,b) A left bitewing radiograph of an 18-year-old patient (a), and four years later (b). This demonstrates that caries risk can change and the dentist should always be vigilant and continually assess risk. This patient’s initial treatment should be pain relief, followed by a stabilisation phase and prevention. Indirect restorations should not be considered until successful prevention has been instituted and caries risk has been controlled.

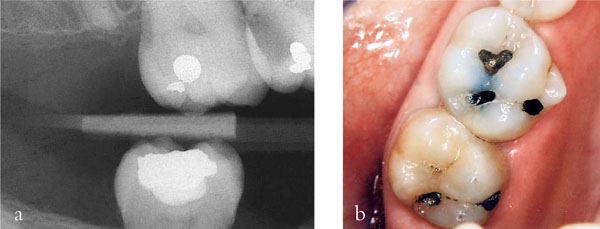

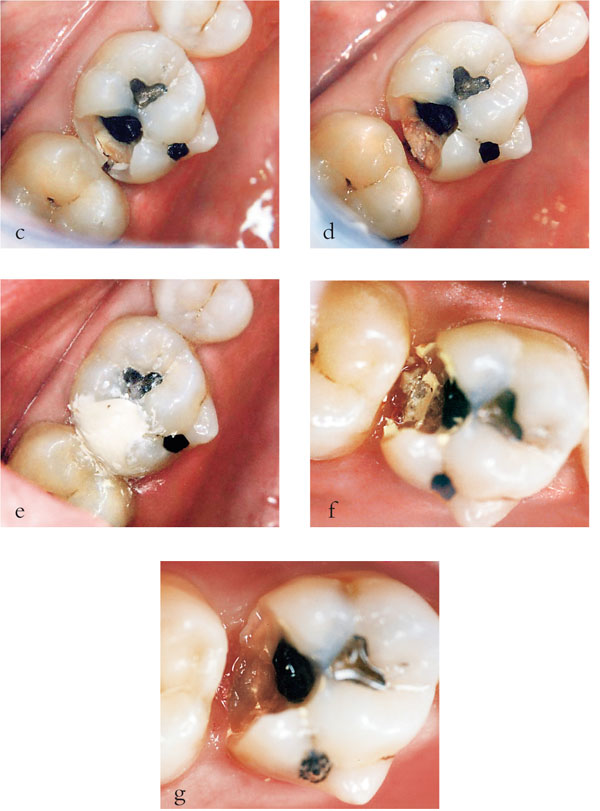

In the tooth of a young patient with a relatively large pulp and a deep carious cavity, the risk of pulpal exposure during tooth preparation is high (Fig 1-6a–g). To avoid this, a stepwise approach to caries removal should be adopted, providing there are no signs or symptoms of pulpal pathology. Assessment should include a vitality or sensitivity test and a periapical radiograph of the tooth to ascertain if periradicular pathology is present.

Fig 1-6 (a,b) A radiograph (a) and clinical appearance (b) of an extensive carious lesion on the distal aspect of the UR6 of a young teenage patient. In such a situation complete caries removal in one visit risks exposing the pulp. Stepwise excavation reduces this risk.

Fig 1-6 (c–g) In this procedure, access to the caries was gained (c) at the first appointment and peripheral caries removed leaving soft carious dentine pulpally (d). A provisional restoration was placed, using a polycarboxylate cement (e) and then left for 6 to 12 months. When the restoration was removed (f) and pulpal caries excavated no pulpal exposure occurred (g) (Series of images courtesy of Dr Nicola Innes).

During the initial stabilisation phase of treatment, access to carious dentine should be gained and peripheral caries at the enamel-dentine junction removed. This leaves soft carious dentine over the pulp, some of which can be excavated. This is then covered with a setting calcium hydroxide lining material and the tooth restored with a composite, glass-ionomer or polycarboxylate cement provisional restoration. This provisional restoration should be left for six to twelve months, during which time bacteria within the lesion will become less metabolically active and reduce in number. This is because the intraoral source of sugar substrate has been blocked by the restoration, assuming a good peripheral seal. As the bacteria become less active, the lesion activity slows and may even stop, allowing time for pulp-dentine complex reactions to occur, in particular tubular sclerosis and reactionary dentine formation. When the six to twelve months has elapsed, reentry into the lesion allows further caries removal with a significantly reduced risk of pulpal exposure. This second stage of caries removal is best carried out when the patient is complying with dietary advice, and oral hygiene instruction has been shown to be satisfactory.

The preventive aspect of treatment should include disclosing of the teeth and oral hygiene instruction (Fig 1-7a,b). Plaque scores may be useful to demonstrate problem areas to the patient and to monitor patient compliance. Diet diaries should be filled in by the patient for three consecutive days, including two work days and one leisure day. This will allow cariogenic elements of the diet to be identified, including frequency of sugar intakes. Once these aspects of the diet have been highlighted in the diet diary, effective dietary advice can be given and topical fluoride should be prescribed.

Fig 1-7 (a,b) Disclosing plaque allows plaque scores to be recorded. Monitoring oral hygiene over time allows patients to appreciate the association between the bacterial biofilm and the resultant caries when the plaque is partially (a) and completely removed (b).

Once caries has been stabilised the next phase of the treatment can be considered, including decisions as to which teeth should be restored. Some teeth may need extraction or root canal treatment. Initially, temporary restorations should be replaced with simple restorations. Before considering costly and time consuming indirect restorations, further assessment is required to ensure compliance with oral hygiene procedures and to assess caries activity. In this way, the success of primary preventive measures are reassessed, and only if they have been successful should indirect restorations be considered. If in doubt, further preventive advice is indicated, together with repeat follow-up reviews. Failure to do this is likely to result in a disastrous outcome as illustrated in Fig 1-4.

