1 Musical Execution Analysis

1.1 Background: The musical work and its appearing forms

1.2 Chosen Interpretations

2 Traditional Methods of Execution Analysis

2.1 Qualitative Description

2.2 Measuring and Data Recording

2.2.1 Absolute Tempo

2.2.2 Tempo Relations

3 New (Biopsychomusicological) Method of Execution Analysis

3.1 Time Series

3.1.1 Background

3.1.2 Time Series Analysis

3.2 Computer-Programme AlisOnda for Wave-File-Analysis

3.2.1 Parameters

3.2.1.1 Loudness-Change

3.2.1.2 Frequency-Spectrum

3.2.1.3 Tone Density

3.2.2 Analysis Results

3.2.2.1 Loudness-Change

3.2.2.2 Frequency-Spectrum

3.2.2.3 Tone Density

3.3 Chronobiological Methods

3.3.1 Periodicity

3.3.2 Regulation

3.4 Foresight

Literature

Under the term “musical work”, a composition should be understood, which exists as an interlaced structure of intellectual ideas on the mental level of a composer. It has different appearing forms at disposal: a structure on the mental level, a sounding structure while the execution and a written fixed form in the form of a sheet of music. In all these possible appearing forms, the musical work per se keeps being the same. The appearing form of the written text allows us to look at the whole work at once. Which part of the work we look at a certain moment is free to our choice, and depends not on the time. This not time-depending form is called an intentional state by Ingarden.1 Differently is the situation with the appearing form of the sounding process: this appearing form occurs in the time, at a time only one part of the musical work is present, and the whole work never appears simultaneously. The translation of the written text into a sounding process ties a time-independent appearing form to a time course. The musical work therefore is heard in a real state. The appearing form of the mental structure of the composer is also not time-dependent; it is a subjective system of relations. The significance of music can be determined as an embodiment of the relations between the tones which form the musical work.2

The text is therefore not equivalent with the musical work, but only one of its possible appearing forms. Horst-Peter Hesse formulated this thought very plausible: The score is not the musical work itself, but as a real object a complex sign, which symbolizes the intentional object musical work in form of a more or less perfect image.3

The fixation of a musical work by the composer from the form of the mental structure into a written form, with the limited musical resources of the score at disposition, represents by now a restriction. Here already a translation takes place; a translation from the original mental ideas into a written image which symbolizes these ideas. The relation between the prototype and the image in form of a written text has been appropriately described by Busoni: The notation, the down-writing of music pieces, is first of all an ingenious makeshift to record an improvisation in order to let it rise again. The latter behaves towards the first just as well as the portrait against the living model. The interpreter has to resolve the obstinacy of the signs and to set them in motion.4 Waltershausen even speaks in his Art of Conducting about the written text as a dead record which cannot exist without the human experience.5

At the execution of a musical work, an interpretation is necessary. Interpretation in the sense of translation, of understanding the meaning of the composer’s ideas which are behind the written musical symbols, into a sounding process. This sounding result should come as near as possible to the ideas of the composer.

That fore, the interpreter has to translate on the one side the written symbols of the music score (to reconstruct the original composition to which the score belongs as an image of it), and on the other to make clear to the listener the structure of the musical work, the complex network of internal relations, by his way of presenting the work.

During the execution, to the subjective system of relations in form of a mental structure, absolute quantities will be assigned to. The pitch (reference value for instance a1=442.7 Hz) ort he tempo (reference value for instance quarter note=116 bpm) are clear and unambiguous measurable units.

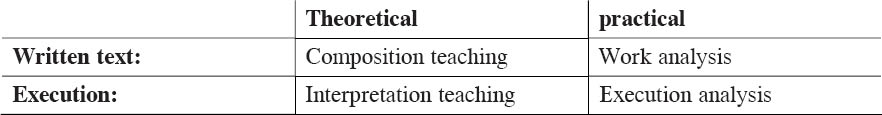

Depending on the appearing form of a musical composition, there are needed different methods and tools for the work out and analysis. Those tools directed to the written text have in the musicology already a long tradition, however for the area of the execution the tools are only in the initial stages. The two areas could be subdivided into a theoretical and a practical part, where the theoretical covers the considerations which deal with the origin, and the practical with the analysis of the object. According to that, the branch directed towards the appearing form of the written text would be subdivided into composition teaching and work analysis, and the one directed towards the appearing form of the execution into interpretation teaching and execution analysis.6

TABLE 1

|

Theoretical |

practical |

Written text: |

Composition teaching |

Work analysis |

Execution: |

Interpretation teaching |

Execution analysis |

One consequence of this would be hat the absolute tempo is not part of the work analysis, but is part of the execution analysis.

In order to apply the tools of the execution analysis, two contrasting movements of the 9th symphony by Antonín Dvořák were chosen. The second and third movement have both a special character, but among the interpreters exists not one exactly equal way of understanding and executing the pieces. Many different forms of interpreting them can be found. Differences are expected not only in the musical tempo, but also in other parameters.

The interpretations of the symphony no. 9 from Antonín Dvořák chosen for the analysis are listed in Table 2.

An interesting question arises out of the fact that three interpretations used for this analysis are from the same conductor and orchestra, played within eleven days.

TABLE 2