in

Management of

Advanced Periodontitis

Assistant Professor

Department of Periodontics

School of Dental Surgery

René Descartes University-Paris 5

Paris, France

English Translation by

Private Practice

Paris, France

|

Paris, Berlin, Chicago, Tokyo, London, Milan, Barcelona, Istanbul, Moscow, New Delhi, Prague, São Paulo and, Warsaw |

First published in French in 2002 by Quintessence International, Paris

Le Traitement des Parodontites Sévères

To Monique

© 2005 Quintessence International

Quintessence International

11 bis, Rue d’Aguesseau

75008 Paris

France

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Design: STDI, Lassay-les-Châteaux, France

Printing and Binding: EMD, Lassay-les-Châteaux, France

Printed in France

I would like to acknowledge the colleagues listed below:

Salima Benmehdi

Claire Boski

Alain Canac

Fabrice Chérel

Michel Degrange

Cédric Fiévet

Bernard Fleiter

Dominique Guez

Alain Lautrou

Thierry Perronnet

Philippe Rajzbaum

Franck Renouard

Thierry Taïeb

Jean-François Tulasne

For their valuable help and dedication, I would also like to thank Jean-Louis Giovannoli and Jean-Marie Korbendau

| Cover | |

| Table of Contents | |

| 1 | Severity of Periodontal Disease |

| Severity Criteria | |

| Prevalence of Periodontal Disease | |

| 2 | Pathogenesis of Periodontal Disease |

| Biofilms and Bacterial Complexes | |

| Red complex | |

| Orange complex | |

| Yellow complex and green complex | |

| Conditions for the Development of Periodontal Disease | |

| Periodontal Infection | |

| Host-Bacteria Interactions and Pathogenesis of Periodontal Disease | |

| Histologic Alterations and Tissue Destruction | |

| Periodontitis and Systemic Disease | |

| 3 | Diagnosis of Advanced Periodontitis |

| Classification | |

| Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Periodontal Disease | |

| Healthy periodontium | |

| Pathologic periodontium | |

| Treated periodontium | |

| Periodontium undergoing periodontal maintenance | |

| Microbiologic Diagnosis | |

| Indications for microbial analyses | |

| Microbiology of healthy and pathologic periodontal tissue | |

| Complexity Factors | |

| 4 | Infection Control in Periodontics |

| Criteria for Therapeutic Success | |

| Effects of Bacterial Plaque Control | |

| Effects of Scaling and Root Planing | |

| Cementum elimination | |

| Calculus elimination and attachment gain | |

| Bleeding indices | |

| Bacterial flora | |

| Effects of Antibiotic Therapy | |

| Effect of antibiotic therapy combined with scaling and root planing | |

| Treatment planning for infection control | |

| Effects of Surgical Therapy on Bacterial Flora | |

| Effect of scaling and root planing | |

| Long-term outcome of surgical treatment compared with nonsurgical treatment | |

