“Abortion is rarely easy, but hypocrisy and misogyny make it tragic for many women. Ian Radforth’s reclamation of Jeannie Gilmour provides a moving reminder of women’s long-standing efforts to command their own bodies and destinies. The history of this unnecessary death may be Victorian, but the message is right up to date. It’s always good to get the real villains straight.”

—Veronica Strong-Boag, Professor Emerita, Department of History, University of British Columbia

“At a twenty-first-century moment, when abortion, gender, class, ethnicity, inequality, and the law dominate headlines and galvanize public discourse, Jeannie’s Demise reveals the riveting, tragic tale of 23-year-old Jeannie Gilmour. With the deft hands of a master storyteller, Ian Radforth forcefully reminds us how the past speaks to the searing issues of today, weaving a gritty and captivating narrative that is as compelling and sad as it is informative and illuminating. Jeannie’s Demise is a fantastic addition to Toronto history, legal history, and social and cultural history—and a reminder that the divisive political issues of the past are always present.”

—Dimitry Anastakis, University of Toronto, author of Death in the Peaceable Kingdom: Canadian History since Confederation through Murder, Execution, Assassination and Suicide

“With great skill, compassion, and empathy, Ian Radforth cuts through the voyeuristic and often judgmental press coverage of the trial to bring humanity to Jeannie Gilmour and those on trial for her death. Radforth’s meticulous research and eloquent writing paint a vivid picture of the politics, culture, and religious values that influenced Gilmour’s decisions and restricted her choices. Jeannie’s Demise is a story about how one woman navigated these politics in Victorian Toronto, when abortion was illegal. But it will resonate with reproductive justice activists today, who continue the increasingly difficult work of defending people’s control of their reproductive health.”

—Nancy Janovicek, Department of History, University of Calgary

“A gripping tale of the grim realities of abortion in nineteenth-century Canada—vulnerable womanhood, sleazy medical quackery, and convoluted criminal justice—told with compelling clarity and insight. And a powerful cautionary tale for any attempt to recriminalize women’s right to choose.”

—Craig Heron, Professor Emeritus, Department of History, York University

“What a remarkable achievement! Radforth brilliantly uses one sensational murder-by-abortion trial in nineteenth-century Canada to illuminate the everyday world of women and men as they wrestled with conflicting religious messages, fiercely patriarchal traditions, a slowly changing sexual order, and the urgent need to protect honour, reputation, and property. Jeannie’s Demise provides an intimate and vivid portrait of the precarious, treacherous worlds of ordinary people in Victorian Toronto.”

—Ian McKay, Wilson Institute for Canadian History, McMaster University

“Rich in detail, meticulously researched, this book will delight those wanting to know more about the history of abortion and of Canada’s criminal justice system.”

—William Wicken, Department of History, York University

“Victorian Toronto is often portrayed as a genteel place, but Jeannie’s Demise reveals that the reality for many was very different. With his exhaustive research, Ian Radforth provides a vivid window into the social history of nineteenth-century Canada, with details and characters that bring us right to the streets of Toronto.”

—Shawn Micallef, author of Frontier City: Toronto on the Verge of Greatness

“Ian Radforth demonstrates a timeless truth—that when women’s rights to abortion are denied, women pay with their lives. In this impeccably researched and beautifully written study, Radforth creates a vivid sense of time and place, masterfully weaving the personal and familial stories into the larger social, legal, and political context. In his gripping account of the dramatic criminal trials that followed, Radforth also conveys Jeannie’s dignity, spirit, and strength, and the inequities of law, patriarchy, and class in nineteenth-century Toronto. It is a must read.”

—Shelley AM Gavigan, Professor Emerita & Senior Scholar, Osgoode Hall Law School, York University

Ian Radforth

Between the Lines

Toronto

Jeannie’s Demise

© 2020 Ian Radforth

First published in 2020 by

Between the Lines

401 Richmond Street West

Studio 281

Toronto, Ontario M5V 3A8

Canada

1-800-718-7201

www.btlbooks.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Between the Lines, or (for copying in Canada only) Access Copyright, 69 Yonge Street, Suite 1100, Toronto, ON M5E 1K3.