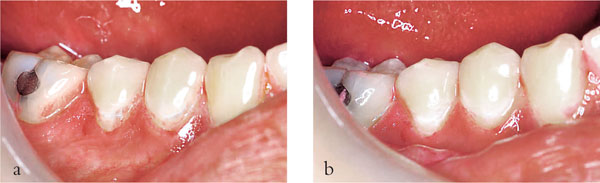

Indirect restorations can fail as a result of periodontal disease. This can occur as a consequence of poor primary prevention prior to the placement of restorations. Aggravating factors such as overhanging margins and overcontoured crowns can lead to secondary failure. The patient in Fig 1-8 illustrates both of these points. Failure to establish good periodontal health prior to preparing the upper incisor teeth for crowns led to further attachment loss and recession. This was exacerbated by deficient crown margins. Successful periodontal treatment led to resolution of inflammation, further recession and the need for crown replacement to improve the appearance of the teeth.

Fig 1-8 Gingival recession around upper incisor teeth following successful periodontal treatment subsequent to the placement of the crowns.

A basic periodontal examination (BPE) should be carried out as part of the initial assessment. The examination is carried out by dividing the mouth into sextants: upper and lower left and right posterior; upper and lower anterior. A standard periodontal probe with a 0.5 mm ball end and a colour coded band from 3.5 to 5.5 mm should be used. The periodontal probe is “walked” around each tooth, examining at least six sites per tooth. For each sextant the highest score is recorded (Table 1-2).

| Periodontal (BPE) score | Definition | Suggested treatment |

| 0 | Healthy gingival tissue. No bleeding after gentle probing | No treatment |

| 1 | Coloured part of probe completely visible. No calculus or defective margins. Bleeding after gentle probing | Oral hygiene instruction only |

| 2 | Coloured part of probe completely visible. Supragingival calculus or defective margin of restoration | Oral hygiene instruction. Removal of calculus and correction of defective margins. Review in one year |

| 3 | Coloured part of probe enters periodontal pocket but remains partially visible | As for Code 2 but more time required. Plaque and bleeding scores at start and end of treatment. Probing depths at end of treatment. Repeat records after one year or less |

| 4 | Coloured part of probe completely disappears into pocket – probing depth ≥6 mm | Full probing depth chart (6 point pocket chart) required + gingival recession + furcation + intraoral radiograph of relevant

teeth. As for 2. Root planing pockets >4 mm. Reexamine to assess results of periodontal treatment and whether further treatment required, possibly periodontal surgery |

| 4* | * denotes furcation involvement and/or attachment loss >7 mm | * Specialist care required |

Indirect restorations should not be considered until the treatment in Table 1-2 has been carried out, reevaluated and found to be successful. There should be no signs of active periodontal disease in relation to the tooth being restored, such as bleeding on probing. Even gingival bleeding with a BPE score of 1 will make impression taking difficult and the resulting restoration is likely to have a poor fit. Consequently more plaque accumulation occurs and the disease process is perpetuated. Additionally, gingival inflammation at the time of placement will lead to bleeding and excess gingival crevicular fluid, which may compromise the cement lute. This predisposes to sensitivity, secondary caries and staining around tooth coloured restorations, including all-ceramic crowns and veneers (Fig 1-9).

Fig 1-9 Poor gingival health at the time of placement of these composite vaneers compromised bonding leading to microleakage and staining of the restoration margins.

If a new crown is required to replace an existing crown with a ledge or secondary caries, removal and initial replacement with a good fitting provisional restoration is necessary. This allows gingival health to be maintained prior to the definitive restoration. This is particularly important in relation to anterior teeth as resolution of gingival inflammation, let alone periodontal disease, typically leads to shrinkage of the tissues, exposing the crown margins. A definitive crown placed prior to resolving gingival and periodontal problems will lead to an unpredictable crown to gingival margin relationship.

It is not uncommon to find evidence of periradicular pathology associated with teeth that have been crowned and from abutments for conventional bridgework. This may arise as a result of inadequate preoperative assessment, or as a direct consequence of the operative procedure.

Prior to considering an indirect restoration for a vital tooth, preoperative assessment should include testing of pulp vitality. Pulp vitality refers to a patent blood supply to a tooth. This can only be indirectly assessed by determining the neuronal response to various stimuli, thus the term sensitivity testing is considered more appropriate. For teeth that have not been treated endodontically, this can conveniently be carried out by determining the pulpal response to thermal and electrical stimuli.

It is important when sensitivity tests are carried out that the tooth in question is isolated with cotton wool rolls and dried. This is particularly important when an electric pulp tester is used, as surface conduction in saliva to the gingival margin or adjacent teeth can lead to a false positive response. False positive responses can also be obtained in patients that are anxious with a heightened awareness and anticipation of pain and in multirooted teeth in which one or more canals may contain necrotic pulp tissue. After a tooth loses its blood supply and becomes non vital, C nerve fibres may remain capable of responding to stimuli for some time giving rise to a false positive response.

Likewise false negative responses are possible. Teeth in elderly patients and teeth which have been extensively restored may have significant deposits of normal physiological secondary dentine or tertiary dentine formation respectively giving a protective “insulating” effect. Following trauma a tooth may be concussed and whilst having a patent blood supply may not respond to stimuli for some time. Some patients’ pain threshold may be high and they experience no pain from such stimuli.

The results of vitality or sensitivity testing can be unreliable and, as such, the results should not be taken in isolation. Other similarly sized and restored teeth should also be tested for comparisons and other tests such as percussion tests, a pain history and radiographic appearance should also be taken into account.