Copyright © 2019, Lois Legge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3660 Strawberry Hill Street, Halifax, NS, B3K 5A9

(902) 455-4286 nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

NB1397

Design: Jenn Embree

Editor: Angela Mombourquette

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

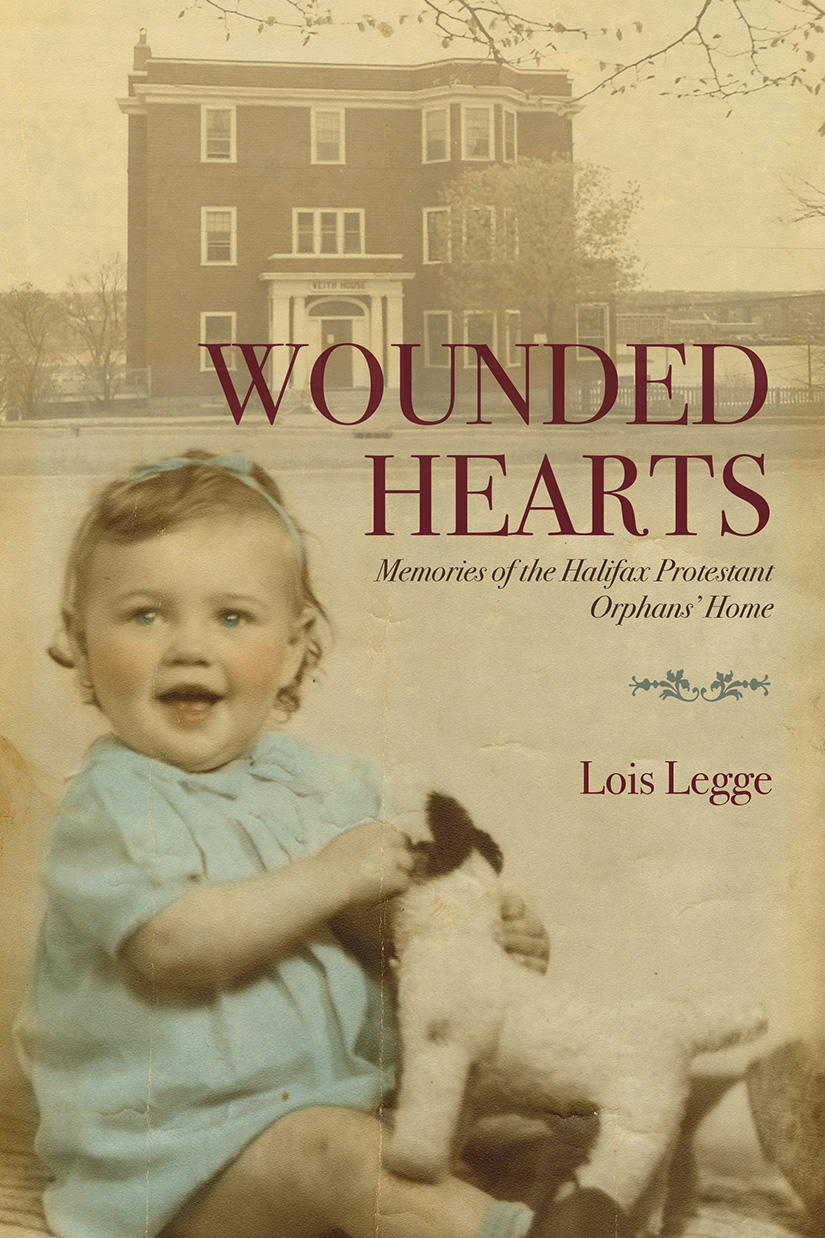

Title: Wounded hearts : memories of the Halifax Protestant Orphans’ Home / Lois Legge.

Names: Legge, Lois, author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: Canadiana 20190156899 |

ISBN 9781771087957 (softcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Halifax Protestant Orphans' Home—History. | LCSH: Orphanages—Nova Scotia—Halifax—History.

Classification: LCC HV1010.H352 H35 2019 |

DDC 362.73/2—dc23

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Province of Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians.

For Richard and Chelsea:

my heart, my home.

“It is because I think so much of warm and sensitive hearts

that I would spare them from being wounded.”

– Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist

I first heard about the Halifax Protestant Orphans’ Home from a reporter who was covering old bones.