Every reasonable effort has been made to identify copyright holders. Between the Lines would be pleased to have any errors or omissions brought to its attention.

Cataloguing in Publication information available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 9781771135139

Designed by DEEVE

Printed in Canada

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing activities: the Government of Canada; the Canada Council for the Arts; and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Arts Council, the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program, and Ontario Creates.

Praise

Copyright

Preface

Maps

Introduction

1. Jeannie and Her Family

2. Arthur and Alice

3. The Preliminary Hearing

4. Another Abortion Death

5. Botched Abortions

6. The Davis Trial

7. The Trial Continues

8. On Death Row

9. In Pursuit of the Seducer

10. Accessory after the Fact

11. Kingston

12. A Victorian Tragedy

Notes

Index

About the Author

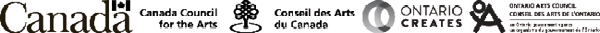

Map of Toronto’s Central Area, 1875

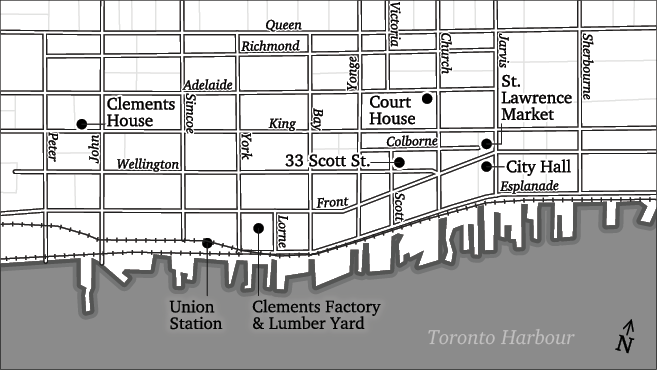

Map of Toronto and Outskirts, 1875

The Globe building

Toronto, 1869

Doe Lake

John Gilmour’s lots on Doe Lake

Arthur Davis’s business card

Alice and Arthur Davis

Scott Street, 1880

Yonge Street, 1867

City Hall and No. 1 Police Station

Toronto Jail

Chief Const. Frank C. Draper’s “Information and Complaint”

Cover of A Defence of Dr. Eric Benzel Sparham

York County Courthouse

Joseph Curran Morrison

Malcolm Colin Cameron

Edward Blake

The Queen’s Hotel

John Hillyard Cameron

Kingston Penitentiary

To her horror, a young, single woman in 1875 Toronto found herself pregnant. Anxious to avoid the shame of giving birth to an illegitimate child, Jeannie Gilmour turned to a married couple who performed abortions, without having a physician’s licence or formal medical training of any kind. The clumsily conducted, brutally painful operation was carried out at the abortionists’ home on a side street in the heart of the city. Jeannie died soon after she miscarried. The abortion providers then took steps to hide the body and distance themselves from her death. They were unsuccessful and they came before the courts. Jeannie Gilmour’s demise provides a window onto the society and culture of Victorian Toronto, particularly regarding the law and abortions.

All abortions were illegal in 1875 Canada. The law, of course, did not end abortions. Rather, it drove much of the business into the untrained hands of men and women who sought to profit from desperate women seeking the service. The risks to the health and lives of these women were enormous.

In today’s Toronto abortion is legal, but recent developments in the United States demonstrate the fragility of abortion rights. Jeannie’s story is a reminder of the risks to women when abortion is a crime.