| Which surgical treatment should be selected? | |

| Effects of Antiseptic Medications | |

| Plaque-Induced Gingivitis | |

| 5 | Treatment of Advanced Periodontitis |

| Chronic Periodontitis | |

| Marginal chronic periodontitis | |

| Moderate to locally advanced chronic periodontitis | |

| Case report of moderate chronic periodontitis with locally advanced sites | |

| Generalized advanced chronic periodontitis | |

| Aggressive Periodontitis | |

| Moderate aggressive periodontitis | |

| 6 | Adjunctive Therapy |

| Aggressive Periodontitis and Occlusal Trauma | |

| Aggressive Periodontitis and Loss of Posterior Occlusal Support | |

| Advanced Chronic Periodontitis with Multiple Associated Disorders | |

| Advanced Chronic Periodontitis and Orthodontics | |

| High-Risk Sites | |

| Deep pockets and bone defects | |

| Guided tissue regeneration for treatment of an osseous lesion | |

| Treatment of an osseous lesion with bone grafting and regeneration | |

| Interradicular lesions and conservative treatment | |

| Interradicular lesions and implants | |

| Mobile teeth and splinting | |

| Mobile teeth and implants | |

| High-Risk Patients | |

| Genetic predisposition factors | |

| Smoking and periodontitis | |

| Diabetes | |

| Stress | |

| 7 | Prognosis and Long-term Outcome |

| Limits to Conservative Treatment | |

| Advanced, Locally Terminal Periodontitis | |

| Implants and Risk of Infection | |

| Peri-implant flora | |

| Consequences of plaque accumulation around implants | |

| Periodontal infection and peri-implantitis | |

| Terminal periodontitis and implants | |

| Periodontal Maintenance | |

| Methods | |

| Therapeutic goals | |

| Treatment considerations | |

| Individual maintenance therapy | |

| Special Circumstances | |

| Frequency of professional follow-up | |

| The Interproximal Space | |

| Long-term Outcome of Advanced Periodontitis | |

| Glossary | |

| Bibliography | |

| Severity of Periodontal Disease |

|

Severity Criteria

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory disease caused by a bacterial infection. It is characterized by a progressive destruction of the dental attachment tissues. Left untreated, it may lead to complete loss of dental attachment structures and subsequently loss of teeth.

The primary objective of treatment is to arrest the progressive destruction of periodontal tissue and thus to arrest loss of attachment structures. However, the infectious process involved in periodontal disease is complex. Host susceptibility and the presence of pathogenic bacterial species, whether exogenous or commensal, interact and either promote or hinder the progression of the disease. Simultaneously, numerous local or environmental factors exert an influence on the etiologic agents and the course of disease. Because of its multifactorial nature, periodontal disease is difficult to manage. In formulating treatment strategies, both the patient’s periodontal susceptibility and the amount of periodontal destruction need to be taken into account. Repair and regeneration have become realistic objectives in the current context of periodontal therapeutics. For this reason, a methodic assessment of severity factors is a crucial step in treatment planning.

Severe periodontal disease is characterized by:

• Destruction of periodontal attachment tissue exceeding one third of the root’s length

• Class II or III furcation invasion

• Probing depths exceeding 6 mm

• Attachment loss exceeding 4 mm

Some teeth have already been lost or are unlikely to be maintained. The indication of prosthetic restorations for the replacement of missing teeth denotes the irreversible aspect of treatment in the periodontal patient. However, prosthetic rehabilitation may seem a risky endeavor in the context of uncontrolled periodontal disease. This raises several questions concerning both the disease itself and the global treatment strategy:

• Is infection control possible in all forms of periodontitis?

• Are there severity factors? How can they be detected? Can they be eliminated?

• What are the risk factors?

• What would be the best treatment strategy?

• To what extent can a conservative approach be applied?

• What are the different criteria that indicate the decision to extract?

• When should the decision to extract be made?

• What is the prognosis for the remaining teeth?

• Is it possible to place implants in the context of advanced periodontal disease?

• Should we carry out periodontal treatments less often and place implants more often?

• What are the optimal conditions for successful therapy?

In the 1990s, the strategy consisting of root debridement with scaling and planing with or without surgical techniques and followed by periodontal maintenance every 3 to 6 months was considered the best treatment for the majority of periodontal diseases (Goodson 1994). However, the so-called refractory forms emerged; these were characterized by poor response to treatment (Figs 1-1a and 1-1b). In these specific cases, antibiotic therapy was recommended. Since then, however, progress in microbiologic knowledge no longer limits the use of antibiotic therapy to the refractory forms of periodontal disease. Taken together, these elements demonstrate the need for a sound understanding of the complex microbiology of periodontal disease in clinical practice.

A better understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of periodontal diseases has allowed for the development of new guidelines for management and treatment; this represents a major step toward carrying out treatment strategies better suited to individual patients. An increasingly specific approach, taking into account factors such as patient susceptibility, features of periodontal infection, and individual severity factors, will no doubt lead to a reduction of the number of refractory forms and lay out a clinical context favorable to tissue response.