Construction workers had found the remains while digging up a section of North Park Street and archeologists thought they might have been from a child. It had been the first site of what was later known as the Halifax Protestant Orphanage, founded in 1857 and closed in 1970. Forensic experts eventually determined they were animal bones, not the skeletons of children who had once lived in this forgotten place from another time.

Interest died down, and I tucked the story idea away for another day.

But hidden things often rise up—or never go away, as I’ve learned again and again from the former residents of this Halifax institution who were often beaten by staff members who scared them and taught them, as one person put it, “about the uncertainty of life.”

Today these former residents are senior citizens whose sons and daughters are grown, and whose grandchildren are growing or are about to be born.

But as I listened to them speak, I thought of them as children. I thought of their baby pictures and school photographs and old black-and-white snapshots taken inside the orphanage—a place for children who were neglected or abused at home, or whose parents had died, or whose parents were too sick or too poor to raise them. I remembered ringlets rimming tiny faces, and gap-toothed smiles. I remembered little bowties, worn for first communion, and tiny hands holding stuffed toys.

I wondered how anyone could ever strap them or keep them in closets or tie them to beds, as many say some of the matrons—the women who ran the orphanage—often did. I wondered how their parents or their foster parents could have beaten them or starved them or humiliated them, as some say their blood relatives and appointed guardians did.

I wondered how those who had been loved but had lost their parents to poverty or sickness or death had managed in this strange place of loneliness and fear.

And I wondered, after all of that, how they went on to build careers and loving families, and how they formed compassionate hearts out of the wreckage of their own.

It’s a daunting task to take someone’s life story into your own hands and try to tell it with truth and dignity and compassion—and to do it without adding to the hurt. But thinking about their lives as children made me determined to try.

And made me hope, in some small way, to help heal these wounded hearts of long ago.

The names appear like phantoms on paper, buried deep in tattered records from another time.

Bess Hooper, seven—died of unknown causes in 1859.

Sarah Churley, twelve—died of “some affection of the brain” in 1876.

Five children, unnamed—died of diphtheria in 1880.

Other orphanage “inmates” emerge as numbers—admitted or discharged, “adopted or claimed.”

Some of the Halifax Protestant Orphans’ Home’s past is long lost, stored only in the memories of survivors. Some of it is incomplete—details missing among these yellowed records, in faded folders, tied with string.

The collection of annual reports, financial records, meeting minutes, letters, and handwritten notes—stored at Nova Scotia Archives—includes sanitized or mundane versions of a time former residents describe as far more sinister. Although occasionally, in later orphanage records, glimpses of a darker reality also emerge.

The oldest of the documents are frayed now. And faded.

So fragile they can’t be photographed or photocopied.

So thin they sometimes crumble to the touch.

Most veil as much as they reveal about the “little waifs” who were “snatched as brands from the burning” and rescued by “their Heavenly Father’s love.”

What happened to these children—“little wanderers and little outcasts”—in the days of paupers and poor houses, of orphanages and asylums, of pity and piety?

No one will ever know. Most of their stories aren’t written down or remembered.

But for the founder of the privately run institution—overseen by an all-male board of governors and the “Ladies’ Committee”; staffed by all-powerful “matrons”—it’s a different story.

By most accounts, Robert Fitzgerald Uniacke was a kindly pastor who dedicated his life to helping the poor—especially poor children.

Whatever became of his orphanage later on, his intentions appear to have been good, if tinged by the evangelical fires of his faith and the traditions of the times.

Old records portray a man who worked tirelessly on behalf of those less fortunate than himself, including the adults he ministered and the children who eventually ended up in his orphanage.

He took over as pastor of St. George’s Church, a congregation that then encompassed a wide geographical area of Halifax, in 1825, and he remained until his death in 1870.

During that time, according to archival accounts, he displayed an unwavering dedication to the task—from leading decades-long expansions to his parish, to building schools for the poor, to founding other churches, and, eventually, to founding the orphanage.

As Canon Henry Ward Cunningham—the rector of St. George’s in the early 1900s—writes in his History of St. George’s Church, Uniacke’s ministry went well beyond the church. He tended to the poor and the sick, in a time and in a city often plagued by poverty and deadly disease.

“In 1834, Halifax was visited by the dreaded Cholera,” Cunningham writes in a lengthy manuscript, published as a series of articles over several years, in the church’s magazine.

