Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 Introduction

What Makes this Book Different?

Section 1: Communication

Section 2: Patients

Section 3: Dental Health Education in Practice

Chapter 2 Basic Communication Skills

Aim

Outcome

The Importance of Clinical Communication Skills

Questioning

Open Questions

Focused Questions

Closed Questions

General Guidelines for Questioning

Explaining

Listening

Level/Position

Proximity

Posture

Eye Contact

Non-Verbal Reinforcers of Speech

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 3 Advanced Communication Skills

Aim

Outcome

Obtaining Consent

Breaking Bad News: General Principles

General Principles for Handling Complaints and Solving Problems

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 4 Communicating in Special Dental Situations

Aim

Outcome

Defining Special Needs

Are Patients with Special Dental Needs Treated in General Practice?

Communicating with Older People

Hearing impairment

Visual impairment

Communicating with People with Learning Disabilities

Communicating with People with Mental Illness

Communicating with People from Ethnic Minorities

Communicating with the Homeless Patient

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Understanding and Finding Solutions: The Dentally Anxious Patient

Aim

Outcome

Dental Anxiety: A Perpetual Problem?

Assessment of Dental Anxiety

Behavioural Management and Dental Anxiety

Tell-Show-Do

Hypnosis

Biofeedback

Relaxation

Long-Term Follow-up and Continuing Care

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Understanding and Finding Solutions: The ‘Difficult’ and Dissatisfied Patient

Aim

Outcome

Defining Difficult Patients

Vignette 1: A Case of Phantom Toothache

Vignette 2: A Case of Dysmorphophobia

Vignette 3: A Man with a Dry and Painful Mouth

The Dentist-Patient Relationship and the Treatment Alliance

Are There any Solutions?

Self-Assessment

Assessing the New Patient

Treat or Refer

In summary

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 7 Preventive Health Principles for Dental Practice

Aim

Outcome

Definitions of Health Education

How can Practice-Based Oral Health Promotion be Achieved?

Assessment of Need

Assessment of Preventive Oral Health Need

Strategies for Primary Prevention: Health Behaviour Models and Health Gains

Strategies for Secondary and Tertiary Prevention: Health Behaviour Models and Health Gains

Stages of Change Model

Application for Dental Practice

Motivational Interviewing

The ‘Not Ready to Change’ Patient

The ‘Ambivalent or Unsure’ Patient

The ‘Ready to Change’ Patient

Models for Negotiating Health Goals: The ‘ARMPITS’ Strategy

Guidelines to Best Practice when Negotiating Behaviour Change

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 8 Integrating Oral Health Education into Primary Dental Care

Aim

Outcomes

Dental Health Education in Everyday Clinical Practice

The Scientific Basis of Oral Health Education

Fluoride:

Dietary control:

Plaque control:

Erosion:

Advice for denture wearers:

Oral cancer:

Preventing Dental Diseases in Primary Dental Care

Preventing Dental Caries

Preventing Periodontal Disease

Promoting Dental Attendance

Oral Cancer, Opportunistic Screening and Smoking Cessation

Oral Cancer: Opportunistic Screening

Oral Cancer: Dealing with a Positive Diagnosis

Oral Cancer: Intervention for Smoking Cessation

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 9 Communication, Stress and Improved Patient Care

Aim

Outcome

Sources of Occupational Dental Stress

Workload

Time-Scheduling

Job-Related Stressors

Patient-Related Stressors

Staff/Technical-Related Stressors

Stress and Personality

Responses to Stress

What is Burnout?

Coping with Occupational Stress and Burnout

Recognition of Danger Signs: Alcohol and Drug Abuse

Considering Change, Implementation and Coping

Planning for Retirement

Conclusions

Further Reading

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 30

Operative Dentistry – 4

British Library Cataloguing-in Publication Data

Freeman, Ruth, Dr

Communicating in dental practice: stress-free dentistry and improved patient care. - (Quintessentials of dental practice; 30)

1. Communication in dentistry 2. Dental personnel and patient

I. Title II. Humphris, Gerry III. Wilson, Nairn H. F. IV. Brunton, Paul A.

617.6

ISBN 1850973148

Illustrators: Laura Andrew & Abi Le Santo

Copyright © 2005 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 1-85097-314-8

Effective communicating is fundamental to success in clinical practice. Indeed, many tensions between patients and members of the dental team, in particular complaints, stem from failures in communications.

There is a great deal more to communicating in healthcare provision than simply applying interpersonal skills and techniques developed in everyday life. This important volume in the multifaceted Quintessentials series provides great insight into key communication skills and techniques of special relevance to the dental team. Following consideration of basic and advanced communication skills, with reference to special dental situations, the authors – international leaders in the field – focus in on major communication challenges in clinical practice, such as communicating effectively with anxious, “difficult” and dissatisfied patients, communicating and integrating preventive and oral health messages and education in primary dental care, and ways in which patient care can be improved without adding to the stress of frontline clinical practice.

