co-constructing body-environments

vol. 17, no. 02

2020

the journal of IDEA: the interior design + interior architecture educators’ association

idea journal

co-constructing body-environments

vol. 17, no. 02

2020

the journal of IDEA: the interior design + interior architecture educators’ association

idea journal

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

idea journal

co-constructing body-environments

vol. 17, no. 02

2020

the journal of IDEA: the interior design + interior architecture educators’ association

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

03

frontmatter

about

IDEA (Interior Design/Interior Architecture Educators’ Association) was formed in 1996 for the advancement and advocacy of education by encouraging and supporting excellence in interior design/interior architecture education and research within Australasia.

www.idea-edu.com

The objectives of IDEA are:

1. Objects

3.1 The general object of IDEA is the advancement of education by:

(a) encouraging and supporting excellence in interior design/interior architecture/spatial design education and research globally and with specific focus on Oceania; and

(b) being an authority on, and advocate for, interior design/interior architecture/spatial design education and research.

3.2 The specific objects of IDEA are:

(a) to be an advocate for undergraduate and postgraduate programs at a minimum of AQF7 or equivalent education in interior design/interior architecture/spatial design;

(b) to support the rich diversity of individual programs within the higher education sector;

(c) to create collaboration between programs in the higher education sector;

(d) to foster an attitude of lifelong learning;

(e) to encourage staff and student exchange between programs;

(f) to provide recognition for excellence in the advancement of interior design/interior architecture/spatial design education; and

(g to foster, publish and disseminate peer reviewed interior design/interior architecture/spatial design research.

membership

Institutional Members:

Membership is open to programs at higher education institutions in Australasia that can demonstrate an on-going commitment to the objectives of IDEA.

Current members:

AUT University, AucklandCurtin University, PerthMassey University, WellingtonMonash University, MelbourneQueensland University of Technology, BrisbaneRMIT University, MelbourneUniversity of New South Wales, SydneyUniversity of South Australia, AdelaideUniversity of Tasmania, Launceston and Hobart University of Technology Sydney, SydneyVictoria University, Wellington

Affiliate Members:

Affiliate membership is open to programs at higher education institutions in Australasia that do not currently qualify for institutional membership but support the objectives of IDEA. Affiliate members are non-voting members of IDEA.

Associate Members:

Associate membership is open to any person who supports the objectives of IDEA. Associate members are non-voting members of IDEA.

Honorary Associate Members:

In recognition of their significant contribution as an initiator of IDEA, a former chair and/or executive editor: Suzie Attiwill, Rachel Carley, Lynn Chalmers, Lynn Churchill, Jill Franz, Roger Kemp, Tim Laurence, Gini Lee, Marina Lommerse, Gill Matthewson, Dianne Smith, Harry Stephens, George Verghese, Andrew Wallace and Bruce Watson.

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

04

frontmatter

publishing

© Copyright 2020 IDEA (Interior Design/Interior Architecture Educators’ Association) and AADR (Spurbuchverlag) and authors

All rights reserved.

No part of the work must in any mode (print, photocopy, microfilm, CD or any other process) be reproduced nor – by application of electronic systems – processed, manifolded nor broadcast without approval of the copyright holders.ISSN 2208-9217ISBN 978-3-88778-917-6

Published by Art Architecture Design Research (AADR): aadr.info. AADR publishes research with an emphasis on the relationship between critical theory and creative practice. AADR Curatorial Editor: Dr Rochus Urban Hinkel, Melbourne.

IDEA (Interior Design/Interior Architecture Educators’ Association)ACN 135 337 236; ABN 56 135 337 236

Registered at the National Library of Australia

idea journal is published by AADR and is distributed through common ebook platforms. Selected articles are available online as open source at time of publication, and the whole issue is made open access on the idea journal website one year after its date of publication.

idea journal editorial board

Dr Julieanna Preston, Executive Editor, Professor of Spatial Practice, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand

Dr Anthony Fryatt, Program Manager, Bachelor of Interior Design (Hons), RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

Dr Susan Hedges, Senior Lecturer, Spatial Design, School of Art and Design, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Dr Antony Pelosi, Senior Lecturer, Interior Architecture, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Dr Luke Tipene, Lecturer, School of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Professor Lois Weinthal, External Advisory Member, Chair of the School of Interior Design, Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada

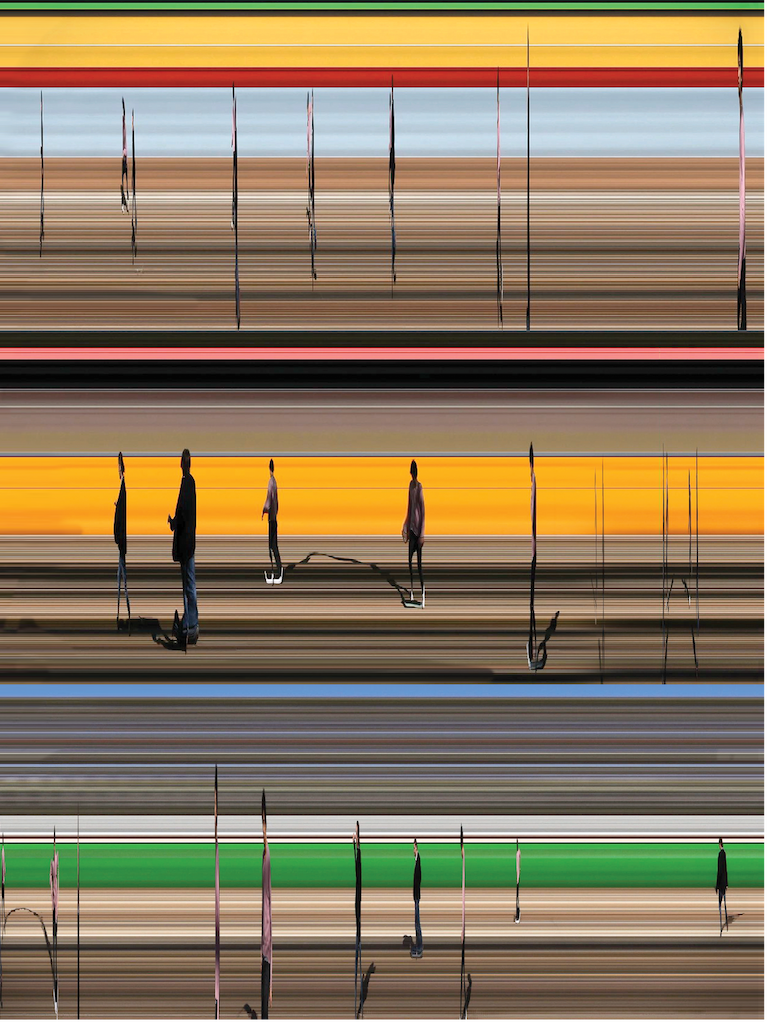

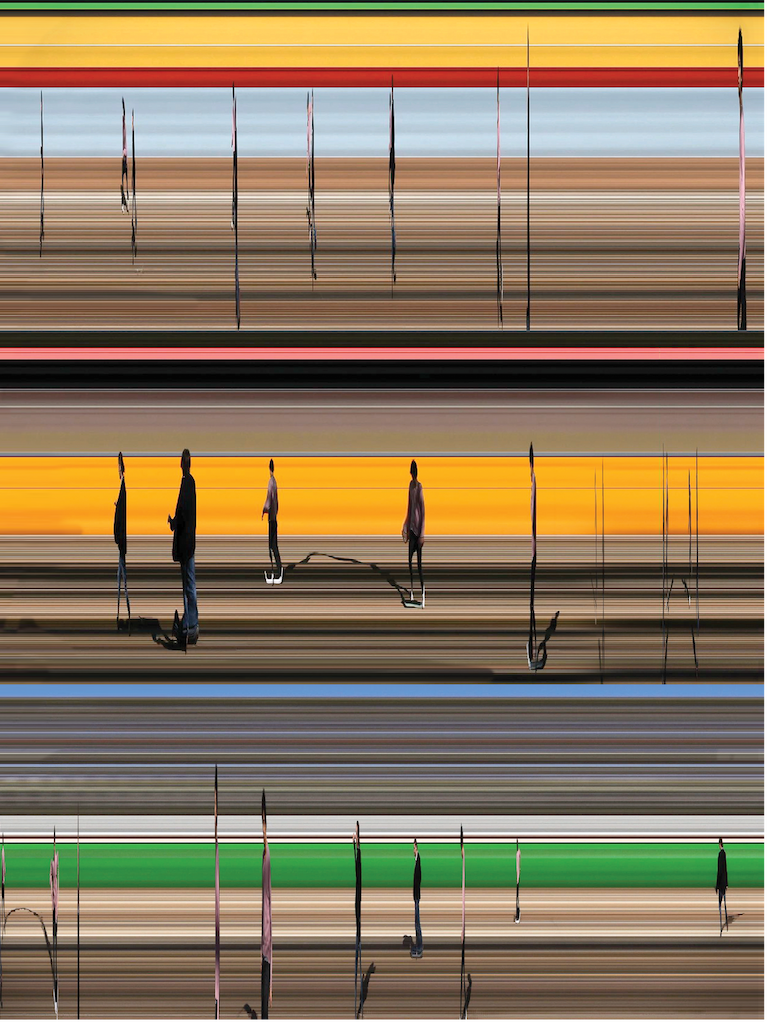

cover image

Animation by Jo Bailey (2020) of “Giacometti Strata, Bioscleave” (2015). Robert Bowen, Photographer

online publication editor

Dr Antony Pelosi, Senior Lecturer, Interior Architecture, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

copy editor

Dr Christina Houen, Perfect Words Editing

design + production

Jo Bailey, School of Design, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand

correspondence

Correspondence regarding this publication should be addressed to:

Dr Lynn Churchillc/o idea journalInterior ArchitectureCurtin UniversityGPO Box U1987Perth 6845Western Australia

l.churchill@curtin.edu.au

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

05

frontmatter

co-constructing body-environments: provocation

Presenters at Body of Knowledge: Art and Embodied Cognition Conference (BoK2019 hosted by Deakin University, Melbourne, June 2019) are invited to submit contributions to a special issue of idea journal “Co-Constructing Body-Environments” to be published in December 2020. The aim of the special issue is to extend the current discussions of art as a process of social cognition and to address the gap between descriptions of embodied cognition and the co-construction of lived experience.

