Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 A Whistle-Stop Tour of the Periodontium

Aim

Outcome

Terminology and Orientation

The Gingivae

The Gingival Epithelium

The Gingival Connective Tissues

The Periodontal Attachment Apparatus

Root cementum

PDL

Alveolar bone

Further Reading

Chapter 2 How Does Plaque Cause Disease?

Aim

Outcome

A Model for Periodontal Disease Pathogenesis

How Do Bacteria Cause Disease?

Maturation of the Plaque Biofilm

Microbial Invasion

Which Organisms Cause Periodontal Diseases?

The specific plaque hypothesis

The non-specific plaque hypothesis

The environmental plaque hypothesis

Stratification of Organisms Within the Pocket and Cluster Analysis

Conclusions of Clinical Importance

Further Reading

Chapter 3 The Role of the Host Response

Aim

Outcome

Innate Immunity

Epithelial Barriers

Fluid Lubrication

Complement Cascade

Cell-signalling Molecules

Vasoactive Peptides

Adhesion Molecules

The Polymorphonuclear Leucocyte (or Neutrophil/PMNL)

Macrophages (MØ)

Acquired/Specific Immunity

Immunoglobulins

T-Lymphocytes

B-Lymphocytes

Conclusions of Clinical Importance

Further Reading

Chapter 4 Risk Assessment

Aim

Outcome

Risk Assessment

Risk Factors

Risk Markers

Risk Patients

Multi-Level Risk Assessment

Patient-level risk assessment

Mouth-level risk assessment

Tooth-level risk assessment

Site-level risk assessment

Patient-Level or Systemic Risk Factors

Genetic risk factors for periodontitis

Environmental risk factors for periodontitis

HIV disease

Behavioural risk factors for periodontitis

Poor oral hygiene as a risk factor

Smoking as a risk factor

Life-style risk factors for periodontitis

Stress as a risk factor for periodontitis

Malnutrition as a risk factor for periodontitis

Metabolic diseases/disorders as risk factors for periodontitis

Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for periodontitis

Practical points

Haematological risk factors for periodontis

Summary

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Natural History and Clinical Signs of Periodontal Diseases

Aim

Outcome

Natural History Studies

Linear Disease Progression Versus the Burst Theory

Disease Markers

Clinical Signs of Pristine Periodontal Health

Clinical Signs of Gingivitis

Clinical Signs of Periodontitis

Historical Verses Active Disease

Scenario 1

Scenario 2

Scenario 3

Concept of Site-Specificity

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Classification of Periodontal Diseases

Aim

Outcome

Why Do We Need Classification Systems?

Basic Terms that Appear in Such Systems

Acute

Chronic

Aggressive

Juvenile

Localised

Generalised

Historical Perspective pre-1999

International Workshop for Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions

Specific Issues with the 1999 System

Replacement of “adult” with “chronic”

Recurrent disease v. refractory

Aggressive periodontitis

Critique of the 1999 International Workshop System

A Practical Classification for General Dental Practice

The Ideal Classification System

Further Reading

Chapter 7 The Initial Consultation – Screening Examination

Aim

Outcome

The History

The History of the Complaint

The Medical History

The Social History

The Examination

The BPE

How?

The scoring/coding system

Recording the information

Management according to score

What are the Advantages and Disadvantages of the BPE?

Advantages of the BPE

Disadvantages of the BPE

Is the BPE a Good Thing?

Further Reading

Chapter 8 The Detailed Clinical Periodontal Examination

Aim

Outcome

The Clinical Periodontal Examination

Lack of Bleeding on Probing from the Base of the Pocket

Why?

How?

Recording the Information

Probing Pocket Depth (PPD)

Why?

How?

Recording the information

LOA

Why?

How?

Significance?

Recording the information

Furcation Involvement

Significance?

Detection?

Grading the severity of furcation involvement

Reporting furcation involvement

Differential diagnosis

Vitality testing

Tooth Mobility

How?

Grading of tooth mobility

Causes of tooth mobility

Recording the information

Recording a “Double Periodontal Chart”

Why?

How?

Advantages

Disadvantages

Errors Associated with Manual Probing

Choice of probe

What about Plaque Scores?