I want to thank several people who assisted in the completion of this book. My good friend Paul Eprile took a keen interest in Jeannie’s story from the start, and throughout the research and writing he was a constant source of encouragement, wise advice, and unpaid editorial expertise. Friends who read parts or all of the manuscript and offered stimulating feedback deserve acknowledgement here: Debbie Honickman, Donna Gabaccia, Jeffrey Pilcher, Chris Raible, Kathy Scardellato, and Mariana Valverde. I appreciate the learned advice I received when I presented a paper on the topic to the Osgoode Legal History Workshop. I especially am thankful for the feedback of Carolyn Strange, who urged me to turn a chapter into a book, and of Jonathan Swainger, who shared research notes. I appreciate the early encouragement of Constance Backhouse and William Wicken. The questions at my talk to colleagues at University College, University of Toronto, were very helpful. At Between the Lines, my editor, Amanda Crocker, has been in my corner from the start, and Devin Clancy has handled production with care. Tilman Lewis, copy editor extraordinaire, smoothed my prose, clarified the narrative, and saved me from making many slips. Nathan Wessel produced the maps with promptness and skill. My partner, Franca Iacovetta, was wonderfully supportive all along, not least because this, my first retirement project, kept me occupied, which enabled her to get on with her own historical research and writing.

Toronto’s Central Area, 1875

Toronto and Outskirts, 1875

Shortly after dawn on Sunday, August 1, 1875, Charles Lovell, a foreman for the York County roads department, made a discovery on his morning walk. Lovell was ambling along Bloor Street, close to his home in a sparsely populated area just beyond Toronto’s western boundary, when something caught his eye. In the dry ditch lay a new pine box about the size of a coffin, partly covered with earth and sods. Lovell stepped down into the ditch and lifted one end. Something rolled. He saw blood. Lovell fetched a couple of nearby residents, who agreed that a constable was needed, so Lovell sent a boy to find one. Growing impatient, Lovell took an axe and broke open the box. Inside he found some straw, a white chemise, and the naked body of a young woman.

A few hours later, Coroner E.C. Fisher held an inquest nearby at Mrs. Mantle’s Robin Hood Hotel on Dundas Street. Two physicians, who had already performed a post-mortem examination of the body, reported that the deceased was an otherwise robust and healthy woman whose death was caused by a violent abortion. The jury at the inquest concluded that there had been a wilful murder of “an unknown woman” by some “person or persons unknown.”

Police believed they knew who those persons were. The evening before the discovery, Robert Campbell, a night watchman on duty in the city centre, reported to police that he had seen a heavy new pine box being removed from 33 Scott Street, the home of well-known abortionists “Dr.” Arthur Davis and his wife, Alice Davis. (The press invariably used quotation marks because Arthur Davis was not a licensed physician.) Henry Reburn, the detective on duty at nearby City Hall Police Station immediately went looking for the box. He failed to find it. However, the following day, when Det. Reburn and his associates learned about the discovery on Bloor Street, they surmised that the woman in the box had died as a result of an abortion performed at the Davises’ home. Det. Reburn and his colleague John Newhall went to Scott Street and laid murder charges against Arthur Davis, thirty-four, and his wife Alice, twenty-three.

In the hope that the young woman might be identified, descriptions of the body appeared in Monday newspapers. The still naked body was placed on display in the city’s dead-house. After some misidentifications, late Monday evening police were persuaded that the body was that of Jane Vaughan Gilmour, a twenty-three-year-old single woman, the daughter of a Baptist minister.

Jane—or Jeannie as she was called by those who knew her—had arrived in Canada from Scotland in 1872 with her parents and siblings. While the rest of the family set about clearing a farm in the District of Parry Sound, Jeannie worked as a domestic servant near Woodbridge and then in Toronto.

Newspapers eagerly reported the discovery of the body and the findings of the inquest. Toronto’s three daily newspapers featured the story. The Globe provided many details of what it headlined “The Fatal Abortion Case.” In an article titled “A Dreadful Crime,” the Mail reported that “considerable excitement” had prevailed in the city on Sunday as the facts of the case became known about town even on the Sabbath, a day without newspapers. In its report, titled “Atrocious Crime,” the Leader said that the unknown victim was thought to be “of very beautiful features and evidently one which has lived in a station far above work.”1 Even before her identity was known, then, the press showed sympathy and admiration for the deceased because she was white and apparently refined. Once aware of her Scottish identity, the press’s sympathy only increased for her as a wronged female. Being Scottish in Victorian Toronto meant that Jeannie Gilmour was British, and so part of the city’s mainstream, and that she came from a part of the United Kingdom that had produced many of Canada’s prominent men. Being a minister’s daughter reinforced her respectability at a time when, for most Torontonians, the Christian religion mattered greatly and clerics were highly regarded.