We ask for papers, developed from the presentations delivered at the conference, that focus on interdisciplinary connections and on findings arising from intersections across research practices that involve art and theories of cognition. In particular, papers should emphasize how spatial art and design research approaches have enabled the articulation of a complex understanding of environments, spaces and experiences. This could involve the spatial distribution of cultural, organisational and conceptual structures and relationships, as well as the surrounding design features.

Contributions may address the questions raised at the conference and explore:

How do art and spatial practices increase the potential for knowledge transfer and celebrate diverse forms of embodied expertise?

How the examination of cultures of practice, Indigenous knowledges and cultural practices offer perspectives on inclusion, diversity, neurodiversity, disability and social justice issues?

How the art and spatial practices may contribute to research perspectives from contemporary cognitive neuroscience and the philosophy of mind?

The dynamic between an organism and its surroundings for example: How does art and design shift the way knowledge and thinking processes are acquired, extended and distributed?

How art and design practices demonstrate the ways different forms of acquiring and producing knowledge intersect?

These and other initial provocations for the conference can be found on the conference web-site: https://blogs.deakin.edu.au/bok2019/cfp/.

reviewers for this issue

Charles AndersonCameron BishopRachel CarleyFelipe CerveraHarah ChonChris CottrellDavid CrossRea DennisPia Ednie-BrownScott ElliottAndrew GoodmanStefan GreuterShelley HanniganMark HarveySusan HedgesJondi KeaneMeghan KellyGini LeeMarissa LindquistAlys LongleyOlivia MillardBelinda MitchellPatrick PoundRemco RoesLuke TipeneGeorge ThemistokleousRussell TytlerRose Woodcock

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

06

in this issue

06 in this issue

08 introduction: unknowingly, a threshold-crossing movement

Julieanna Preston

13 enacting bodies of knowledge

Jondi Keane

Rea Dennis

Meghan Kelly

32 ‘how do I know how I think, until I see what I say?’: the shape of embodied thinking, neurodiversity, first-person methodology

Patricia Cain

58 how moving is sometimes thinking

Shaun Gallagher

69 movement, narrative and multiplicity in embodied orientation and collaboration from prehistory to the present

David Turnbull

87 ‘stim your heart out’ and ‘syndrome rebel’ (performance artworks, autism advocacy and mental health)

Prue Stevenson

105 gentle house: co-designing with an autistic perception

Chris Cottrell

121 sympathetic world-making: drawing-out ecological-empathy

Pia Ednie-Brown

Beth George

Michael Chapman

Kate Mullen

144 shared reality: a phenomenological inquiry

Jack Parry

163 embodied aporia: exploring the potentials for posing questions through architecture

Scott Andrew Elliott

180 embodiment of values

Jane Bartier

Shelley Hannigan

Malcolm Gardiner

Stewart Mathison

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

07

201 sensing space: an exploration of the generation of depth and space with reference to hybrid moving image works and reported accounts of intense aesthetic experience

Sally McLaughlin

215 sound, silence, resonance, and embodiment: choreographic synaesthesia

Lucía Piquero Álvarez

230 musicking as ecological behaviour: an integrated ‘4e’ view

Michael Golden

248 everything of which I was once conscious but have now forgotten: encounters with memory

Mig Dann

265 re-presenting a dance moment

Ashlee Barton

275 hidden worlds: missing histories affecting our digital future

J Rosenbaum

289 is my body out of date? the drag of physicality in the digital age

Elly Clarke

326 seeing not looking

Anne Wilson

335 dance as a social practice: the shared physical and social environment of group dance improvisation

Olivia Millard

350 performance and new materialism: towards an expanded notion of a non-human agency

Alyssa Choat

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

08

introduction

julieannapreston

introduction: unknowingly, a threshold-crossing movement

Julieanna Preston

Executive Editoridea journal

It is in this special issue that the editorial board holds true to our promise to expand the horizons and readership of idea journal while reaching out to associated and adjacent art, design and performance practices and drawing connections to seemingly distant disciplines. The articles in this issue have provenance in a 2019 conference event, Bodies of Knowledge (BOK), which was guided by a similar interdisciplinary ethos. With an emphasis on cultures of practice and communities of practitioners that offer perspectives on inclusion, diversity/neurodiversity and disability, this conference, and this subsequent journal issue, aim to increase knowledge transfer between diverse forms of embodied expertise, in particular, between neuroscience and enactive theories of cognition.