The American Academy of Periodontology’s 2000 classification now serves as a reference. Periodontal disease treatments should be carried out in accordance with the diagnostic criteria specified in this classification. Advanced periodontitis is most often observed in younger patients, though it does not represent a distinct clinical subset; it is observed in chronic and aggressive forms of periodontal disease, both of which represent the principal subunits of the new classification. In the case of chronic periodontitis, treatment is relatively straightforward: the infection is characterized by a significant amount of plaque buildup and features a predominant commensal bacterial population with local aggravating factors. In the case of aggressive periodontitis, a more specific protocol must take into account the involvement of a more complex bacterial flora, specific patient susceptibility factors, and additional risk factors. Here again, formulating a precise diagnosis is a crucial step in patient management.

Defining treatment success in periodontal practice represents a difficult task. It implies both complete elimination of infectious processes and associated inflammation as well as durable prevention of recurrence in all previously pathologic periodontal sites. Infection control is the key to success, though it is the aspect of treatment that is most difficult to accomplish. The ultimate goal is durable restoration, both esthetic and functional, while attempting to avoid the use of partial dentures.

Currently, there is a strong incentive toward the application of evidence-based solutions and techniques. However, statistical analysis is more difficult to carry out in the clinical setting than in the context of pure research. Clinical practice can therefore demonstrate its efficacy and ultimately point out elements of scientific truth through interpretation of scientific information.

Among these indicators of clinical proof are the following:

• Continuous, progressive loss of periodontal support is a significant and undesirable clinical proof.

• Durable elimination of clinical signs of inflammation and long-term maintenance of periodontal support structures are significant positive clinical proofs.

• Attachment gain and reduced probing depths are significant, ideal clinical parameters that indicate long-term clinical success.

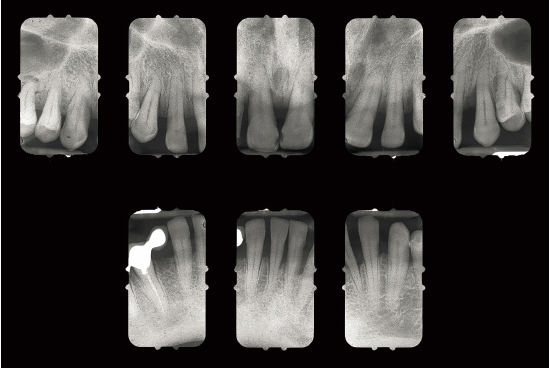

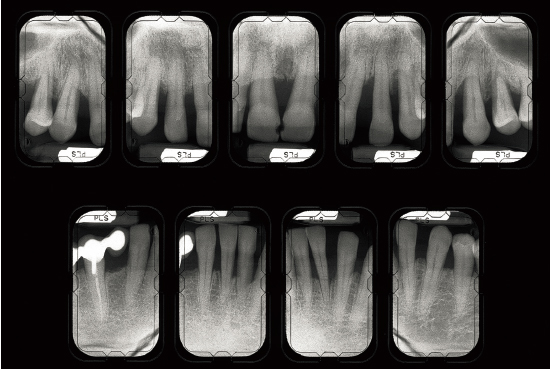

Fig 1-1a Aggressive periodontitis in a 40-year-old woman who is subject to stress and smokes one pack of cigarettes a day. The patient experienced an emotional shock 5 years earlier. A conventional treatment plan was initiated and included periodontal surgery throughout all quadrants. Professional maintenance (scaling and root planing) was carried out every 3 months, and the patient responded well.

Fig 1-1b Four years after treatment and maintenance therapy. Periodontal status has deteriorated in all areas. Observe the new attachment losses, dental migrations, and larger diastemata. It is clear that periodontal disease is not controlled. This patient’s disease was refractory to conventional treatment. Specific risk factors in this patient were underestimated.

