Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Smile Dimensions

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Tooth Size

The Golden Proportion

Gingival Position

Black Triangles

Lip Line

Masking Gingival Tissues

Moral Issues

Further Reading

Chapter 2 Shade and Colour

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Shade-Matching

Tips for Choosing the Right Shade

Pixels v. Rods and Cones

Further Reading

Chapter 3 Bleaching and Microabrasion

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Common Causes of Tooth Discoloration

Localised

Trauma:

Superficial staining:

Generalised

Acquired:

Hereditary:

Trauma

Superficial staining

Age-related changes

Tetracycline

Fluorosis

Hereditary causes

Vital Bleaching

Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

Mode of action

Carbamide Peroxide

Safety

Effects on Teeth and Restorative Materials

Stability of Bleaching

Preservation of Tooth Tissue

Side-effects

Indications

Contraindications

Advantages

Disadvantages

Clinical Technique

Review Appointments

Non-Vital Bleaching

Case Selection

Sodium Perborate

Side-effects

Technique

Advantages

Side-effects

Combination Techniques

In-Surgery Techniques

Case Selection

Clinical Stages

Other Bleaching Techniques

Whitening Strips™

Topically Applied Systems

Whitening Toothpastes

Microabrasion

Clinical Stages

Further Reading

Chapter 4 Laminate Resin Composite Techniques

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Advantages of Directly Placed Resin Composites

Disadvantages of Directly Placed Resin Composites

Clinical Techniques

Small and Moderately Sized Restorations

Clinical Stages

Changes to Shape and Size of Teeth

Polishing

Clinical Stages

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Porcelain Laminate Techniques

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Historical Perspective

Indications

Contraindications

Advantages

Disadvantages

To Prepare or Not to Prepare?

Tooth Preparation

Bur Selection

Other Clinical Procedures

Luting Procedures

Finishing Procedures

Maintenance Procedures

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Technical and Laboratory Considerations

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Technical Considerations for Full Coverage Restorations

Metal Ceramic Crowns

All-Ceramic Crowns

Tooth Preparation

Stages of Tooth Preparation

All-Ceramic Crowns

CAD/CAM-Produced Coping with Conventional Build-up

CAD/CAM without Coping

Pressed Ceramics

Conventional Build-up with Alumina Coping

Metal Ceramic Crowns

Provisional Crowns

Soft-Tissue Management

Impression Materials

Clinical Stages for the Resin Replica Technique

Conformative Approach

Reorganised Approach

Further Reading

Chapter 7 Aesthetic Compromises and Dilemmas

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Informed Consent

The Single Tooth

Doing Nothing

Bleaching

Microabrasion With and Without Bleaching

Crowning or Veneering the Tooth

Porcelain Laminate Veneers

General Failure During Clinical Service

Complete Loss

Marginal Inflammation

Bulky Laminates

Peeling of Laminate

White Flecks Under Laminate Surface

Marginal Staining

Incisal Angle or Edge Fracture

Resin-Composite Laminate Techniques

Staining of Entire Laminate

Wear of the Labial Surface

Fracture of Crowns and Bridgework

Intraoral Repair of Fractured Crowns and Bridgework

Repair Materials

Further Reading

Appendix

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 19

Operative Dentistry – 2

British Library Cataloguing-in Publication Data

Bartlett, David

Aesthetic dentistry - (Quintessential of dental practice; 19. Operative dentistry; 2)

1. Dentistry - Aesthetic aspects

I. Title II. Brunton, Paul A. III. Wilson, Nairn H. F.

617.6

ISBN 1850973040

Copyright © 2005 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 1-85097-304-0

Aesthetic dentistry continues to grow exponentially in modern clinical practice. Patients now expect and greatly value dental attractiveness as one of the principal outcomes of routine dental care. Realising this goal can, however, be challenging. Enhancing a pleasing smile, let alone the successful management of unsightly teeth, by means that will withstand the rigours of the oral environment, demands skilful application of the art and science of both traditional and state-of-the-art dentistry, underpinned by knowledge and understanding of the many varied factors that influence the appearance of teeth individually and collectively. This is the complex subject area addressed in this excellent addition to the Quintessentials of Dental Practice series.

In common with all the other books in the series, Aesthetic Dentistry focuses on the essence of the subject matter, with high-quality illustrations distributed liberally throughout the text to highlight principles, key points, critical techniques and common pitfalls. Given the importance aesthetic dentistry has now assumed in present-day clinical practice, which is no longer limited to the three “Rs” – “repair, removal and replacement” – the information and guidance included in this book should be viewed as fundamental to the everyday business of dentistry.