This brief description suggests that there are shared issues, subjects and activities that have the potential of generating new understanding in cross-, inter- and trans-disciplinary affiliations and collaborations. My experience in these modes of inquiry points to the importance of identifying what is shared and what is not amongst vocabulary, concepts, pedagogies and methods. Holding these confluences and diverges without resorting to strict definition, competition or judgement of right and wrong often affords greater understanding and empathy amongst individuals to shape a collective that is diverse in its outlooks, and hopefully, curious as to what it generates together because of that diversity.

cite as:Preston, Julieanna. ‘Introduction: Unknowingly, a threshold-crossing movement,’ idea journal 17, no. 02 (2020): 08 – 12, https://doi.org/10.37113/ij.v17i02.412.

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

09

introduction

julieannapreston

The breadth of the knowledge bases represented within this issue necessitated that the peer reviewer list expanded once again like the previous issue. It was in the process of identifying reviewers with appropriate expertise that the various synapses between scholarly and artistic practices became evident. It is these synapses that shape sturdy bridges between the journal’s existing readership, which is predominantly academics and students in interior design, interior architecture, spatial design and architecture, and the wide range of independent scholars and practitioners, academics, and students attracted to BOK’s thematic call for papers, performative lectures and exhibitions. At the risk of being reductive to the complexity and nuances in the research to follow, I suggest that the following terms and concerns are central to this issue, aptly inferred by its title, ‘Co-Constructing Body-Environments’: spatiality; subjectivity; phenomenology; processual and procedural practice; artistic research; critical reflection; body: experience. All of these are frequent to research and practice specific to interiors. In this issue, however, we find how these terms and concerns are situated and employed in other fields, in other ways and for other purposes.

This is healthy exercise. To stretch one’s reach, literally and metaphorically is to travel the distance between the me and the you, to be willingly open to what might eventuate. Imagine shaking the hand of a stranger—a somatic experience known to register peaceful intent, respect, courage, warmth, pressure, humour, nervous energy, and so much more. This threshold-crossing movement is embodied and spatial; it draws on a multitude of small yet complex communication sparks well before verbal impulses ensue. This significant bodily gesture sets the tone for what might or could happen. Based on my understanding of the research presented in ‘Co-Constructing Body-Environments,’ I propose that this is a procedure in the Gins and Arakawa sense that integrates theory and practice as a hypothesis for ‘questioning all possible ways to observe the body-environment in order to transform it.’01 I call this as unknowingly—a process that takes the risk of not knowing, not being able to predict or predetermine, something akin to the spectrum of ‘throwing caution to the wind’ and ‘sailing close to

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

10

introduction

julieannapreston

the wind’. My use of the word ‘unknowingly’ embraces intuition where direct access to unconscious knowledge and pattern-recognition, unconscious cognition, inner sensing and insight have the ability to understand something without any need for conscious reasoning. Instinct. The word unknowingly also affords me to invoke the ‘unknowing’ element of this interaction—to not know, to not be aware of, to not have all the information (as if that was possible)— an acknowledgement of human humility. I borrow and adapt this facet of unknowingly from twentieth-century British writer Alan Watts:

This I don’t know, is the same thing as, I love. I let go. I don’t try to force or control. It’s the same thing as humility. If you think that you understand Brahman, you do not understand. And you have yet to be instructed further. If you know that you do not understand, then you truly understand.02

Unknowingly also allows me to reference ‘un’ as a tactic of learning that suspends the engrained additive model of learning. Though I could refer to many other scholarly sources to fuel this concept, here I am indebted to Canadian author Scott H. Young’s pithy advice on how to un-learn:

This is the view that what we think we know about the world is a veneer of sense-making atop a much deeper strangeness. The things we think we know, we often don’t. The ideas, philosophies and truths that guide our lives may be convenient approximations, but often the more accurate picture is a lot stranger and more interesting.03

In his encouragement to unlearn—dive into strangeness, sacrifice certainty, boldly expose oneself to randomness, mental discomfort, instability, to radically rethink that place/ your place/ our place, suspend aversions to mystery—Young’s examples from science remind us that:

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

11

introduction

julieannapreston

Subatomic particles aren’t billiard balls, but strange, complex-valued wavefunctions. Bodies aren’t vital fluids and animating impulses, but trillions of cells, each more complex than any machine humans have invented. Minds aren’t unified loci of consciousness, but the process of countless synapses firing in incredible patterns.04

In like manner to the BOK2019 conference which was staged as a temporally infused knowledge-transfer event across several days, venues, geographies and disciplines, I too, ingested the materials submitted for this issue in this spirit of unknowingly. The process was creative, critical, intuitive, generative and reflective—all those buzz words of contemporary research—yet charged with substantial respect and curiosity for whatever unfolded, even if it went against the grain of what I had learned previously. For artists, designers, architects, musicians, and performers reading this journal issue, especially academics and students, this territory of inquiry may feel familiar to the creative experience and the increasing demands (and desires) to account for how one knows what one knows in the institutional setting. ‘Explain yourself,’ as the review or assessment criteria often states. If you are faced having to annotate your creative practice or to critically reflect on aspects that are so embedded in your making that you are unaware of them, I encourage you to look amongst the pages of this journal issue for examples of how others have grappled with that task such that the process is a space of coming to unknow and know, unknowingly.