Prevalence of Periodontal Disease

Periodontal disease predominantly affects the adult population. The overall prevalence of periodontitis is high. According to some authors, 90% of the general population have signs of periodontitis and 50% of individuals aged 15 to 19 years have at least one periodontal pocket (Waerhaug 1975; Sheiham 1978). An analysis of the natural history of the disease is informative and shows that there are several periodontal disease subtypes.

A first longitudinal study, carried out in a tea-picking community of Sri Lanka (Loë et al 1986), studied a group of individuals who were relatively well isolated from dental care over a period of 15 years. At the end of the study, the authors defined three groups:

• The first group represented 8% of all studied individuals and was characterized by the presence of a rapidly progressing form of periodontal disease. Approximately 20 teeth had been lost for periodontal reasons before the age of 40 years, and all teeth were generally lost at the age of 45 years (Figs 1-2a and 1-2b).

• The second group represented 81% of all studied individuals; this group featured a moderate form of periodontitis and an average of 7 teeth lost for periodontal reasons at age 45 years (Figs 1-3a and 1-3b).

• The third group represented 11% of the study group and was characterized by the absence of periodontitis; no teeth were lost to periodontal disease, and despite the presence of gingivitis, no evidence of periodontal destruction was observed (Figs 1-4a and 1-4b).

The results of this study were confirmed in other population groups. This distribution is considered valid in various populations, regardless of geographic localization.

In Western Europe, a study of nonedentulous individuals aged 45 to 54 years showed that 36% presented with a severe form of periodontitis, 31.9% had a moderate form of periodontal disease, and 32% presented no signs or symptoms of periodontal destruction (Ainamo et al 1982). It is noteworthy that edentulous cases were not taken into account. In France, according to a study by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), 90% of the general population presents with various degrees of periodontal pathology (INSERM 1999).

In Sweden, 13% of individuals examined in 1973 and reexamined between 1988 and 1991 displayed signs of advanced periodontal disease with bone loss of more than 20% in more than six anatomic sites. Most frequently involved were maxillary (18%) and mandibular (12.8%) premolars followed by maxillary first molars (13.5%). Risk factors associated with disease progression were also stated: presence of supragingival plaque, number of probing depths exceeding 4 mm at baseline, smoking, age, heredity, stress, sociologic factors, and presence of systemic disease (Norderyd et al 1999).

In a study carried out in the United States (Brown et al 1989). The authors reported that 15% of the investigated population presented no sign of periodontal disease and that 50% had gingivitis with no evidence of periodontitis. Moderate periodontitis, with probing depths between 4 and 6 mm, was found in 33% of the group. Advanced periodontitis, featuring probing depths exceeding 6 mm, was observed in 8% of patients and involved one to two teeth. Terminal periodontal destruction leading to tooth extraction was observed in only 4% of studied cases. Easy access to dental care and hygiene practices, and living in an economically advanced country, all reduce the prevalence of periodontitis.

A more recent study performed in the United States showed that approximately 35% of adults present signs of periodontal disease. They represent more than 60 million individuals, among which 12.6% have an aggressive form of periodontitis. Prevalence increases in males and in African American and Mexican communities (Albandar et al 1999).

In a study carried out in urban communities in the United States, Craig et al (2001) compared the prevalence of periodontitis in three distinct ethnic groups—Asian American, African American, and Hispanic American. The authors reported higher prevalence and severity of periodontitis in the African American community. This is correlated to limited access to private dental care and a higher smoking rate. Overall, clinical signs of periodontal disease are found to be more advanced in low-income households.

In conclusion, among individuals presenting with bacterial plaque and calculus due to poor plaque control:

• 8% to 15% are likely to develop an aggressive form of periodontal disease that will probably compromise their dentition in the absence of periodontal management.

• 60% of these individuals are likely to develop a moderate level of periodontal damage.

• 15% to 30% present no periodontal destruction despite the presence of gingivitis.