Most people who could do so left the city but not thus did Mr. and Mrs. Uniacke forsake the sick and suffering, but remained at their posts, nursing, giving medicine, soothing the sufferer, comforting the dying.

…When the smallpox visited Halifax he turned the Rectory into a hospital and his stable into a medicine supply and clothing and bedding were given freely to all who needed them. He was both physician and nurse.

Uniacke came from a wealthy family of lawyers and judges—even a Nova Scotia premier. But he was also a strong proponent of education for the poor. Archival documents show he repeatedly sought, and received, government money to fund his schools, which catered to poor children of all denominations.

By the mid-1800s he and other prominent citizens, including prolific philanthropist Isabella Binney Cogswell, were seeking support for an orphanage, one of many in Halifax’s history.

The so-called “Orphan House”—built in the 1700s, and by historical accounts a run-down, rat-infested facility—preceded it. Other orphanages and homes for poor children followed, including St. Joseph’s Orphanage (a Catholic facility), St. Patrick’s Home for Boys (also Catholic), the Halifax Infants’ Home (a Protestant institution), The Home of the Guardian Angel (Catholic), and the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children. Other institutions were a combination of orphanage and reformatory.

Halifax also housed the destitute in institutions like the Halifax County Poors’ Farm—for “paupers” and “the harmless insane”—which opened in 1887. It later became the Halifax County Home and Mental Hospital.

Perhaps the most notorious institution of them all was a children’s reform school known as the Halifax Industrial School (see page 217), which historian Renée Lafferty-Salhany says was by far the worst children’s facility she came across while writing her 2012 book, The Guardianship of Best Interests: Institutional Care for the Children of the Poor in Halifax 1850–1960.

These nineteenth- and early twentieth-century institutions were of a time when society was starkly divided, says the author, by religion and by race, by rich and by poor. And they were also of a time when poor children, who often ended up in the orphanage, were not only pitied as unfortunate outcasts, but were also feared.

“These would definitely be children who were on the margins of society; these are poor kids. The ideals are kids who are kind of fat, plump little cherubic things, and definitely white,” Lafferty-Salhany, who is also a history professor at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, says in an interview.

But poor children, both black and white, were considered a potential menace to society.

“There’s a big concern…that when you have kids that are poor, kids that are undisciplined,…[that] they were going to grow up to become criminals and burdens on the state, so you wanted to put them in these institutions to train them for what they considered…a useful life.”

And as residents of the Protestant home would discover, this training often included harsh discipline or even manual labour when they were sent out to work as indentured servants.

From the beginning, a group of well-to-do Halifax citizens had helped Robert Uniacke raise money for the facility, which was known as the “Orphanage Asylum” during the fundraising stage. They also sat on the first, and subsequent, board of governors. William Cunard, son of shipping magnate Samuel Cunard, was an early and long-time board president. According to one orphanage document, he personally raised $16,497 for the running of the home. He also continued to contribute annually to the institution for many years—$50 or $100 during the time when the home was on North Park Street and its annual operating costs hovered around $2,000.

Doctors, judges, lawyers, and ministers made up the all-male board of governors, and they funded the institution in annual installments of ten, twenty, fifty, or seventy-five dollars. Other citizens chipped in between one and four dollars a year. Wealthy Halifax women, often board members’ wives, served on the Ladies’ Committee, which oversaw the operation of the home and fundraised as well.

These types of contributions continued years later when the home moved to its first Veith Street location, which was destroyed in the 1917 Halifax Explosion. By 1924, at its final location on the same street, the orphanage was still primarily funded by the facility’s board of governors and wealthy benefactors. As they had in the 1800s, parents who directly placed children there occasionally contributed small amounts.

Bequests and fundraising also aided the institution, as did a long-running money source known as The Murdock Fund, named after William Murdock, a wealthy banking magnate who had been on the orphanage’s board of governors in 1859, and who had left legacies to a host of Halifax institutions.

Off and on through the years, the City of Halifax contributed grants to the institution as well, but the provincial government became a core funder—and one of the most consistent sources of financial support—from the early twentieth century on, and its funding grew substantially over time, as did its placement of so-called “wards”—children under government care.

Records show that for many years, the province was second only to the board’s wealthy members as the primary source of funding.

As the years passed, the number of children placed there by the provincial government and various children’s aid societies rose too.

“It seems that the department of welfare [DCW] is getting more children than CAS [Children’s Aid Society] and most of the cases coming to us now are coming from the department,” notes a 1959 monthly Ladies’ Committee report.