Figure 01:Meeting the horizon; A still image from Shore Variations, a 2018 film by Claudia Kappenberg that reimagines Waning, a 2016 live art performance by Julieanna Preston. https://vimeo.com/user11308386.

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

12

introduction

julieannapreston

There are a few people I would like to acknowledge before you read further. First, huge gratitude to the generosity of the peer reviewers, for the time and creative energy of guest editors Jondi Keane, Rea Dennis and Meghan Kelly (who have made the process so enjoyable and professional), for the expertise of the journal’s copy editor Christina Houen and Graphic Designer Jo Bailey, and to AADR for helping to expand the journal’s horizons.

Okay, readers, shake hands, consider yourself introduced, welcome into the idea journal house, and let’s share a very scrumptious meal.

acknowledgements

I am forever grateful for what life in Aotearoa/ New Zealand brings. With roots stretching across the oceans to North America, Sweden, Wales and Croatia, I make my home between Kāpiti Island and the Tararua Ranges, and in Te Whanganui-A-Tara/ Wellington. I acknowledge the privilege that comes with being educated, employed, female and Pākehā, and the prejudices and injustices that colonialism has and continues to weigh on this land and its indigenous people. I am committed to on-going learning and practicing of Kaupapa Māori.

notes

01 Jondi Keane, ‘An Arakawa and Gins Experimental Teaching Space; A Feasibilty Study,’ INFLeXions 6 (2012), accessed 29 October 2020, http://www.inflexions.org/n6_keane.html.

02 Alan Watts, Creating Who You Are (Video) (n.d.), accessed 29 October 2020, https://vimeo.com/76888920.

03 Scott H. Young, ‘The Art of Unlearning’ (2018), accessed 29 October 2020, https://www.scotthyoung.com/blog/2018/04/12/the-art-of-unlearning/.

04 Young, ‘The Art of Unlearning.’

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

13

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

enacting bodies of knowledge

Jondi Keane

Deakin University

0000-0002-6553-3313

cite as:Keane, Jondi, Rea Dennis and Meghan Kelly . ‘Enacting Bodies of Knowledge,’ idea journal 17, no. 02 (2020): 13–31, https://doi.org/10.37113/ij.v17i02.407.

keywords:practice-led research; enaction; embodied cognition; diversity and inclusion; interdisciplinarity

Rea Dennis

Deakin University

0000-0002-6214-3504

Meghan Kelly

Deakin University

0000-0002-2839-5943

abstract

This article discusses a range of issues that arise when bringing together researcher-practitioners around the intersection of art and science, body and environment. Although prompted by the issues raised at the second international Body of Knowledge: Art and Embodied Cognition Conference, the article addresses over-arching concerns around transfer of knowledge that are played out at conferences, through exhibitions and performance, and in publications.

The researchers of embodied cognition and arts practitioners/performers share a fascination with the way cognitive ecologies emerge to reveal the modes of thinking, feeling, moving and making that enact features of our shared environment. While theorists explore how enactive theories of cognition observe and track these dynamic changes, practitioners tend to reflect upon the changes their practice initiates. The intersections of these diverse research approaches that co-exist on common ground, highlight the need for space and air to allow tensions, blind spots, opportunities and potentials for knowledge production to become perceptible; to spark productive conversations.

This article considers the conference as an instance of enactive research in which communities of practice gather in an attempt to change encounter into exchange. In this case, the organisational structure of the conference becomes a critical design process that enacts an event-space. Consequently, if the event-space is itself a research experiment, then conferral, diversity, inclusion and cultural practices become crucial qualities of movement to observe, track and reflect upon. The activities within and beyond the conference indicate the extent to which creative research platforms alongside embodied enactive research projects must collaborate to draw out the resonances between diverse modes of acquiring knowledge and co-constructing the environment.

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

14

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

This special, guest-edited journal issue occurs at the fortuitous alignment of concerns shared by The Body of Knowledge: Art and Embodied Cognition Conference (BoK2019)01 and the idea journal, with its focus on spatiality and interiority. Honouring the ethos of the conference, the issue draws together eclectic, interdisciplinary, creative practice research. This introduction addresses the process of bringing these works into the journal and points to the alignments and aspirations of both the conference and the special journal issue. To that end, we address the tension that runs though, across and beyond the two modes of disseminating research: a conference and a journal. The overarching issues include the status of practice-led research and the value it is assigned in relation to other modes of enquiry, knowledge acquisition and production.

As scholars and practitioners who draw upon numerous creative methods that involve community engagement, we, the guest editors, feel it is important to outline and address the intersection of challenges which are made evident in these two interrelated yet distinctive events. In doing so, we will make a number of claims regarding the contexts and relationships of the diverse perspectives and the cultural practices on which they draw. Through this, we aim to advance on the conference proceedings to highlight the ecosystems within which practice-led research occurs, including creative industries, academia, social, cultural, and geo-political, so that the impact of the arts becomes apparent and transparent. Using systems theorist and polymath Gregory Bateson’s famous definition

of information, we might go as far as to say that ‘art,’ or more precisely, creative practices, is the ‘difference that makes a difference.’ Bateson states:

The explanatory world of substance can invoke no differences and no ideas but only forces and impacts. And, per contra, the world of form and communication invokes no things, forces, or impacts but only differences and ideas. (A difference which makes a difference is an idea. It is a ‘bit,’ a unit of information).02 [emphasis added]

In a later essay, Bateson opens this definition to all information; in ‘Form, Substance, and Difference,’ he states, ‘The technical term ‘information’ may be succinctly defined as any difference which makes a difference in some later event.’03 At the turn of the last century, Marcel Duchamp, painter turned conceptual artist, deftly demonstrated, by renaming and exhibiting the ready-made urinal, Fountain (1917): calling something ‘art’ imports an entire context, set of social practices, and readings that significantly alter the context of a space, object or relationship. Even the artist’s signature destabilises the identity boundaries of convention, where the pseudonym ‘R. Mutt’ operates across several registers: designating false authorship, symbolising the status of the art object as a cross-breed mutt, and requiring the meaning of the work to be surmised by looking outside the object at the object-context relationship. Yet not all art seeks to reveal meaning. Art making and creative practice also engender inquiry and enable us to question

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

15

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

assumptions about meaning and what constitutes knowledges.

Art provides a threshold concept for joining and separating ideas, contexts, histories, material qualities, and varieties of experience. Hence, when art is studied through the lens of embodied cognition, it triggers a difference within an existing set of relationships. The alteration, although perhaps imperceptible, results from the maker setting into motion myriad processes—participant, viewer and community. Because art is a fluid concept that both initiates change and also designates a category of activity, its impact cannot be reduced to a single variable, but must be understood as one amongst many. In effect, art is always the indication of an ecology of practices that touches upon, entangles with, and affects many fields of activity and enquiry. Such an ecology arises from the intersection of communities of practice and diverse perspectives. As a result of its slippery and generative capacity, Art allows complex conditions and relationships to emerge which cannot be pre-stated in advance. Therefore, when invoking art to qualify a set of relationships, one must accept the risks of collective and collaborative meaning-production and of singular interior experiences of meaning. How knowledge is acquired is as important as how it operates and is used, which is precisely what is at stake when embarking on practice-led research.

Embodied practices are cultural/enculturated practices. Research on social cognition, intersubjectivity, and embodied cognition offers vital connections between research that

observes and describes versus research that participates and reflects upon the conditions with which a research project engages. One of the issues that arises when art intersects with the academy is how art attains a value as research. If, as Bateson suggests, the bit of information that art represents is an idea, or perhaps more accurately, a proposal about the use of concepts, it is our assertion that, rather than allow a concept to operate solely in its home discipline, creative practitioners deploy concepts as creative devices. Depending on one’s point of view, this is either innovative and indicative of lateral thinking, or a derivative and superficial use of ideas out of context. As a result, art practice is often the subject or object of research, perhaps providing questions for further study, rather than contributing to other discourses such as philosophy, social sciences or cognitive science, which often discuss art, artworks and artists.

It is still contentious to align art with research, as art has been under-utilised as a mode of acquiring and producing knowledge. Increasingly, contemporary art and creative processes are becoming a way of understanding the impact of histories on meaning-production and working out the extent of the impact in situ. However, even the art community is divided on where knowledge sits in relation to art practice, disputing whether it resides in the form of research such as ‘practice-based’, ‘practice-led’ or ‘practice as’ research. These disputes arise along lines of cultural identities, education systems, and art history, playing out their biases within culture. Yet, over the past four decades,

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

16

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

there is a growing body of scholarship arguing that art-based research, material thinking, and embodied knowledge should be regarded as equals in the academy (Butt, Roger and Dean, Barrett and Bolt, Ingold, Kershaw and Nicholson, Pink, McNiff).04 This counterbalances prominent voices such as James Elkins,05 who would argue against the knowledge that art offers when considered as a research project contributing to a knowledge economy. Artist Patricia Cain addresses Elkins’ scepticism of art as research in her BoK2019 keynote06 and subsequent essay (included in this issue) in which she discusses her personal interaction with Elkins’ critical response to her PhD and subsequent book.07

As already noted, there are many reasons why the arts have a dysfunctional relationship with historical modes of research.08 What must be considered is how creative practitioner-researchers approach research and investigation—the processes, material and spatial engagements, as well as the values and metrics they deploy and the position they assign themselves in the enquiry. In contrast, philosopher Evan Thompson, in his keynote address at the Body of Knowledge Conference in 2016 (held at UC Irvine), understands that art plays a valuable role in knowledge production through a cognitive ecology in which ‘cultural practices orchestrate cognitive capacities and thereby enact cognitive performances.’09 Thompson notes that the motivation for his talk was to

draw attention to these [existing practices of mindfulness in the arts] and the need for a research collaboration

between the kind of expertise embodied in these practices and cognitive science10 and emphasising that ‘these practices need to be brought into the fold of cognitive science research on mindfulness practices.11

Thompson’s concluding remarks reinforce the call for multidisciplinary research collaborations:

What I am envisioning is not that they [mindfulness movement practices in the arts] just become another object of study—though that can be part of what happens—but they embody a kind of expertise; the practitioners embody a form of expertise—that is itself a form of investigation and research and that it needs to be on an equal footing with cognitive science because the tendency in our culture is to valorise and prioritise the science, and I don’t think that is going to do justice to what we want to do.12

What has yet to be fully implemented is the way to recognise a common footing for art in relation to cognitive science. Thompson advocated for more transparency, greater co-operation, and for a slowing down, in order to ensure that research projects are multidisciplinary, suggesting that participants in any research project should go out of their way to identify diverse roles and perspectives, and include an ethnographer who would keep track of knowledge practices throughout the development of the research. Drawing upon Thompson’s insights, we assert that

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

17

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

a rationale for the value of multidisciplinary research projects can be found in research on embodiment. That is, a cognitive ecology such as a research culture is a dynamic and precarious system in which attention is paid to the way any change in the system affects all the relationships in the system. A single disciplinary perspective is not adequate to address the complexity of human behaviour, perception and action, and a slowing down optimises subtle observation and durational knowledge production. Slow is critical when aiming to critique hegemonic practices, particularly at the level of the institution.13 Slowing down also opens spaces for non-linguistic meaning making that is central to aesthetic experience and aesthetic knowledge production.14 Pink champions visual and sensory ethnographic research, which has gained traction due to its emergence from visual and kinaesthetic artistic practices.15 The imperative—not to reduce life to a series of isolated fragments—is an approach through which enactive theories of cognition align with creative arts practices. Thus, the aim is to valorise what Sheets-Johnstone16 terms the moving body thinking, or as Beverly Farnell 17 suggests, the body as something to think from rather than to think about.

Research that involves thinking through making and making through moving and performance demands a critical engagement between, within, and around the practitioner, the creative outcome, and the context. Each configuration has a role to play in our understanding of new knowledge. Writing about research in art and design, Maarit Mäkelä emphasises the central importance of

the process in practice research, stating:

The product of making—i.e. the artefact created in Art and design practice—is conceived as having a central position in the research process. In this context, the artefact can be, for instance, a painting, a photograph, a designed object, a composition or a dance performance.18

Therefore, the Body of Knowledge Conference and this special issue of idea journal allows communities of practitioners across all fields to connect with and contribute to the field of cognitive research which has been discussed and debated internationally across the fields of art, including dance, theatre, music, fine and applied arts and design.

the site of spatiality: conference as an interdisciplinary practice environment

The next significant issue to consider is spatiality, and the place and motions that set knowledges into action and orchestrate the visibility of diverse knowledge practices. Australian Aboriginal knowledge is premised on a deep connection to the land on which they live. Understood through their bodies and linking them back through their ancestors, their relationship to the land is material, cultural and spiritual.19 Situating the conference at the Burwood campus of Deakin University entangled the event and the researchers and delegates who gathered within this way of knowing and invited a particular attention to the valuing of the differences within and across the way cultures conserve and enact knowledge.

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

18

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

In this way, the conference attempted to foreground the unique expression of the lived knowledges of Indigenous Australians through what is referred to as an Acknowledgement of Country. There are a great number of acknowledgements used in Australia with variation in length, tone and sentiment. Situated on the land of the Wurundjeri people, the conference gathering at Deakin University’s Burwood campus acknowledged that the present site of the Melbourne Burwood Campus is located on the land of the Wurundjeri people. They belong to these lands, have walked on them for thousands of years, and continue to care for them and nurture them.

Performing the acknowledgement highlighted the intersection of time, place and cultural knowledges. While such actions do not erase the history of violence that is intrinsic to the Australian national identity, they do serve to recognise the entanglement of ancient knowledge and the deep connection and affect that gathering collectively can activate. The acknowledgement performs a certain set of attentions and as Ingold identifies, foregrounds culture as the origin of the forms, and nature as the provider of materials.20 Performing the acknowledgement also acts to witness the way in which knowledge is a layering of events, actions, experiences, and encounters across and over time, and that knowledge is not just linked to the human condition nor to social contexts. The action engenders an affective ripple which enacts and draws attention to our collective experience as bodies. Feeling builds on this affect and accumulates as layers of knowledge

that inform practice research, which are also transformed by ongoing and repeated practice-based exploration. Such is the lived experience in art and design where affect bubbles up through our visceral perception, through what Clough terms ‘the sensate body.’21

Artistic practice as research articulates the body as the form through which insights are expressed. Through movement, gesture, sensing and feeling, this non-word mode of knowing is expressed through skilled hands, bodily awareness, or the highly trained bodies that have accrued knowledge through a discipline of practice over many years. The material body offers a source of positive knowledge, a site of active change. The knowledge that accrues over time with attention to embodied somatic practice is not singular. It interacts with itself in the body and with the body in the environment. It is recognised body to body but not when it is looked for or at, so much as when it is felt, and felt for. In movement practices, this knowledge forms as a material sediment in somatic form and acts to make the world my body. Just as the feeling of morning seeps into us as we walk, such knowledge accumulates and aggregates into a personal and unique praxis that is ‘arrived at through extremely high levels of creative synthesis, as well as spiritual, emotional, aesthetic, and political individuality.’22 Yet, this knowledge is so often out of reach as we have become increasingly sedentary, adapted to indoor and virtual worlds and disconnected from nature and the haptic and tactile knowledges of a material relational existence. The conference