Further Reading

Chapter 9 Radiographic Examination and Special Tests

Aim

Outcome

The Radiographic Examination

Choice of Techniques

Dental panoramic tomograms (DPT)

Bitewings

Periapicals

Which Films to Take

Advantages of Radiographs

The Radiological Report

Disadvantages of Radiographs

With So Many Disadvantages Are Radiographs a Good Thing?

Special Tests

Referral of Patients

Important Changes in Radiology

Further Reading

Chapter 10 Periodontal Diagnosis and Prognosis

Aim

Outcome

Diagnosis

Possible Periodontal Diagnoses

Prognosis

General Prognostic Factors

Local Prognostic Factors

Further Reading

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 1

Periodontology – 1

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Chapple, Iain L. (Iain Leslie)

Understanding periodontal diseases: assessment and diagnostic procedures in practice. - (The quintessentials of dental practice)

1. Periodontal disease - Diagnosis 2. Periodontal disease - Treatment

I. Title II. Gilbert, Angela D. III. Wilson, Nairn H. F. 617.6′32

1-85097-308-3

Copyright © 2002 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 1-85097-308-3

This text is dedicated to my daughter,

Jessica Louise Chapple, born 7 September 2001.

Iain L C Chapple

Knowledge and understanding of the periodontal tissues and diseases are fundamental to the provision of effective oral healthcare. This first volume in the Quintessentials for General Dental Practitioners Series presents this knowledge and understanding in a succinct, authoritative, easy-to-read engaging style.

Each chapter includes aims, anticipated outcomes, high-quality illustrations to complement the text and carefully selected suggestions for further reading – features which will characterise the attractive range of books to follow in the Quintessentials Series. As a rich mine of information and guidance essential to good-quality periodontology in everyday clinical practice, Understanding Periodontal Diseases has a good deal to offer both established practitioners of all ages and student members of the dental team.

With a growing awareness of the benefits of oral health, patients living longer and retaining an increasing number of teeth throughout life, periodontology as presented in Understanding Periodontal Diseases is an essential element of successful clinical practice. For all those striving to improve the provision of oral healthcare for their patients, this book, in common with the volumes to follow in the Quintessentials Series, provides a most valuable asset – the means for all practitioners to apply the latest knowledge and understanding for the benefit of patients and the further development of the art and science of dentistry. I commend Understanding Periodontal Diseases to you as an outstanding first volume in the Quintessentials for Dental Practitioners Series.

Nairn H F Wilson

Editor-in-Chief

This text is the first of five books which aim to provide the general dental practitioner with an illustrated practical and contemporary guide to the management of patients with gingival and periodontal diseases. The first book in the series is entitled Understanding Periodontal Diseases: Assessment and Diagnostic Procedures in Practice and takes the reader on a logical journey through the assessment and diagnostic processes to enable practitioners to avoid diagnostic pitfalls and to identify risk patients for periodontitis. It provides summary background revision of anatomical issues and those relating to the disease process, clinical signs of health and disease and current concepts of disease classification. The reader is then led through a clinical diagnostic algorithm, including radiological and other special investigations and is provided with a look into the future for periodontal diagnosis.

It is hoped that having read this book the reader will be able to:

Understand current concepts of the periodontal disease process, its classification and clinical course.

Understand the concept of risk assessment and what risk factors are, and be able to assign a level of risk for their patients losing teeth due to periodontitis.

Identify healthy and diseased periodontal tissues, in their broadest sense, and understand how such features fit into current classification systems.

Diagnose the most common gingival and periodontal diseases/lesions.

Follow a simple periodontal diagnostic algorithm, including radiological and other special investigations, thereby ensuring that disease does not go undetected.

Decide on the most appropriate radiographs to take and to prepare and document a concise report of the key findings from such investigations.

Understand which special tests are required for certain conditions and what the results mean.

Broadly categorise lesions affecting the periodontal tissues and form differential diagnoses for such conditions.

Picture where periodontal diagnosis may be heading over the next ten years and therefore prepare their practice for potential change.