Many handwritten notes also mention the “excellent cooperation” between these agencies and the orphanage, which, despite these close ties, still operated without the province’s supervision and had complete day-to-day control over the children.

This arrangement would turn out to be a key question for some former residents, who wonder why—given the province’s financial support—they were left to the mercy of the matrons, whose cruelty, they say, has left lifelong emotional scars.

Religion was closely tied to the institution from the start and is a key and unrelenting reference in reports that remain.

In the early years of the orphanage, the children attended St. George’s Church every Sunday, and according to one orphanage document, “special seats were built for them in front of the pews. The Rev. Mr. Uniacke was pastor.” The children received in-house Sunday school instruction as well.

The Ladies’ Committee said a prayer and read a Bible passage at the beginning of each monthly meeting. Their stated philosophy, along with providing shelter, food, and education, was to immerse the children in “Christian principles”—in preparation for life and death.

“There are now many good, honest and industrious young men and women who owe their present condition to the existence of this Institution,” they wrote in their 1879 annual report.

When it is remembered under what circumstances, for the most part, the children are taken in, the change which is effected is the more remarkable….Whilst the religious instruction which is instilled into them is so valuable in its effects, these children whose earthly course would evitably be downwards to the lowest depths of moral degradation, are “snatched as brands from the burning” to get a fair start for a good life with a knowledge of their Heavenly Father’s love, and of their Savior Jesus Christ.

…The very name “orphan” tells of the helpless and uncared for condition, and thus it is that the most solemn charge is laid upon all to be considerate of this class of their fellow-creatures.

The Ladies’ Committee of that era often sent orphanage children to live with adoptive or foster parents, requiring only a positive letter from their minister beforehand. Several reports cite glowing letters from adoptive parents and adopted children about how they had been brought up, with only occasional hints that all was not well for everyone, and they are all anonymous voices in the void: the children’s stories are told under the watchful eye or through the filters of their adult guardians—the Ladies’ Committee, their foster or adoptive parents, or the people to whom they were indentured.

“The committee have been much cheered by the receipt of several very satisfactory letters concerning children adopted, among them one from a clergyman who adopted a little girl twelve years ago, in which he speaks of her as being a good, kind, Christian girl,” the committee writes in 1881, a year in which seventeen of the children were adopted.

“They are in nearly all cases adopted as members of the family, and treated as such, loving and beloved,” they say in 1888.

The guardians of the orphanage and other institutions considered discipline, along with religious training—and in some cases, manual labour that would lead to menial jobs—a key part of their mission. Some children were indentured, apparently sent to work for the families and institutions that took them in. This was “very common” in the nineteenth century, says historian Lafferty-Salhany.

“One of the real faults of both foster care and institutions is that whatever they thought they were doing, in the end,…really what they were looking to do was find cheap labour,” she says.

“St. Paul’s Home for Girls was training them to become domestic servants; they’d take in laundry to raise money, washing curtains of well-to-do folks in Halifax, so…it’s very much in the economic interests of the city, of the institutions, of the foster parents to find kids to do cheap labour.”

It became less common as the century closed, and authorities started, at least in theory, to understand that children should be protected rather than exploited.

“If they’re doing it [by that time], they’re not admitting that they’re doing it,” Lafferty-Salhany says—a key distinction, given the experiences of kids who were essentially put to work by foster parents all the way up to the 1950s.

Bylaws adopted by the Protestant orphanage around 1886 stipulated that “in case of the decease of those by whom the child may be adopted, or upon its receiving any unkind and cruel treatment, inconsistent with terms of indenture, the Ladies reserve to themselves the right of resuming control over the children.”

It isn’t clear if, or how often, that happened. Almost universally, the former residents who’ve shared their stories here stress that authorities never personally asked how they were treated either inside or outside the orphanage.

Inside the orphanage, the head matron had complete control over how the children were treated, as did other matrons, until the institution closed in 1970.

The Ladies’ Committee spelled out the matrons’ duties in 1883. Among them:

“Full control of the children except during school hours.”

“To see that the children are always kept clean, that they are bathed twice a week, that their heads are regularly combed (combing to be done in the bathroom) and that their clothes are made and kept in order.”

“To have the bedding changed every Saturday morning.”

To be “very particular in attending to their habits, morals and manners…always being present with them at their meals, and see that they behave themselves properly.”