As with most things in the clinical practice of dentistry, good clinical outcomes are down to trust and understanding between dentist and patient, effective communication, up-to-date knowledge, careful planning and meticulous detail in the execution of operative procedures. Good aesthetic dentistry is not easy; it is typically very demanding. This book provides a most valuable aid to meeting these demands – an excellent investment for practitioners and students with patients who would welcome an improvement in their dental appearance.

Nairn Wilson

Editor-in-Chief

This book is not meant to be a definitive textbook on aesthetic dentistry. There are already several comprehensive texts available on the subject. This book, by way of contrast, is designed to be an aide-mémoire for success, providing tips and hints for practitioners to improve their practice of everyday aesthetic techniques, coupled with a description of the underlying theory. The text will not consider single-unit indirect restorations other than certain aspects from an aesthetic point of view. Readers are referred to a specific text that considers indirect restorations in some detail. In addition, an appendix is included, which lists materials and instruments the authors have found useful.

On reading this book the reader will be able to:

appreciate the composition and variations in the smile

understand the theory of colour and how this affects shade-taking and colour communication

select suitable cases for vital and non-vital bleaching

consider the use of microabrasion to remove unsightly or unaesthetic surface defects

apply resin composites for successful anterior laminate restorations

prescribe successfully porcelain laminate veneers

understand how technical, laboratory and periodontal factors can affect aesthetics

minimise aesthetic compromises

solve common aesthetic dilemmas.

David Bartlett

Paul A Brunton

London and Manchester, March 2005

The authors would like to thank Dr David Ricketts for reviewing and providing valuable feedback for the entire manuscript and Miss Selina Priestley for reviewing Chapter 2.

The authors are also indebted to the following individuals who have generously provided illustrations, which made the publication of this book possible: Miss Leean Morrow for the use of Figs 1-6 to 1-7 and 7-6; David Leedham for the use of Figs 2-7 to 2-9; and Tim Horwood for the use of Figs 4-5, 4-6, 5-5 and 6-5. Figs 6-4, 6-6 and 7-3 are reproduced from Dental Update by permission of George Warman Publications (UK) Ltd. Fig 6-1 is reproduced by permission of the British Dental Journal.

To practise successful aesthetic dentistry it is important to be familiar with the essential components of an “ideal” smile – remembering of course that the “ideal” smile is a concept around which all patient treatment is based and that every patient requires an individual approach. The aim of this chapter is to acquaint practitioners with the dimensions and components of an “ideal” smile.

On reading this chapter practitioners will be able to assess the shape and inter-relationship of crowns and restorations within the framework of a patient’s individual smile.

Aesthetics can be viewed at two levels – the conversational and tooth levels. The conversational level considers the arrangement of teeth within the framework of a face and an individual’s smile. The tooth level is the consideration of everything that makes a tooth look like a tooth. It is important that teeth should look like teeth, but equally it is important that teeth are appropriately framed. To do this effectively a practitioner must be familiar with the dimensions of a smile, to include consideration of the following:

tooth size

the golden proportion

gingival position

black triangles

lip line

masking gingival tissues

moral issues.

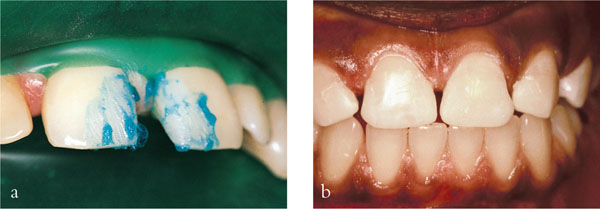

On average, the width of an upper incisor tooth is 75% of its length and where this is not the case the result is generally unaesthetic (Fig 1-1). The perception of tooth shape, however, is very personal. For instance, someone with narrow teeth and diastemas might be quite content with their appearance. But if the patient found the appearance unacceptable and new crowns were planned for the upper incisors, it may be worthwhile to consider using this rule (width based on 75% of length) to calculate tooth width. Before any changes to width and length are embarked upon, it is essential that a diagnostic wax-up is used to assess the proposed changes to a patient’s appearance. If necessary, directly placed resin composites can be used either for the short or medium term to assess the final appearance of the teeth before proceeding to the definitive treatment (Fig 1-2). The aesthetics of present-day resin composite often make the definitive stage of treatment unnecessary.

Fig 1-1 (a) Unaesthetic crowns where the width and length of the crowns are equal. (b) Replacement crown of appropriate dimensions.

Fig 1-2 (a) Etch placed to reduce a diastema with resin composite in a young patient. (b) Post-treatment reduced diastema.