Newspapers beyond Toronto soon picked up the story of the heinous crime. The Rochester Express recognized Arthur Davis as having escaped Rochester while under indictment for procuring an abortion there. It regretted that quacks like Davis easily found sanctuary in Canada. “We hope,” declared the Express, “the authorities of Toronto will not let up on Davis until he swings from a rope.” The Cincinnati Enquirer headlined its story “A Clergyman’s Daughter Murdered in an Abortionist Den.” It suggested that Jeannie Gilmour had been “subjected to humiliations against which her sensitive nature must have bitterly revolted.” As more information about the Gilmour case came out in the following weeks, the Globe called the Toronto case “disgusting and terrible,” and another publication said that, “for cold-blooded brutality,” it had “probably never been equaled.”2

Journalists saw the case as being similar to the Trunk Mystery, a sensational case where the body of a woman killed by a botched abortion in 1871 was found abandoned and concealed in a trunk in the luggage department of a New York City railway station.3 Readers were also reminded of an 1868 case involving high society in Montreal. Robert Notman, the son of the famous photographer-to-the-wealthy William Notman, was convicted of murder for procuring an abortion that caused the death of a young woman training to be a teacher. In the wake of her death, the doctor performing the operation swallowed prussic acid and died.4

Jeannie Gilmour’s fate fascinated Torontonians for months. Further charges, police court revelations, and three trials kept the public enthralled from August 1875 until the end of January 1876. City newspapers lavished attention on developments, some of them gruesome, some shocking, all of them made more serious by the fact that conviction meant the death penalty. Much was at stake.

To add to the drama, the evidence showing what had occurred in the home of the abortionists at the end of July was never complete. Mysteries persisted. It was assumed that some man had taken advantage of Jeannie Gilmour’s innocence and seduced her, and speculation swirled regarding his identity. Just as mysterious and perplexing was how a minister’s daughter, hitherto impeccably respectable, had ended up at the office of abortionists who charged prices far beyond her means. Moreover, people pondered what the demise of a respectable young woman said about the state of morality in the city. They asked how abortionists were able to persist in practising their illegal and dangerous trade in the heart of town. It was hard to reckon in Toronto the Good, where it was widely believed that British law and order prevailed, churches flourished, and public morality was appropriately regulated.

Most of the historical evidence about this case comes from Toronto’s three daily newspapers, which in 1875 were sharply partisan political journals. The Globe was the voice of the Liberals (often referred to as Reformers, harking back to the party’s roots), who held office in Ottawa and Toronto. The Leader and the Mail supported the opposition Conservatives, or Tories. The newspapers also took a keen interest in municipal politics, where in 1875 the Tories dominated council. Toronto’s political dailies made room for dramatic local developments like the discovery of Jeannie Gilmour’s body, the arrest of her abortionists, and the trials that followed.5

These daily newspapers only loosely resemble the press of today. There were no photographs and few illustrations, with the exception sometimes of editorial cartoons. The papers were slim, the type tiny, the columns cramped. These papers did not undertake investigative journalism, so they remained silent on many matters where today we would expect to find information. Journalists seldom presented interviews with the principal players in their stories and almost never interviewed ordinary people in the street.