To visit the children’s rooms every night “to see that everything is safe and comfortable.”

The head matron and her husband were also required to attend church with the children every Sunday and to ensure they were trained “in the knowledge and love of the Lord Jesus Christ.” She was allowed one afternoon and evening off a week.

If a child’s parents were alive, they had no say in how the children were treated, as noted in the home’s constitution and bylaws of 1886: “No parent, guardian, or other person not officially connected with the institution shall interfere in any manner with the care or management of children while they remain in the home.”

Children at the Protestant Orphanage learned this again and again as the years passed and matrons came and went. Most of the matrons now long gone.

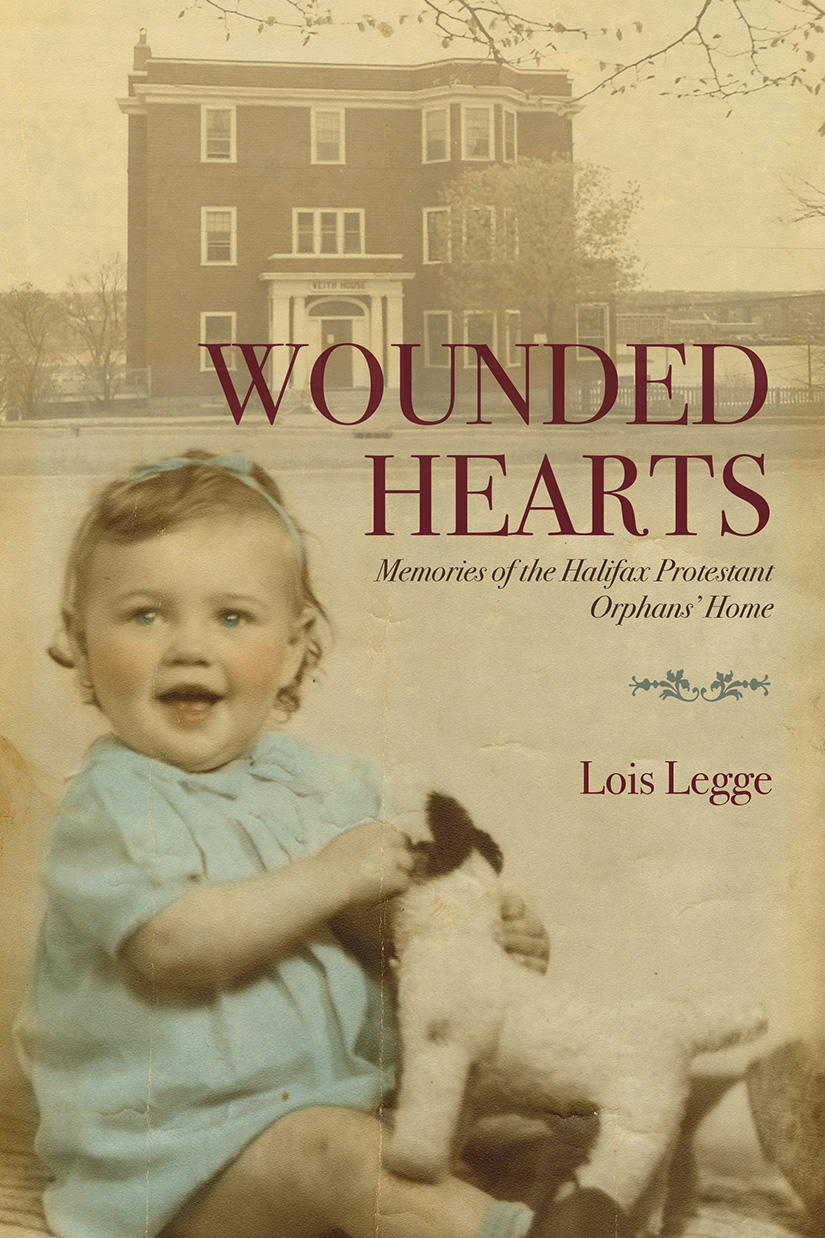

The orphanage began on North Park Street. But eventually the Ladies’ Committee pushed for a bigger building, in part to help stop the spread of diseases, and that led to the move to the first of two buildings the orphanage eventually occupied on Veith Street, within sight of Halifax Harbour.

“At present it is almost impossible to prevent diseases of an infectious and contagious character from spreading rapidly, and the necessity for better means of isolation must be evident to all who consider the character of the institution,” the committee wrote in 1874.