Iain L C Chapple

Angela D Gilbert

The authors would like to acknowledge with sincere thanks the following people. Dr John Strange and Dr Barbara Shearer for proof-reading the entire manuscript; Dr John Matthews for proof-reading Chapters 2 and 3; Mr Michael Sharland and Miss Marina Tipton for their photographic expertise; Dr Rachel Sammons for Figs 2-2, 2-3, 2-4, 2-5, 3-7; Mr H Donald Glenwright for the use of Fig 4-9; Dr John Rippin for the use of Figs 1-1, 1-4, 1-5; Dr Serge Dibart for the use of Figs 1-7 and 5-8; Dr Elizabeth Connor and her staff for radiological expertise and material; Mr Paul Hughes for his help with illustrations and Mosby Year Book Europe Limited for allowing us to reprint Figs 6-2 and 6-4.

Professor Chapple would like to acknowledge the help and support of his wife, Liz, throughout this venture. Dr Gilbert would like to thank Nigel, and her sisters Isobell and Joan for their unstinting support.

This chapter aims to provide the practitioner with a contemporary review of the important anatomical and micro-anatomical features of the periodontium.

At the end of this chapter the practitioner should be able to identify key clinical features that need to be assessed during the examination of patients’ periodontal tissues, since these features help inform diagnostic and treatment-planning processes.

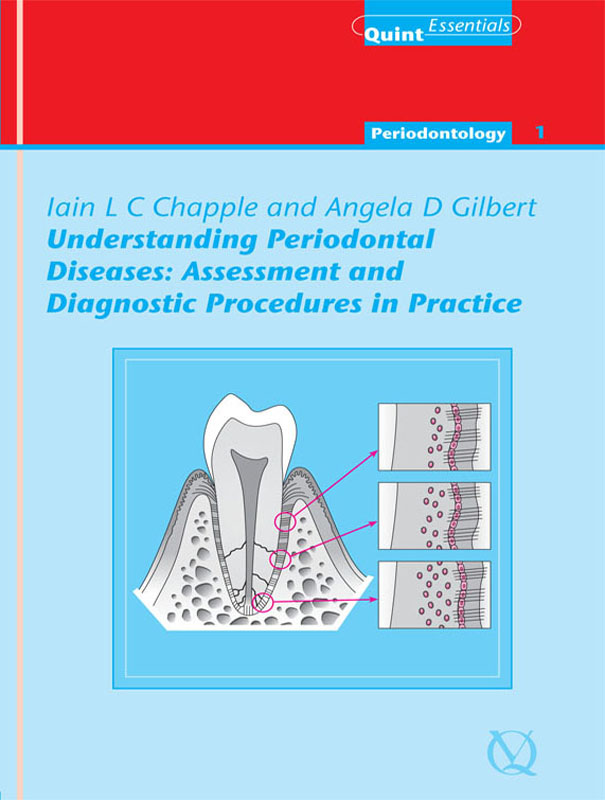

The periodontal tissues form the supporting apparatus of the teeth. Their role is to protect the teeth from masticatory forces and infection, thereby facilitating normal oral function and preventing premature tooth loss. As modern medicine and standards of health have prolonged human life expectancy the periodontal tissues have to perform these functions over considerably more years than they were designed for, and therefore recession, sensitivity and tooth mobility are daily management problems for the dental practitioner and patient. Additionally, the nature and extent of systemic problems that are created by a compromised periodontal attachment (e.g. the established link between periodontal disease and cardio-/cerebro-vascular disease) and the chronic microbial stimulus associated with retaining teeth for longer, is only just being realised. The healthy periodontal tissues are identified in Fig 1-1 and comprise:

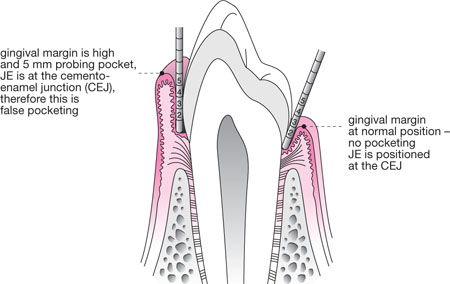

Fig 1-1 Schematic longitudinal section of a premolar and associated periodontal tissues. Applied anatomy is demonstrated alongside histology (photomicrographs) of key areas.

investing gingival complex (gingivae)

alveolar bone

periodontal ligament

root cementum.