In 1875, Toronto was a bustling place, and indeed it had always been a meeting place. Toronto’s history begins with the Indigenous Peoples. The Haudenosaunee, the Wendat, and the Mississaugas all made use of the land that is now the Greater Toronto Area. At times competing and at times allying, they were drawn to the place by the rivers that empty into Lake Ontario, waterways that provided access to Georgian Bay and had rich salmon fisheries. Soon after the end of the American Revolution, British colonial authorities took a renewed interest in what remained of British America. Negotiations were undertaken with local Indigenous Peoples along the north shore of Lake Ontario. The Toronto Purchase of 1787, a deal struck between the British Crown and the Mississaugas, began a process that pushed Indigenous people from the Toronto area. A growing wave of colonists, both from the United States and Great Britain, resettled the area.6

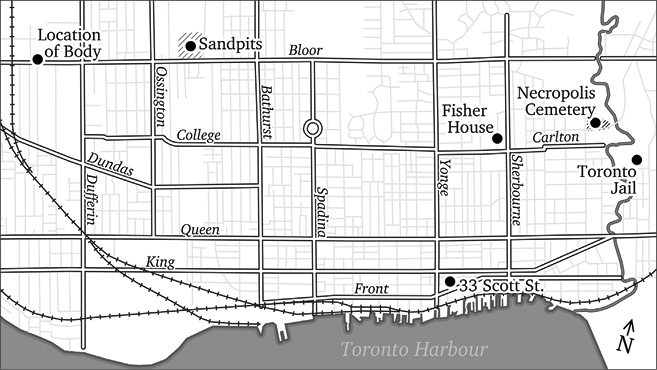

The King Street East home of the Globe, Toronto’s Liberal newspaper. Photographer: Noverre Bros., 1871. Toronto Public Library.

By 1875, Toronto ranked as the largest city in the province and had become the capital of Ontario when the new province was created in 1867. It was also the administrative centre of York County and thus the location of the county court where the Davises would be tried. Railways built two decades earlier had stimulated the city’s commercial activity, which had previously been dependent on the seasonal rhythms of its lake port. Agricultural products and timber from the rich hinterland, no longer controlled by Indigenous Peoples, streamed through town, destined for Canadian, American, and British centres. The advent of the railways also stimulated industrialization in the city. Small shops and growing factories churned out large quantities of manufactured goods—metal, food, furniture products, and more—mainly for Canadian markets. Commercial and industrial activity fuelled the growth of banks, mortgage companies, insurance firms, and a publishing industry, adding white-collar jobs to Torontonians’ occupations. Horse-drawn streetcars provided cheap transport along the main thoroughfares, but telephones and electricity were still about a decade in the future. It was the telegraph that connected people, and gas lamps that lit the streets at night.

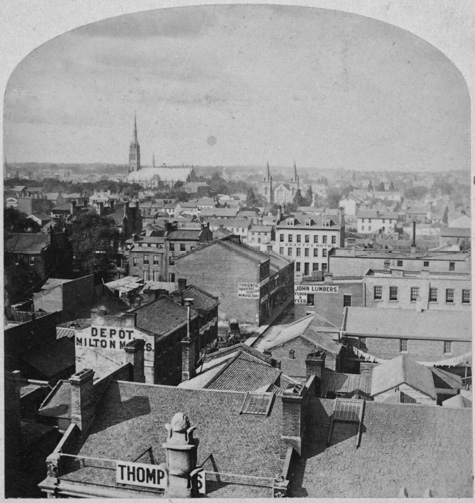

Toronto, 1869. Looking to the northwest from the roof of St. Lawrence Hall and showing the part of the city where the abortion and trials took place. Photographer: William Notman. Toronto Public Library.

Toronto was a stratified city where large employers, successful investors, and privileged old families held most of the wealth and power. Far more numerous and more precarious were its working people, drawn to town by jobs. In the 1870s, class consciousness was becoming pronounced, as manufacturers formed associations to advance their interests politically and many skilled workers formed trade unions and risked strikes to challenge their employers. An economic downturn, which began in 1873 and was still sharply felt in 1875, turned the city into a magnet for unemployed men looking for work.7

Toronto’s long-term economic vibrancy had drawn immigrants with roots in the British Isles. By 1875, Toronto had a population of about fifty thousand, composed nearly entirely of English-speaking people with origins in Ireland, England, and Scotland. The city’s Black, Jewish, and Indigenous populations were tiny, and there were even fewer non-English-speaking people.8 Immigrants from Ireland had come mainly from its minority population of Protestants, some of whom brought with them a militant anti-Catholicism. Roman Catholics, overwhelmingly of Irish origin, made up about one-fifth of Toronto’s population, forming a minority resolved to flourish.9 The city’s most obvious social tensions centred on the clash of Protestants and Catholics. In 1875 the largest riots in the city’s history pitted Protestant militants against Catholic religious processionists who had been urged by their archbishop to march in celebration of the pope’s declaration of a Jubilee Year.10 The criminal court decided the fate of the arrested Jubilee rioters on one of the days that it was hearing testimony regarding the Gilmour–Davis case.

