Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Defining Success and Failure

Aim

Outcome

Terminology

Introduction

The Strindberg Concept

Methods of Evaluating Treatment Outcome

Clinical Evaluation

Radiological Evaluation

Histological Evaluation

Reasons for Reported Variations in Success Rates

Case Selection

Treatment Methods

Criteria for Evaluation

Observer Variation

European Society of Endodontology Guidelines

Definition of Success

Definition of Failure

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 2 Understanding Endodontic Failure

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Possible Causes of Failure

Persistent Infection

Intraradicular infection

Extraradicular infection

Cysts

Foreign Body Reaction

Fibrous Healing

Misdiagnosis

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 3 The Decision-Making Process

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Decision-Making

Case Selection

Case History

WHAT endodontic treatment has previously been provided?

WHY was the previous treatment required?

WHEN was treatment carried out?

By WHOM was the treatment carried out?

WHERE was the treatment carried out?

Clinical Examination

Extraoral examination

Intraoral examination

Radiographic Assessment

Restorative Considerations

Periodontal Health

Equipment

Experience

Patient’s Expectations and Cooperation

Cost

Risk of Complications and Probability of Biological Healing

Systemic

Local

Non-Surgical Versus Surgical Retreatment

How Do We Choose the Right Approach?

When to Treat?

Technical Deficiency

Procedural Errors

Pain, Swelling, Sinus Tract

Persistent Symptoms

New Coronal Restoration

When Not to Treat?

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 4 Biological Objectives of Retreatment

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

The Microbial Flora

Elimination of Microorganisms

Exclusion of New Microbial Infection

Fulfilling the Biological Objectives

Aseptic Treatment Regime

Access

Coronal access

Radicular access

Mechanical Instrumentation

Antimicrobial Therapy

Root canal irrigant

Chelating agents

Intracanal medicaments

Obturation

Coronal Temporisation and Restoration

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Disassembling the Coronal Restoration

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Coronal Restoration

Coronal Restoration Removal

Grasping forceps

“Sticky sweet” method

Levering instruments

Wedging devices

Tapping and pneumatic tools

Ultrasound

Occlusal Access

Removal of Posts

Uncover the Post

Remove the coronal restoration

Remove encasing restorative material and cement

Loosen and Extract the Post

Use of a bur

Ultrasound

Post removal devices

The Masserann kit

Meitrac Endo Safety System

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Achieving Radicular Access

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Removal of Gutta Percha

Single Cone or Poorly Condensed Gutta Percha

Hedstrom hand files

Rotary files

Ultrasound

Condensed Gutta Percha

Heat

Solvents

Gutta Percha Carrier Devices

Removal of Silver Points

Visible and Accessible

Loose

Possible to Gain Purchase

Sectional Silver Points

Removal of Paste and Cement

Soft

Hard

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 7 Managing Canal Obstructions

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

General Guidelines

Managing Retained Instruments

If Retrievable

Stage 1: Expose the coronal end

Stage 2: Loosen the instrument

Stage 3: Engage the instrument

If Not Retrievable

Managing Blockages and Ledges

Instrument Selection

Technique

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 8 A Surgical Alternative

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Apicectomy and Root-End Filling

Rationale

Medical and Dental Considerations

Preoperative Preparations

Surgical Kit

Anaesthesia

Flap Design and Reflection

Locating the Tooth Apex

Periapical Curettage

Root-end Resection

Root-end Cavity Preparation

Root-end Filling

Reinforced zinc oxide-eugenol cements

Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA)

Guided Tissue Regeneration

Flap Replacement and Suturing

Postoperative Care

Patient Review

Conclusions

Further Reading

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 23

Endodontics – 2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Chong, Bun San

Managing endodontic failure in practice. - (Quintessentials of dental practice; 23. Endodontics; 2)

1. Endodontics

I. Title II. Wilson, Nairn H. F. III. Whitworth, John M.

617.6´342

ISBN 1850973091

Copyright © 2004 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 1-85097-309-1

Despite new materials, innovative techniques and a plethora of novel devices, the continuing growth and trend towards more complex forms of endodontics has been accompanied by an increasing need to manage endodontic failures. Such failures pose many, varied challenges which, if successfully overcome, can be both professionally rewarding and a real practice builder.