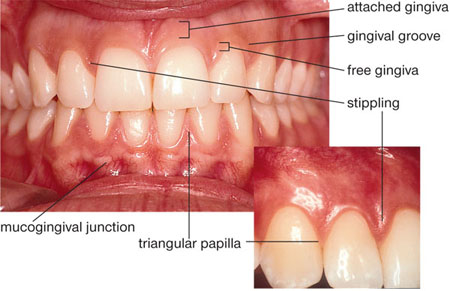

The gingivae comprise:

a gingival margin – the visible edge of the gingiva

a gingival sulcus – (or crevice) which in health is between 0.5 and 3mm in depth

the free gingiva – a mobile cuff of gingiva lying above the alveolar crest

the attached gingiva – a band of 1–9mm in length, which is bound down to the underlying alveolus and cementum, by collagen fibres of the dentogingival complex.

The line at which the free gingiva becomes attached gingiva is usually visible, under conditions of pristine gingival health, as the gingival groove (Figs 1-1 and 1-2). However, since the majority of healthy mouths have detectable levels of marginal and interproximal plaque present, they also have a degree of inflammation present histologically, hence clinical health and pristine health are now recognised as different conditions. In clinical gingival health, it is accepted that there may be very mild inflammation present and the gingival groove is not therefore always discernible.

Fig 1-2 An anterior view of “pristine gingivae” demonstrating applied anatomical features from Fig 1-1.

The gingival tissues are orthokeratinised and therefore, in health, appear paler or pinker than the lining oral mucosa, which is non-keratinised. The gingiva joins the oral mucosa at the mucogingival junction (MGJ), which is not visible in the palate, since palatal mucosa is entirely keratinised. It used to be thought that when the gingival margin was formed by oral mucosa (e.g. due to recession) rather than keratinised gingiva, the marginal tissues were less robust and resistant to the trauma of toothbrushing. However, studies have shown that a gingival margin formed by non-keratinised oral mucosa is as capable of retaining stability as a margin formed by keratinised gingiva, provided plaque control is good.

The free gingival tissues are separated from the crown of the tooth in health by the gingival sulcus or crevice, which on clinical probing varies from 0.5 to 3mm, for recommended probing pressures (20–25g or 0.2–0.25N) (Fig 1-3). If a healthy crevice is probed too firmly, the probe penetrates the base and enters the connective tissues. The crevice is washed out in health by gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) which flows out at a rate of 0.2μl per hour contributing 1ml per day to saliva. GCF is a serum transudate in health and is formed by serum moving passively from the arteriolar capillaries of the gingiva (Fig 1-4), through the gingival connective tissues and into the gingival crevice (Fig 1-5). In health, GCF contains everything serum contains, except for red blood cells, and, in addition, viable neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leucocytes; PMNLs) can be collected from it. During inflammation, the transudate becomes more like an inflammatory exudate and local components of that inflammatory process enter the GCF, which increases in flow rate and volume.

Fig 1-3 Schematic longitudinal section of a premolar and associated periodontal tissues, demonstrating a healthy sulcus and false pocketing arising due to overgrowth of the gingiva.

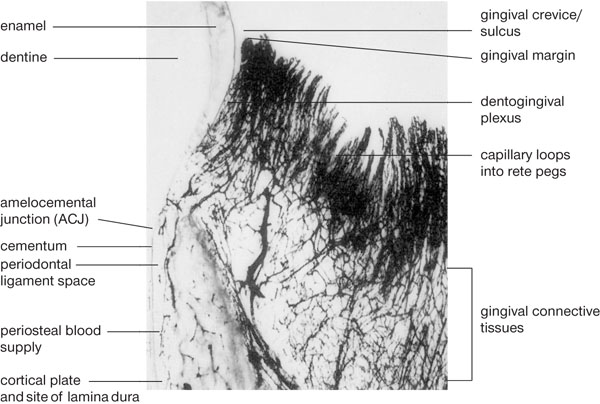

Fig 1-4 A black-and-white photomicrograph from the periodontium of a dog following injection of dye to demonstrate the rich gingival vasculature. Large vessels (arterioles) branch off a vast network of capillaries which form loops beneath the connective tissue rete ridges of the oral epithelium. The capillary network beneath the JE and SE is called the dentogingival plexus and serum from this plexus either returns to the post-capillary venules, or it enters the gingival crevice as GCF.