This excellent addition to the unique Quintessential series is both a springboard and stimulus to communicating more effectively – a means to less stress, fewer complaints, improved clinical outcomes and patients who better understand their problems and appreciate their oral healthcare. It is not always what you do, but how you communicate it! The evening or two it will take to read this carefully crafted book will be time well spent.

Nairn Wilson

Editor-in-Chief

We would like to thank Catherine Coyle for providing the example of communicating with a boy with Asperger’s syndrome.

Dentistry can be a rewarding and satisfying profession. Dental health professionals must have a variety of skills to hand. These include not only clinical and technical skills but also those associated with patient management, managerial and financial acumen. This is reflected in their financial remuneration, which is often above average for staff employed within health-related disciplines. The principals of practices and, to a lesser extent, associates, have the ability to work at a pace they can ultimately decide upon. In reality this may seem something of a fantasy, as the demands on the modern practitioner appear less amenable to individual control. However, on closer inspection there are demands other than the financial and management constraints of running a busy practice that can cause difficulties. Some of these problems relate to patient and staff interaction and include the following:

difficult and demanding patients

encouraging patients to adhere to oral health recommendations

managing pain

the dentally anxious patient

patients with unexplained symptoms

informing patients about oral health, self-care and specialist treatments.

The aim of this book is to signpost principles and actions that will enhance the process of communication with patients and mitigate many of the difficulties listed above. The book will provide a framework within a dental context to assist with understanding the complex set of factors that make up dental practice in the 21st century. The authors have distilled the current literature into an authoritative account, with a small number of key references listed at the end of each chapter, including selected further reading.

This volume translates recognised psychological and sociological principles into everyday clinical practice. The emphasis will be on application to the day-to-day working of the dental health professional. Hence, a major theme throughout the book will be communication between the dentist and the patient. Enhancement of an appropriate working relationship is a central focus. Less space will be devoted to systems of care outside the practice (for example, health organisations, mass media interventions and oral health surveys).

Self-care is a neglected subject in the health professions. The professional and philosophical underpinnings of primary dental care have tended to diminish the need to maintain good physical and psychological health of its practitioners while concentrating efforts on improving patient care. The authors would prefer to redress the balance and advocate the need of practitioners to ensure that they care for themselves enough to:

maintain high standards of care for patients

develop new techniques of prevention and treatment as they come on stream

achieve longer-term personal goals and therefore become more resilient to the vagaries of occupational stress and burnout

be able to recognise physical and emotional problems associated with work and outside the workplace.

Occupational stress is an easily recognised phenomenon in modern dental practice. However, the term has a tendency to be overused, or simply raised without further discussion of some of the underlying reasons for its experience for many working in dental practice. Alternatively, causative agents that can be championed conveniently (such as the remuneration system) exclude the individual practitioners and the means at their disposal to at least attempt to minimise some of these pressures. The reader is invited to accept the possibility that many of the day-to-day hassles that feature in practitioners’ work can be analysed and interpreted from the interaction that occurs between patient and practitioner.

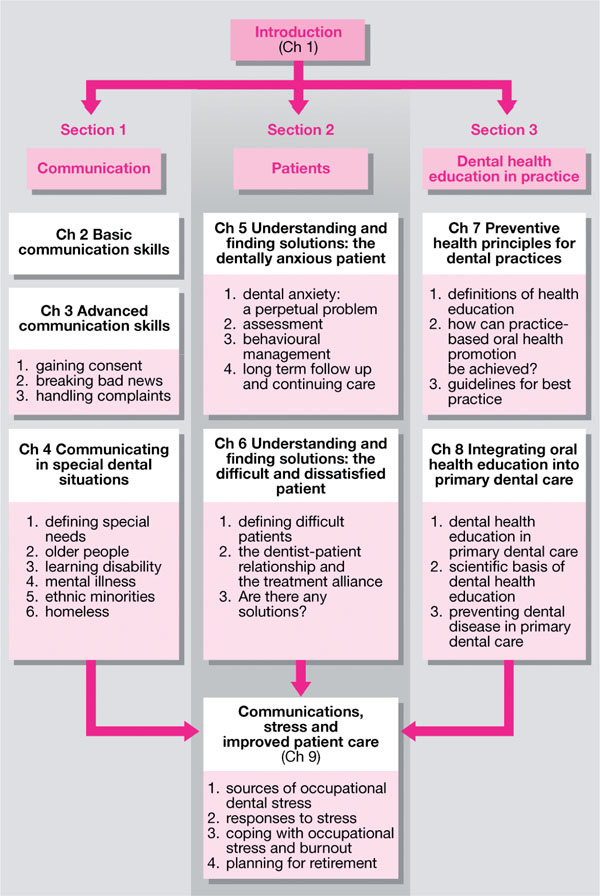

This section comprises three chapters (Chapters 2-4). Chapter 2 deals with different aspects of communication. Practitioners may be familiar with many of the fundamental building blocks of communication skills utilised in dentist-patient interactions. These basic skills are cornerstones that lend themselves to repeated attention and practice in the workplace. Even the simple application of a well-placed or considered greeting can pay dividends to the overall satisfaction and outcome from the patient’s perspective. Hence, these skills are described and illustrated from the dental practice perspective.

