I Can’t Believe I Ended Up in Berkeley

Remembering a Country Boyhood

Ron Parker

ISBN (Print Edition): 978-1-54399-991-4

ISBN (eBook Edition): 978-1-54399-992-1

© 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Introduction

To know fully even one field or one land is a lifetime’s experience. In the world of poetic experience it is depth that counts, not width. A gap in a hedge, a smooth rock surfacing a narrow lane, a view of a woody meadow, the stream at the junction of four small fields—these are as much as a man can fully experience.

Landmarks, Robert McFarland

(Penguin Books: UK, 2016)

Most of my first eighteen years were lived within four square miles that encompassed the Parker farm and flour mill, stretches of Fleming Creek and the Huron River, the one-room Geddes School and the Dixboro Methodist Church. I shared that milieu with one great-grandmother, two grandparents, a great uncle and a great aunt, five uncles, four aunts, six cousins (two of which were double-cousins) a younger brother and sister and my parents. Even after I began to ride the school bus into Ann Arbor for junior high and high school, the formative parts of my life were still confined to that smaller world.

In many respects, the values, attitudes and perspectives of our rural context were a generation behind the rest of the culture. Every week or two we ventured into town for necessities or to sell pigs or weaner calves, but mostly, town was an exotic foreign land to be avoided. City kids had paper routes; we had traplines. Riding-horses were for rich people; ours pulled a wagon or a plow. They went to the symphony, we to dances at the Grange Hall.

I went to a small Methodist college that encouraged many of the perspectives and values I was raised with. Then, I moved to Berkeley in the Sixties. Even though this was a shock to my system, I found this new context congenial to my ways of thinking, enough so that I have stayed for more than fifty years.

In recent years, as I edge toward eighty, I find many of the attitudes and intuitions that were laid down in those early years resurfacing in my psyche. That foundation in a simpler time is still very much a part of who I am.

What follows is neither history nor biography. I’ve made no attempt to tell the whole story. It’s a loose collection of poems and stories—some brief, some more extended—I’ve written over a period of forty years or so. Some have been revised a bit to fit the style of this collection, but for the most part they are simply what I remember of the events that shaped me.

In preparing this memoir, I have stuck to facts except when facts refused to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it. Wherever liberties have been taken with names, dates, places, events, and conversations, or with the identities, motivations, and interrelation-ships of family members and historical personages, the reader is assured that they have been taken with due abandon.

Moonglow: A Novel, Michael Chabon, (Harper: New York, 2016)

Contents

Introduction

Speaking Plainly

Weeds and Words

Modifiers

Land of Opportunity

Arrowheads and Eagle Feathers

Grandpa’s Stories

Grinding

Two Views

Milking

Come On Up

Fourteen

Elder Brother

Failed Inheritance

The Family Line

Dreams of Mink

Roadkill Redux

Sacrifice

Oblivious

Parker Orchestra: Soundtrack of My Youth

Christmas

Promise of the Earth

Great-Grandma Pettibone

Geddes School

Class in English Class

Extra Credit

Parting Shot

Working Class

Downstream

Glen

The Old Snapper

The Night Grandpa Died

Settled Estate

Back Row: Great-Grandpa Pettibone, Grandma Parker, Great-Grandma Pettibone

Front Row: Great-Grandpa Parker, Great-Grandma Parker, Uncle Everette, Grandpa Parker

Speaking Plainly

I was raised

on short,

homely words.

We built houses,

farmed red clay,

mucked out the barn,

hunted rabbits

in lingo of

rural working folk.

When we spoke,

you knew

just what

we meant.

First in my family to matriculate

to the exalted realms of higher education,

I immersed myself in academia,

declared a major in philosophy,

then steeped my avaricious brain

in metaphysics and epistemology.

I earned advanced degrees

and learned the elevated discourse

of my cultured colleagues.

I always felt

like I was

faking it.

Now,

poems of

old age

reach back;

sparse words

speak straight

to simple

facts of life.