Managing Endodontic Failures in Practice provides a concise, practical overview of the “when” and “how” to save teeth with an unsatisfactory and often deteriorating endodontic outcome. From diagnosis to the monitoring of successfully re-treated teeth, Managing Endodontic Failures in Practice is clearly the work of an endodontist “in the know” and “up to speed” on the latest thinking, developments and techniques.

The valuable experience and enjoyment of reading this book is enhanced by its easy-to-read style and the large number of high-quality illustrations included in the text – just as you would expect of a Quintessence publication. Altogether this excellent addition to the Quintessentials of Dental Practice Series is a most worthwhile and enlightening volume – ideal continuing professional development for the practitioner visited by patients who present with different forms of endodontic failure.

Nairn Wilson

Editor-in Chief

With a continuing improvement in oral health and a change in patient attitude, it is no longer acceptable to extract teeth simply because of periapical disease and endodontic failure. Advances in scientific knowledge and technical skills have helped improve the prognosis of treatment, but it may not always lead to the desired healing response in clinical practice. If initial treatment is unsuccessful, practitioners are increasingly expected to possess the necessary knowledge and skills to perform ever more technically demanding procedures to save teeth. The focus on evidence-based treatment has resulted in secondary care providers, such as local oral surgery units, no longer being willing unquestioningly to accept failing endodontic cases for surgery, prior to an attempt having been made to retreat by non-surgical means. The aim of this book is therefore to provide practitioners with an understanding of the biological principles and the practical techniques to handle endodontic failures. To this end, it is hoped that its contents are clear, rational, practical and helpful in dealing with endodontic retreatment situations in everyday clinical practice.

Since careful treatment planning is integral to success, a substantial part of this text is dedicated to case assessment and selection. It is inevitable that there will be some repetition of relevant points. There is a myriad of techniques available to manage the many and diverse retreatment situations. It is impossible to cover them all in this book. Emphasis is placed, however, on principles and techniques relevant to general practice, followed briefly by some insight into more advanced methods. For practical instruction on retreatment techniques, practitioners are encouraged to attend hands-on courses.

Bun San Chong

I would like to thank my family, Grace, James and Louisa for their understanding and support and for accepting my periodic absences whilst immersed in writing this book. “Muchas gracias” to Monica for all her help and nursing assistance over the years.

To review the methods of evaluating the outcome of endodontic treatment, explain the reasons for reported variations of success rate and describe the criteria for success and failure.

After studying this chapter, the practitioner should have an understanding of how the concepts of success and failure are defined, the process of evaluating treatment outcome, and the principles of justifying remedial treatment.

Endodontic treatment is used as a generic term to cover the whole spectrum of pulp and periapical therapy. Root canal treatment describes a specific procedure for treating the dental pulp when irreversible damage has occurred, or when vitality is compromised by disease or injury. Although there is a distinction between the terms, in this book, endodontic treatment and root canal treatment are used interchangeably, as in common usage.

It has been said that there is no such thing as failure, just different degrees of success. There is some truth in this statement and it highlights the difficulties of defining success and failure objectively. Therefore, before looking at how to manage endodontic failure, it is pertinent to consider how failure may be defined.

The traditional, standard notion of success and failure is based on the stringent criteria encapsulated by the so-called “Strindberg Concept”. According to Strindberg (1956) the only satisfactory postoperative outcome, after a predetermined postoperative period, is clinically a symptom-free tooth and radiologically the appearance of a normal periapex. Put simply, “success” is defined as the lack of visible signs of disease while “failure” is defined as the presence of any signs or symptoms indicating disease. Such a concept is very “black and white”, with a definite cut-off point.

The “Strindberg Concept” is based exclusively on our knowledge of the disease process and represents an “ideal” concept of disease. It can, however, be perceived as being too dogmatic and inflexible for use in everyday clinical practice.