Chapter 3 expands the communication theme by identifying important areas of clinical practice that command excellent use of advanced communication skills. Negotiating with patients various options available for treatment entails a complex blend of skills to ensure cooperation and adherence to the eventual agreed plan.

Obtaining consent for treatment requires sensitive handling to ensure that patients are fully conversant with the implications of their decision to embark on a treatment, including possibilities of success or failure and any side-effects. Included in these discussions, in all probability, will be estimates of costs of care and requests for payment (under fee for item, insurance payment or private contract schemes). An additional area of communication often confronted by clinicians is the breaking of bad news to patients. This may take the form of simply announcing to a patient that a tooth requires extraction. The meaning associated with the tooth loss can be assessed with a well-chosen open-ended question. Alternatively, providing unwelcome news to patients may take the form of a potentially frightening opinion, such as a suspicious lesion under the tongue, indicative of an oral squamous cell carcinoma. Admittedly, this is a very infrequent circumstance, but one that dentists have stated as being one of the most stressful incidents in their working lives. It is assumed that practitioners who think about these scenarios and hopefully practise their skills in continuing professional development training events will improve their competency and also confidence.

Patient expectations are known to be increasing in the health care field. Without clear explanations of procedures and realistic estimates of outcome and costs the clinician will be prone to complaint. Even the most diligent and competent clinician will be exposed to the risk of treatment unexpectedly failing. Human error is, unfortunately, a feature of health service provision and requires sensitive handling and management. Over 90% of litigation in the health service has been attributed to poor communication skills. Some key points can be offered to the practitioner to prevent a complaint escalating into formal action (considered by the majority of dentists to be the most extreme stressor).

Chapter 4, the last of this first section of the book, extends the discussion of communication skills applied in certain situations to focusing on particular groups of patients. It is acknowledged that the identification of a patient group by attaching a label has negative connotations. For example, the ‘elderly’, a term sometimes applied to those over the age of 60, can introduce punitive stereotyping and discrimination. To make some generalisations for a particular group can, however, be illuminating if the practitioner is aware that the group profile will vary according to the individual presentation of the patient and that the requirements of the individual should remain paramount. The communication skills associated with the following groups will be described: older people, people with physical and learning difficulties.

The second section, consisting of two chapters, focuses on the patient. A whole chapter (Chapter 5) is devoted to the anxious patient, who has been acknowledged as one of the most frequent and demanding types of patient the practitioner will meet. Much has been written about the assessment and management of the dentally anxious patient. The approach adopted in this chapter will summarise the recognised methods of identifying the anxious and phobic patient and suggested ways of encouraging successful treatment and continued access to the dental practice for long-term oral health care.

The second chapter (Chapter 6) of this patient section introduces the management of patients with difficulties that are not necessarily dental in origin but are expressed as oral symptoms or problems. Without a considered assessment and understanding of the complexities of the presenting symptoms and complaints, the practitioner may be drawn into unnecessary treatment or referral for further investigations. Attention to detailed history taking and formation of the treatment alliance (working relationship) are important features in providing appropriate care from the dental practice setting.

The last section, consisting of two chapters, presents key material for practitioners to conduct, essentially, one-to-one dental health education with their patients. This work rests on the ability of the practitioner to communicate effectively (a central theme of this book) and to be aware of the substantial advances and benefits to patients available from adoption of these approaches. Chapter 7 presents a number of the extant models that have influenced dental health education over the years. They have been drawn from various areas and have had proven value in improving patient knowledge, beliefs and behaviour in relation to dental health behaviours such as toothbrushing, diet control and dental attendance.

Chapter 8 continues with a series of examples where these models have been applied in one form or another. The evidence base for many of these preventive interventions is commented upon. Benefits can be demonstrated with one-to-one approaches in dental health education. All members of a practice should work to the same preventive protocol to have a synergistic effect. Furthermore, developing a preventive philosophy for the practice will provide additional outcomes for the general dental practitioner (for example, reduced stress) and the patient (for example, quality of life).

Chapter 9 concludes the book by returning to the major theme of improving patient care through the maintenance of self-care and practice of excellent communication skills. In reality, problems occur both personally and in the workplace. Practitioners are given ways of assessing themselves to indicate whether a problem may exist (for example, burnout or excessive drinking). It is the expected outcome of this book for the reader to appreciate and adopt communication skills and self-care actions to improve service delivery to patients visiting the dental practice based in primary care.

To present the fundamental building blocks and processes of communication between dental personnel and patients.

After reading this chapter the reader will understand the components of communication skills and have guidance on when to use each skill appropriately.