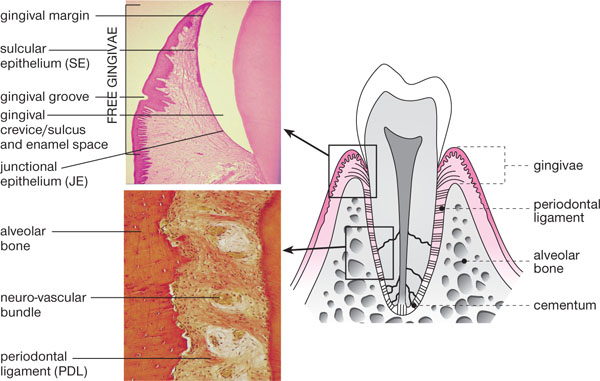

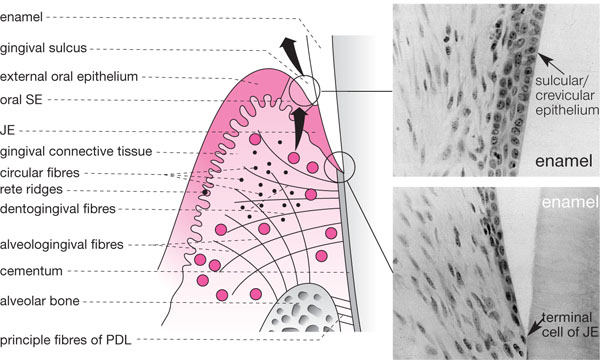

Fig 1-5 A schematic view of the gingivae demonstrating the gingival collagen fibre complexes. The SE and JE are also represented alongside in two photomicrographs demonstrating normal histology. Note how widely spaced the cells are and how they thin out forming a single “terminal cell” of the apex of the JE.

The gingival crevice is lined by highly specialised epithelia called sulcular epithelium (SE) and junctional epithelium (JE) (Fig 1-5). These normally adhere tightly to the crown, such that in pristine health no sulcus exists unless a probe is placed down from the gingival margin. The JE is unique as it forms an epithelial attachment (via hemi-desmosomes) to an internalised part of the skeleton (tooth with its investing alveolar bone). As enamel is derived from ectoderm embryologically (inner enamel epithelium) such a union is not unusual. However, once attachment loss has occurred (either recession or true pocket formation), the JE migrates onto cementum which is derived from mesenchyme. This results in a situation rather like a compound fracture of bone, where bone emerges from epithelium exposing the internal structures of the body to a hostile external environment. For this reason, the JE is permeable to GCF carrying the host’s defence cells (mainly PMNLs) and various other components of the inflammatory/ immune response, such as complement and antibody. The JE cells are widely spaced to facilitate this (Fig 1-5), but the downside of this arrangement is that bacterial products can also pass back into the gingival tissues and stimulate an inflammatory reaction. In health, this reaction is controlled and visible inflammation does not occur. However, as plaque accumulates subgingivally, the inflammation progresses within the gingival connective tissue underlying the JE and the latter eventually develops microscopic ulcers. When probed, blood can pass from the gingival connective tissues via the micro-ulcerations and can enter the crevice, creating the important clinical sign of bleeding on probing (BOP).

The gingival epithelium comprises:

oral epithelium

oral sulcular/crevicular epithelium

junctional epithelium.

The oral epithelium (Fig 1-6) is a stratified squamous epithelium with several layers, starting with the columnar basal cells. These germinal cells divide to produce cells that move up to the central zone (pentagonal/hexagonal cells within the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum), which ultimately flatten at the surface and lose their nuclei. The surface cells accumulate an impermeable protein called keratin and upon death they lie along the gingival surface forming a non-nucleated and impermeable keratinised layer (orthokeratinisation). There are over 20 different types of keratin and the keratin profile of epithelial cells characterises where they come from (e.g. gingival epithelium expresses cytokeratin – K1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 12, 16). The basal layer of cells follows a “rollercoaster” course as they travel over connective tissue ridges called “rete ridges” designed to increase the surface area of epithelial-connective tissue contact. The oral gingival epithelium forms a key part of the innate immune response by forming an impermeable physical barrier to bacteria and their products, which is bathed by saliva containing a variety of enzymes (e.g. lysozyme) and imunoglobulins (antibody). As the oral epithelium drops down inside the gingival margin, it becomes SE.