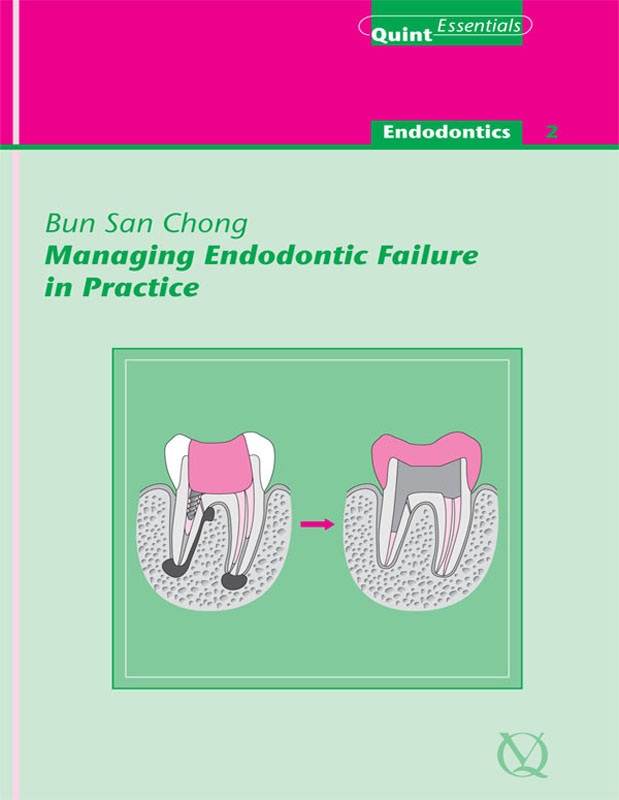

In theory, there are three methods (clinical, radiological and histological) available to evaluate the results of endodontic treatment (Fig 1-1).

Fig 1-1 Methods of evaluating treatment outcome.

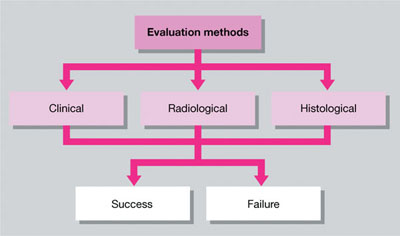

The patient is questioned about any symptoms experienced, whether the tooth feels normal and is comfortable in function. A clinical examination is then carried out to look for signs of disease such as the presence of:

a swelling

a sinus tract (Fig 1-2a) or

tenderness.

Fig 1-2 Signs of failure. (a) Clinical – a buccal sinus tract. (b) Radiological – a periapical radiolucent area.

An absence of abnormal clinical signs and symptoms is considered indicative of success. There is an element of subjectivity, however, when assessing treatment outcome clinically. Although there is little question if overt signs or symptoms of disease are present, a patient’s lack of symptoms may not necessarily mean that the tooth is disease-free and will remain symptom-free. Chronic lesions may have varying presentations, with the patient being unaware of their presence perhaps until, with little warning, alterations in the host/microbial balance transform the dormant lesion into an acute phase; this is something we have all witnessed often.

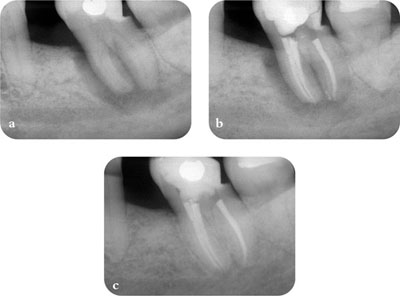

Radiographs of the tooth are taken and processed using a standardised technique to ensure a good quality, undistorted image. The radiographs are viewed on a light-box, with magnification and ideally with extraneous light blocked off (Fig 1-3). The following are evaluated:

quality of the root filling: in particular, its length and density

periodontal health, including the width of the apical and lateral periodontal ligament space

presence, location, size and nature of the margin of any radiolucencies (Fig 1-2b) or radiopacities.

Fig 1-3 Radiographs are viewed on a light-box using a film magnifying cone.

In essence, the task is to detect any features that are not consistent with the radiographic characteristics of healthy periapical tissues. If available, previous radiographs should be used for comparison to ascertain any differences in radiographic appearance with time (Fig 1-4).

Fig 1-4 Previous radiographs should be used for comparison when assessing treatment outcome. (a) Pre-op radiograph. (b) Post-op radiograph. (c) Two-year review radiograph.