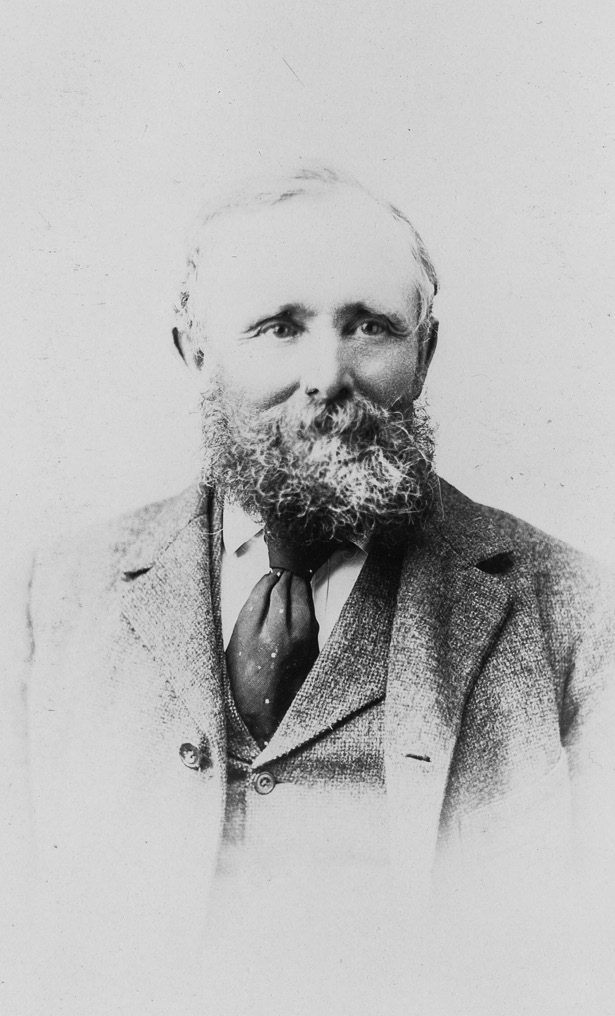

George Parker

Weeds and Words

Got weeds

in your planter box

again.

A gruff voice mutters from the photograph above my desk.

“I know.”

Better get ‘em out.

“No one else cares

or sees them.”

Shouldn’t be there.

A thin pane of wavy glass divides the weedy box on the deck outside from the clutter of the desk inside. On the wall, my grandfather watches from his own dark frame.

Weeds tell you

‘bout the character of a man.

“I’ve been meaning to get them out.”

Y’know where good intentions lead.

He lectures me on intentions. I’ve got a doctorate in philosophy, taught ethics in a university. He quit Geddes school after the sixth grade, worked on the farm. What does he know?

“They’ll just grow again.

Why you gotta’ keep after ‘em.

His life was a war on weeds. I see him, in low light of a summer evening, after the chores are done, family resting on the porch swing; he heads down the fence row to cut the hated bull thistles and burdock.

His scythe rests on his shoulder, it’s curving blade matching the contour of his bent back, the whetstone in the hip pocket of his blue overalls.

As shadows lengthen and dusk surrounds us on the screened-in porch, the solitary figure down toward the river slips from view. When it’s too dark to see beyond the well house, there’s a lull in the conversation, and we hear the gentle ring of the whetstone, sharpening the scythe before he brings it home.

“I’ll hire someone to do the yard

and weed the planter box.”

Never paid for nothin’

I could do myself,

that was pretty much everything.

“I guess that’s why

I haven’t hired anyone.”

One summer evening—I’m twelve years old—I follow Grandpa to the old ice-house where he keeps his tools, ask if I can help. He looks at me sharply, considers something, points to an old scythe hanging on a nail next to his.

Use that one.

Don’t cut your leg off.

I take it down, leery of its long thin blade.

Hold on.

Take this whetstone.

Keepin’ it sharp’s half the job.

I slide the well-worn whetstone into the hip pocket of my jeans, let him lead the way across the field to where he left off last night. The sharp smell of pipe smoke merges with the scent of dry wheat stubble. He is silent until we reach the fence.

You start here.

That scythe is good and sharp.

Keep it that way,

if you want to do any good.

I wait until he turns his back, watch the smooth and steady rhythm of his scythe leaving weeds and grass along the fence cut low and level.

I grasp the hand-grips on the long, curved handle, try to match his crouch, swing the unwieldly blade against dense weeds. A clunk and chilling scrape, the scythe nearly wrenched from my hands, announces that I’ve hooked it through the wire fence. Grandpa’s head jerks up. He chuckles, takes a long drag on his pipe.

Don’t cut the fence down.

Time to sharpen it already.

Here, let me take a look.

He runs his calloused thumb along the scary blade.

Yup, fence’ll dull it every time.

Where’s your whetstone?

I hand it to him; he stands the scythe up on its handle, blade extending out from under his left arm. He grasps the blade a foot from its end, strokes the stone on either side with rapid ringing rhythm.

Just work back up the blade that way

until you’ve done it all.

Watch your fingers.

Sharpening done, we work in silence, ten minutes at the most, my lower back begins to hurt. I wonder why he doesn’t rest. I stop, lean on my scythe. Grandpa looks, but doesn’t miss a stroke.

Big strong boy like you, I’d think

could swing a scythe all night.

I go back to work, until I need another rest.

“Why don’t you spray weed killer?

Wouldn’t have to cut the weeds.”

Don’t like weed killer.

Gets in the crops.

Costs money.

Scythe is free.

“The scythe is hard work.”

Somethin’ wrong with that?

We work until dark closes in and it’s too hard to see.

Time to quit, can’t tell

a bull thistle from a fence post.

I rest my scythe on my right shoulder, as I’ve seen him do, turn toward the house.

Hold on,

not done yet.

Never put a tool away

unless it’s sharp.

Side by side we play out a ringing duet of stone and steel, then walk back across the now dark field.