• Gingivitis does not always evolve toward periodontitis.

• Low socioeconomic indices, as well as certain biologic risk factors, seem to increase the risk for developing an aggressive form of periodontitis.

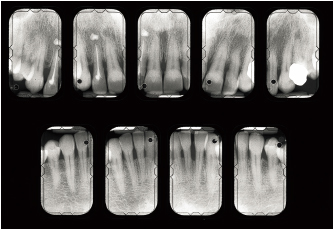

Fig 1-2a Aggressive periodontitis in a 50-year-old man. There is significant functional impairment; all teeth are mobile.

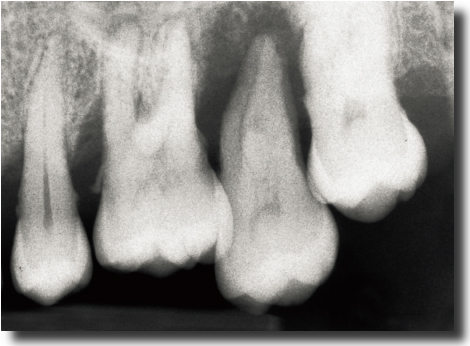

Fig 1-2b Destruction and attachment losses exceed 9 mm.

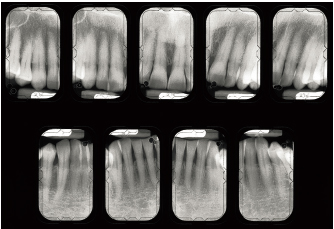

Fig 1-3a In this 40-year-old patient, periodontitis is moderate.

Fig 1-3b Destruction and attachment losses are evenly distributed throughout the dentition and are less than 30%.

Fig 1-4a This 77-year-old patient presents no sign of periodontitis, despite the absence of preventive care.

Fig 1-4b There is no evidence of periodontal destruction.

| Pathogenesis of Periodontal Disease |

|

Periodontal disease is an infectious disease caused by the presence of bacterial plaque (Timmerman et al 2001). Bacterial plaque is a nonmineralized accumulation of microbes that is able to adhere firmly to dental, restorative, and prosthetic surfaces. Bacterial plaque has been found to have structural organization. It cannot be displaced by mouth rinsing or by a high-pressure water spray (Listgarten 1994). Its growth is regulated by a dynamic balance between the oral microbiota and a number of factors that may either promote or inhibit the development of specific bacterial populations. Supragingival plaque essentially contains aerobic bacteria. In subgingival plaque, the proportion of gram-negative anaerobes increases.

Different forms of periodontitis have different bacteriologic etiologies. Features of periodontal disease are also determined by factors that modify host response or those that modulate individual host susceptibility, whether systemic, genetic, environmental, or acquired. These modifiers can activate or inhibit mechanisms involved in host response.

The protagonists of the response to bacterial insult are normally involved in tissue protection, but they also may be involved in the processes resulting in tissue destruction. This means that an episode of tissue regeneration may follow an episode of tissue destruction. From a treatment standpoint, this justifies the use of conservative techniques that utilize the potential for repair and regeneration, rather than using more aggressive, irreversible approaches in treating periodontal disease.

Biofilms and Bacterial Complexes

Three bacterial species seem to be involved in most forms of periodontal disease (except in necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis): Porphyromonas gingivalis, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, and Tannerella forsythensis (formerly Bacteroides forsythus). Intrafamilial transmission is possible and seems to be associated with individual susceptibility factors. When these bacterial forms are present, all the infected members of a given family carry the same clonal type. Usually, this same clonal type occurs in a given pocket, family member, and family (Socransky and Haffajee 1994). This has multiple consequences in formulating strategies for prevention and treatment.

Two fundamental features of bacterial plaque explain the difficulty in controlling its growth and eliminating it. First, subgingival plaque is organized as a biofilm and, second, the bacterial species it harbors interact specifically to form bacterial complexes.