“Owing to the presence of the fever in the spring, so much inconvenience was experienced that the committee felt the necessity of representing the matter strongly to the governors and expressing it as their unanimous opinion that some prompt action should be taken with regard to it.”

The board and the committee eventually settled on buying a home that was at that time owned by one William Jordan, Esq.

“The house is large and airy, having an excellent basement and has been built with much care and expense,” the Ladies wrote in their 1875 annual report.“The grounds are extensive,” they noted. And a large playground ensures children “can get plenty of air and exercise without having to go outside of the confines of the institution.”

In the following year’s reports, they are reveling in their new premises and the fact it is “wonderfully free from epidemic disease”—“remarkable,” they say, “considering the character of the institution, or age and class of the children….

“During the year several improvements have been carried out regarding sanitary arrangements, and it may now be safely said that no building could have better guarantees of health and purity.”

But that was about to change.

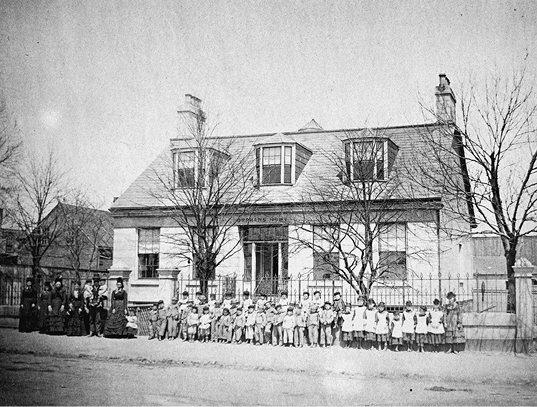

One of the biggest milestones in the home’s history arrived in a flash and a fury when the Halifax Explosion—the largest man-made explosion the world had ever known—tore through the north end of the city.

“On this site the Protestant Orphans’ Home stood until December 6th, 1917,” says a plaque that sits just a few steps away from the site. “On that fateful day the Halifax Explosion destroyed the orphanage along with nearly every other house on Veith Street.

“A story is told that after hearing the minor detonations that preceded the Halifax Explosion, the matron gathered twenty-six children and two staff in the orphanage basement. She thought the city was being bombed. Miraculously, when the building collapsed and burned after the catastrophic blast, seven children survived.”

The head matron, identified in newspaper clippings as Mary Knaut, died in the blast, as did assistant matron Ethel Melvin, housemaid Lena Meagher, and many of the children—who authorities said burned to death or were never found.

But it’s not clear, despite the plaque, exactly how many children survived. The numbers vary in different accounts. A 1919 letter from the Protestant Home’s secretary, M. Scott, outlines the challenges the institution faced in the aftermath.

“This home is striving to rise from its ashes, and amid many difficulties continues its work,” the secretary writes in the home’s yearly overview, contained in the 1919 Journals of the House of Assembly.

The terrible disaster of December 6th wiped this Home out of existence. Of the forty-one children then in the Home fifteen only survived the disaster. A temporary Home was secured in the extreme south end of the City, and in April 1918 the work was again taken up. This house is not suitable either in situation or accommodation and the matron has been handicapped in many ways.

…It is hoped in the near future a site may be secured.

By 1924 the home had been rebuilt in the north end, in a new building on the same street. That building is now a community centre known as Veith House.

The last of the children left that building in 1970 after Nova Scotia followed a North America–wide wave of de-institutionalization in favour of foster care—although that too, as the experiences of so many former orphanage residents can attest, was fraught with problems. Once again, authorities were “dealing a lot with the honour system,” says historian Lafferty-Salhany, meaning that foster parents were not held accountable for the care of the children. “And a lot of kids end up suffering.”

The depths of those kids’ suffering, in orphanages and elsewhere, was also becoming more widely understood, and there was a growing consensus about the psychological damage caused by institutionalization itself.

“Even where deliberate abuse was not in evidence,” Lafferty-Salhany writes in The Guardianship of Best Interests, “and where institutional staffs provided adequate and loving care for their charges, psychologists, doctors, and child welfare specialists have condemned the effects of institutionalization on the psychological and emotional well-being of children.”

Researchers were also learning about the widespread damage physical and emotional abuse can have on the body and on the mind, increasing the risk of everything from heart disease to depression.

Former resident Shirley Carter puts it simply: “It will last.”