“It seems hopeless.

There are too many weeds

and too many fence rows.

Think you’ll ever get them all?”

He keeps walking, silent for a long time, seems older than I’d noticed. I wish I hadn’t said it.

Finally, he speaks.

Nope.

Prob’ly won’t ever get’m all,

but somebody will,

sometime, maybe.

Maybe he thought I was the one who’d keep the weeds down after he was gone. I took up books and words, left his antique blade, hanging from its rusty nail in the old ice house

Now weeds and dead marigolds fill the planter box outside my study window, distract me from my chosen work.

“I’ll take the box away.”

Maybe you should

move my picture then.

“That’s not fair.

I planted that box,

the whole back yard

because of you.”

Better keep ‘em up then.

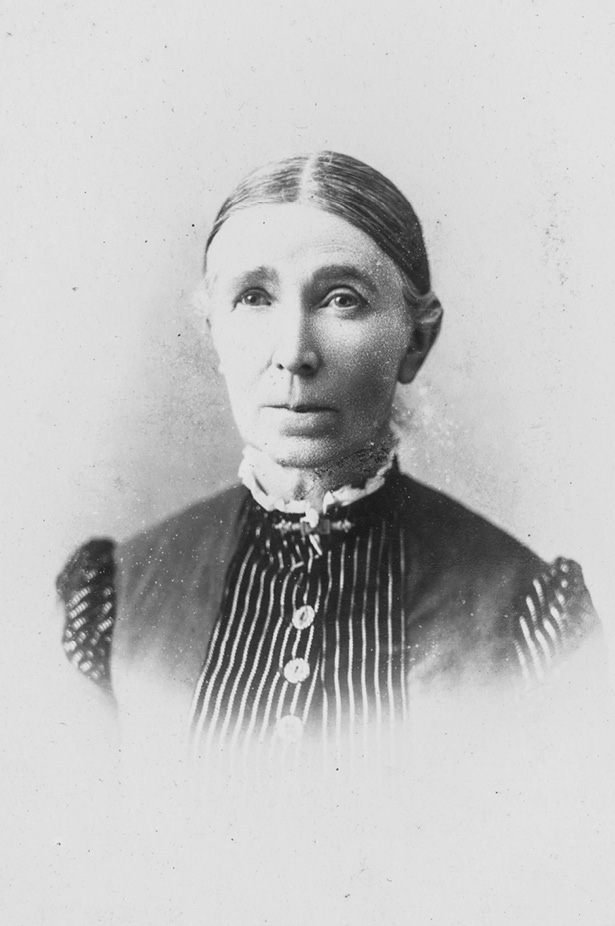

William Q. Parker

Mary L. Parker

Modifiers

Philosophers have only described the world in various ways; the point is to change it.

Karl Marx

William Parker, with wife Mary,

crossed an ocean, looking for a land

that they could form and build a life.

William cut down trees

shaped logs into a house,

cleared fields and carried off the stones,

so he could plow and plant.

Since Fleming Creek wound through his farm;

he dammed it up to make a mill, ground grain

so Mary, could transform it into bread.

Great-Uncle Fred,

found work with wood,

installed a wood-lathe

upstairs in the mill,

and turned the water’s flow

to porch pillars

for his father’s house.

When Fred left home,

he bought a forty-acre plot:

oak, ash, maple, and black walnut.

Felled trees with cross-cut saw,

hauled them with his team,

back to the saw-mill he had built.

He cut them into boards;

planed and shaved

and turned them on the lathe,

made his life by furniture

he shaped and sold.

My dad built houses:

first one for his bride, set on an acre

marked-out from the family farm;

next-door, another for his sister, Bessie.

Down by the river, another

for younger sister, Aunt Viola

and husband, Uncle George.

Grandpa and my Uncle Everette,

taught me how to work the land.

Dad and Uncle Fred

provided tools and wood.

The four of them taught me

that there was nothing

that I couldn’t grow or make,

given trees and soil and tools and will.

When I became a man,

I chose to work with words.

The logs I cut were nouns and verbs,

my tools their modifiers.

My vocation was to tell the truth, to unmask lies

about the world that we were given.

The nouns and verbs that we received

sometimes oppressed the poor,

demeaned women, excluded

those deemed foreign or divergent.

I sought to craft and till

those words for change.

But now my friend, the poet, asks me

to give up adjectives, adverbs,

those tools I’ve used to change

the given nouns and verbs.

Could William have raised wheat

between the trees that grew along the creek

or eaten oats straight from the stalk.

Imagine Uncle Fred, at rest

beside an unchanged oak,

his saw-mill rusting down the road,

lathe deprived of turning in the mill.

My father’s life was in his hands,

in making, changing, yes creating.

He could not abide accepting what was given,

died when he could no longer change it.

My family lived by changing what they found

until it fit their need. They taught me

how to do the same,

to love my nouns and verbs

for what they can become,

when modified

by skillful use of tools.