A major problem with the radiological assessment of treatment outcome is that:

not all periapical lesions are detectable – detectability is dependent on the size of the lesion and its location. In addition, a positive radiological finding does not always correspond to the existence of a pathological lesion which needs intervention; for example, healing by scar formation may have occurred (see Chapter 2).

Other difficulties include:

the need for baseline information to understand follow-up observations and put them in context; there may be a substantial lesion, but it may be reduced in size compared to earlier images

the problem of inter and intraobserver differences; we are all biased in our judgements and decision-making

operator bias; if the assessor was responsible for the treatment, it may be difficult to be objective and decisions are likely to be especially loaded. Equally those seeking to intervene may be too condemning in their desire to get on and treat.

Studies have shown that there is relatively poor agreement amongst operators when interpreting radiographs. Although problems with radiological evaluation of treatment outcome cannot be completely eliminated, they can be reduced by:

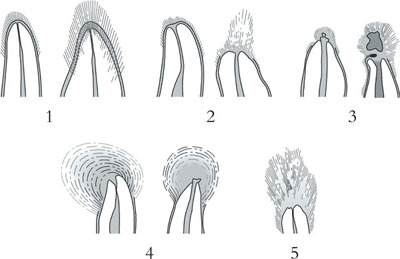

formal scoring systems, such as the Periapical Index (PAI), devised to aid radiological assessment of endodontic treatment outcome. In the PAI system (Fig 1-5) a set of five radiographic images denoting either a healthy periapex (score 1) or an increasing extent or severity of apical periodontitis (scores 2-5) is used as a reference when scoring cases

formal observer calibration; objective observations may be improved with special training

statistical methods, such as Kappa statistics, an index which compares the agreement against that which might be expected by chance.

Fig 1-5 The Periapical Index (PAI), a set of five reference visual images denoting either a healthy periapex (score 1) or an increasing extent or severity of apical periodontitis (scores 2-5). (Courtesy of D. Ørstavik.)

Whilst suited to standardised epidemiological surveys, these methods are of limited value in everyday general practice, where an element of judgement and pragmatism based on full understanding of circumstances must prevail. This is not an excuse, however, for uncritical appraisal of failing cases. The monitoring for radiological as well as clinical signs of healing is still important in assessing treatment outcome.

In order to carry out a histological evaluation, surgery is necessary to obtain a block section of the periapex. The block section is processed for histology and examined microscopically. The aim is to determine, at the cellular level, whether there is any evidence of inflammation or other signs of disease at the periapex. The two main problems with the histological assessment of treatment outcome are:

the need to obtain block sections

the possibility of artefacts introduced during tissue processing; delicate histological sections may be distorted or damaged.

Purists may consider this method of evaluation the “gold standard”, but it is again not a method that is applicable in everyday clinical practice. To biopsy all cases to evaluate healing is clearly unethical and unnecessary, let alone unacceptable to patients.

There are countless reports on the outcome of endodontic treatment and, not surprisingly, differences in reported “success” rates. Whilst it is not the intention of this chapter to review all of them, it is important to say a few words about possible reasons for the apparent lack of consensus.

Studies vary in the teeth included and the degree of technical difficulty in their treatment:

anterior or posterior teeth

single or multi-rooted teeth

a mixture.

There are also:

varying numbers of subjects

subjects of different age

differences in preoperative pulpal and periapical status at the start of treatment.

Studies vary greatly in:

techniques employed for canal preparation, medication and obturation

materials used

operator philosophy (e.g. single or multi-visit) and skill.

These variables may be related to operator preference and common approaches contemporaneous at the time of the study. The techniques and materials originally employed may not be relevant to current practice. Operator skill, or the condition under which treatment is delivered cannot be underestimated, epidemiological studies having revealed discrepancies between success rates of endodontic treatment performed in specialist clinics compared with general practice.

The difficulties of objective evaluation have already been considered. In research studies, observers should be trained and calibrated, but variations in study methods still remain. These include:

parameters recorded

criteria for success and failure

methods of assessment

retention of subjects for follow-up in a long-term trial

observation period

analysis of results.