The width-to-length ratio influences the judgement to close diastemas. If the ratio of the tooth is above 75% then widening the tooth further to reduce the space may produce an appearance that is unacceptable. The compromise and closure might be acceptable for a narrow tooth that could easily be widened, but for a broader tooth other factors may need to be considered. In such cases the location of the gingival tissues down the length of the crown is another assessment that is important.

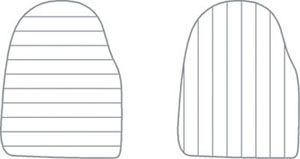

Traditionally, some clinicians have linked tooth shape with gender. Narrower teeth may be found in females, broader ones in males. This demarcation is by no means accurate, and when bridgework or indirect restorations are planned clinicians normally have the advantage of other standing teeth to guide decisions on the shape and contour of the restoration. There are various technical tricks that can be adopted to hide or attenuate the angles of laboratory-made crowns. Mid-line horizontal lines appear to shorten the crown, while vertical ones nearer the proximal angles would broaden it (Fig 1-3). Additionally, if the space is too wide an illusion can be created by introducing sharp angles away from the proximal surface to make the crown appear narrower (Fig 1-4).

Fig 1-3 Horizontal lines make the identical crown appear shorter than the crown with the vertical lines.

Fig 1-4 A rounded or smooth contact region can make the crown appear broader, but for one that is too broad making a more pronounced angle just away from the contact point creates the illusion of a narrower crown.

The most important criterion in making a judgement on aesthetics is the patient. The perceptions of colour and shape are somewhat age-related. Senior patients commonly perceive bigger and brighter teeth as indicative of youth. Unfortunately, there is an increasing trend to achieve brighter and whiter teeth producing shades that are lighter than B1. The result for many practitioners is too artificial, but increasingly patients expect and demand shades at this end of the spectrum. If such a shade is contemplated, considerable discussion should occur preoperatively and the patient should be given a clear idea what the shade is likely to look like within the parameters of their individual smile.

Normally lateral incisors are smaller than centrals, and if their comparative size starts to become equal the result can be aesthetically unacceptable. The golden proportion adopts this concept with a balance between the canines, laterals and central incisors. The golden proportion was formulated as one of Euclid’s elements c. 300 BC and it applies to dental aesthetics. This is amply illustrated by the fact that the central incisors are in golden proportion to the lateral incisors, which in turn are in golden proportion to the canines (Fig 1-5). Put simply, the central incisor is 1.618 wider than the lateral incisor. It is possible using grids that are based on the width of the central incisor to determine the width of a patient’s smile. It is important to recognise that the proportion of the smaller to the greater – for example, the width of the central incisor in relation to the width of the lateral incisor – is golden but so also is the width of the central incisor in relation to the combined widths of the two teeth. It is accepted that when teeth are set up so that the proportion is golden within the confines of the smile it is aesthetically pleasing.

Fig 1-5 Teeth in golden proportion.

The width of a patient’s smile is in golden proportion to the rest of the face. Upon smiling the anterior aesthetic segment is framed by the lips and there is space between the teeth and the corners of the mouth. This neutral space is all too often filled with over-contoured teeth or dental arches that have been made too wide. If this neutral space is lost the smile is not aesthetically pleasing. The width of the anterior aesthetic segment is in golden proportion to the width of the smile, ideally with the midline coincidental with the midline of the face.

The gingival position on the upper lateral incisors in a healthy state is closer to the occlusal plane than on the central incisors and canines. Either naturally, or as a result of tooth wear and dentoalveolar compensation, this position may alter and result in the lateral incisors having a similar height to the incisors. The unworn step effect produces a natural and pleasing appearance and can accentuate the dominance of the upper central incisors, providing an acceptable aesthetic result (Fig 1-6). Whether it is acceptable to undertake crown lengthening surgery to produce this step height appearance is doubtful but if, for instance, surgery was planned as part of the treatment for tooth wear, placing this step in the gingival position is worth considering.

Fig 1-6 (a) Unaesthetic crowns with unequal gingival heights and teeth in incorrect proportion to each other. (b) New crowns provided for the patient after crown lengthening surgery.

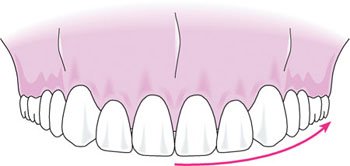

The location of the gingival margin needs to be symmetrical. Unilateral gingival recession may not create a clinical problem if the patient has a low lip line. But in someone with a high lip line, unequal gingival contours may compromise the appearance of the anterior teeth (Fig 1-7). Surgical procedures aimed at adjusting the gingival position are, however, outside the remit of this book and readers are referred to a specialist textbook in periodontics. This problem, however, should be considered at the treatment-planning stage and help sought from a periodontist, if appropriate.

Fig 1-7 Unequal gingival contours.