Fig 1-6 Photomicrograph of gingival epithelium from the facial surface demonstrating columnar basal cells (just in view) and pentagonal

cells of the stratum spinosum, with flattened surface cells which have accumulated keratin. Note the absence of nuclei at

the very surface, which is pure keratin and forms the permeability barrier to prevent microbial invasion.

(From Riviere, Lab Manual of Normal Oral Histology. Quintessence: Chicago, 2000)

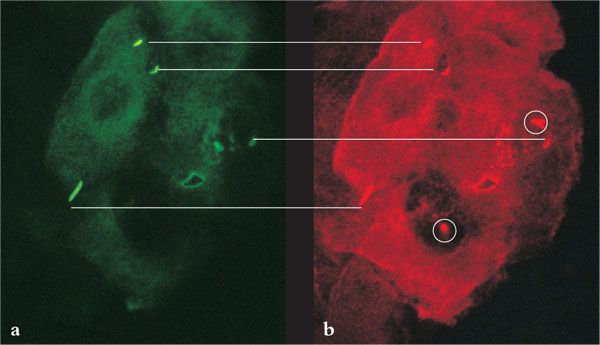

The SE is midway between the oral epithelium and the JE. There are no rete ridges for the basal cells to conform to (Fig 1-5). The basal layer divides rapidly, increasing turnover of the surface layer to help shed bacteria that attach to epithelial cells within the gingival sulcus. As a result these cells have less time to accumulate keratin and surface cells are para-keratinised (they still have nuclei), eventually losing their keratin surface as they touch the tooth. At this point they become highly specialised JE and express K19 and K13 in addition to the more ubiquitous keratins. Both the sulcular epithelial cells and junctional epithelial cells are “active epithelial cells”, capable of pinocytosis of bacteria (Fig 1-7) and production of important cell signalling molecules called cytokines (e.g. interleukin 1 – IL-1), which are chemical messengers that set up early inflammatory changes in the underlying gingival connective tissues.

Fig 1-7 (a) A single sulcular epithelial cell curetted from a patient who harboured the pathogen B.forsythus. Green fluorescein-labelled secondary antibody raised against B.forsythus. Under a microscope with a green filter, the green fluorescein dye labels B.forsythus located outside the cell.

(b) Red rhodamine-labelled secondary antibody raised against B.forsythus after holes were punched into epithelial cell membrane to allow antibody inside. The red dye stains B.forsythus located both inside and outside the cell. Thus, bacteria located outside the cell take up a double label and stain both red

and green. Those bacteria located inside the cell stain with the red label only. Note the bacteria inside the epithelial cell

appear inside vacuoles after pinocytosis.

The JE is a highly specialised epithelial tissue whose cells are non-keratinised and divide faster than any other normal epithelium (2-6-day turnover, compared to a month for oral epithelium). The JE is the key to determining when gingivitis becomes periodontitis. It is positioned onto enamel in health and, in longitudinal section, tapers from 20 to 30 cells thick to the apical cell of the JE (Fig 1-5), which is a single cell positioned at the CEJ. As the underlying periodontal attachment (ligament and cementum) becomes damaged during early periodontitis, the JE migrates down the root surface in an effort to wall off the vital internalised tissues from the potentially hostile bacteria within the crevice and their products. The apical migration of the JE is the first clinical indicator of periodontal attachment loss, and results in the formation of a true pocket. A false pocket arises when the gingival margin expands coronally (e.g. with drug-induced gingival overgrowth – Fig 1-3), the crevice deepens beyond 3mm, but the apical cell of the JE remains at the CEJ and there has been no attachment loss. A simple formula is used to define the clinical attachment level (CAL):

CAL = probing pocket depth + recession

where recession is the distance measured from the CEJ to the gingival margin. If the gingival margin is apical to the CEJ then this is recession; if it is coronal to the CEJ then this is “overgrowth” and false pocketing (Fig 1-3). Clearly, this assumes that the gingival margin is at the CEJ in health, when in fact it lies coronal to the CEJ and is broadly attached by hemidesmosomes up to 2–3mm above the CEJ (Fig 1-1). True recession should be measured from the CEJ to the point of epithelial attachment to the root surface (Fig 1-8), but this is not visible clinically and hence the term “clinical attachment level” rather than “histological attachment level” is used to overcome this. Clinicalclinicaltrue