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

19

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

set out to interrogate this state through a focus on noticing: to follow the sun; to sit by the window, to walk outdoors within the dynamic peripatetic sessions on offer; to practise honouring the ways we know that resist linguistic translation; and to value the labour of the writer, behind which are situated the labour of the artist, the researcher and of the artist as researcher. In creating conditions to facilitate sensory experiences in this way, The Body of Knowledge Conference 2019 interrogated the intersection of the capacity of theories of cognition to describe body-environment systems and the capacity of practice research to enact, materialise, instantiate and contextualise the potential of enactive descriptions. In this way, the conference was construed as an interdisciplinary practice environment that folded together the space of conferral, modalities of presentation and display, and the potential for further research.

the site of intersection: conference as an interdisciplinary practice environment

At the heart of this discussion, and central to this journal issue, is the way in which the experience of the creative practitioner-researcher sits precisely at the intersection between descriptions provided by theories of cognition, particularly enactive theories, and experimental production of enactive systems and relationships produced by arts practice and research. In the study of embodied cognition, art can be considered as an enactment of complex affective fields in which embodied, embedded, expanded, situated, and distributed modes are more

perceptible, and therefore more accessible to be studied. Importantly, the creative practice researcher enacts these explorations in non-reductive, real time experiments. A creative-practice approach to experimentation aims to learn from the production of difference and ongoing feedback in the dynamic system of practice—that is to say, the art-life project. The art-life project might be characterised as an unwillingness to consider the concerns that are focused upon in art practice as separate from those which bear upon the ‘realisation of living’ (the subtitle of Maturana and Varela’s 1980 book Autopoiesis and Cognition).23

Creative practices are said to exploit perception as action through what Alva Noe calls the ‘strange tools’24 of art that enact, inflect, modulate, circumvent, appropriate, and repurpose the embodied processes. When combined with observation and reflection, the knowledge acquired from participant-practitioner-researcher is of a different order and partakes in a different idea of what it means to assign value, to collectively select the features of an environment and co-construct shared meaning. For example, Shaun Gallagher’s keynote presentation at BoK2019 included a discussion of what is called ‘marking’ in dance where a person rehearses a set of movements in a dance sequence by minimising the movement range and speed.25 The bodily movement prompts a muscle memory and visualisation that allow the person to further entrain the movements, sequences, spatial arrangements, and qualities of movement into the body-person-environment. When a dance piece is ‘marked’ with other dancers, the activity

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

20

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly

research paper

serves to align and attune movements across bodies collectively projected into a performance space. In these circumstances, the dancers’ movements are more than the limited gestures they perform and call to the foreground a huge amount of knowledge that, in its squeezed and reduced form, is ready to unpack and expand into full-scale, full-speed performance mode. These ideas were deliberately applied to the conference through the way we integrated activities to foster engagement with embodied knowledges.

The BoK2019 event space was designed as a meditation on conferral. The aims of the conference program structure, in terms of the spatial, social, and enactive field being crafted for conferral, exchange, learning, and performing and reperforming the knowledge being imparted, were to petition and re-petition the attention of attendees to become participants and not lapse back into a passive observer mode. This was achieved by emphasising that everything—every event, session and activity—was a mode of conversation. The keynotes were devised as conversations between two presenters which opened out to a conversation with delegates. These interactions provided opportunities to position and offer perspectives that would then be engaged by a keynote with knowledge in another fields. This innovation acted as an enabling constraint, a term used in cognitive psychology and ftheories of cognitive development and epigenesis to describe how any component in a system is not independent of that system.26 More recently the notion of enabling constraints has been deployed to describe practice-led research or research

creation, specifically, the way concepts become embodied guides for perception and action, thinking and feeling to move from ‘work to world.’27

Great care was taken in pairing the keynote and presenter and introducing them to each other well in advance of the conference, an action that allowed them time to talk and plot out a set of common issues and concerns that they could develop across their areas of interest. Notable sessions, such as Margaret Wertheim and Annalu Waller, were instances where artist, mathematician, and disability designer came together to discuss the materialisation of ideas.28 As organisers of the event, we deliberately opted to ‘converse’ rather than to ‘confer’ as a way to counteract the tendency to have already-agreed upon sets of values and assumptions that underwrite and drive the event. The challenge was to find ways to seed every occasion for potential conversations.

The key points for discussion that can be identified at the intersection of academic research conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals is the ripple effect that alternative modes of knowledge acquisition and production have on communities of practice. One issue in particular stands out in need of discussion: the way in which a practitioner, having built up an embodied practice that activates alternative, material, experiential and neuro-diverse modes of enactment, deals with the ‘languaging’ of their practice. When knowledge is acquired through doing, making, moving, or bringing one thing into relation with another, the impact does

vol. 17, no. 022020

co-constructingbody-environments

21

enacting bodies of knowledge

jondi keanerea dennis

meghan kelly