The weight of the law came down upon the Davises. Women had long sought abortions to end unwanted pregnancies, but the law aimed to constrain their attempts to limit family size in this way or to avoid the social disaster of bearing a child out of wedlock. In 1841 the province that became Ontario got its first abortion law, which made it a felony to procure an abortion (“a miscarriage”) by either administering poison “or other noxious thing” or by the use of any instrument.11 Abortion law in the mother country provided the model for the colonial statute. An earlier English law had prohibited only abortions after quickening, that is, at about fourteen weeks after gestation when the mother felt the fetus move. Many people believed that that was when life began. By 1841, Britain had eliminated the quickening distinction, so Ontario law also made abortions illegal at any stage. It is likely, however, that many women continued to make the distinction, feeling more ready to seek an abortion before that stage, the law notwithstanding. The condemnation of abortions in public discourse and by the law probably contrasted with more tolerant popular attitudes and practices.

After Confederation in 1867, the criminal law fell within Ottawa’s jurisdiction. At the time of the Gilmour–Davis case in 1875, abortion was an indictable offence under Canada’s criminal law.12 All abortions were illegal, even when pregnancy would mean death to a woman carrying a fetus. Abortion providers, as well as women who performed abortions on themselves, could be sentenced from two years up to life in prison if convicted. Individuals who supplied drugs or instruments knowingly used for abortions were guilty of a misdemeanour and subject to penalties of up to two years. When a woman died as result of an abortion, the procurers of her abortion faced murder charges and, if convicted, the death penalty was mandatory.13

By no means did these severe laws prevent abortions from taking place. Countless women had abortions—how many we have no way of knowing. Authorities remained unaware of the vast majority of these clandestine occurrences, or they generally looked the other way. Trials for abortion were infrequent in nineteenth-century Ontario.14 Police only laid charges when pressed to do so, for instance, by a young woman’s parents or by a physician consulted when, after an abortion, the woman’s health took a turn for the worse. Botched abortions often resulted in septicemia (blood poisoning), a condition that physicians in the 1870s were ill-equipped to treat effectively. Licensed physicians, organized since 1866 in the province’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, led the campaign against abortion, focusing on those performed by unlicensed “quacks” as part of their wider campaign to gain a monopoly over medical services.

Canadian medical men sounded the alarm about the growing prevalence of abortion. At an 1869 meeting of the Medical Branch of the Canadian Institute, Dr. Joseph Workman, a prominent physician and superintendent of the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto, maintained that abortion had “crept into Canada from the neighbouring States, where it is now, by a very large proportion of the people, regarded as an expediency of domestic economy, rather than a violation of either divine or human law.” He blamed many cases of insanity on abortions. At a meeting of the Medical Council of Ontario in 1868, Workman went so far as to claim that “he had it on authority that within the last twelve months there had been 1,000 cases of provoked abortion in Toronto.”15 His claims echoed the rhetoric of physicians in the United States who were also campaigning against abortion and quackery.16

In the ten years before 1875, only fifteen people had been charged with murder or attempted murder in Toronto.17 The murder charge in the Gilmour–Davis case was made because it was the belief of the prosecution that the Davises had caused Jane Vaughan Gilmour’s death by performing an abortion on her. It might appear surprising that the charge was murder rather than the lesser charge of manslaughter. After all, the abortionists’ intention was not to slay Jeannie, and manslaughter charges, with their lesser penalties, normally apply in cases where there is no intent to kill. However, under British and Canadian law at the time, when an individual caused a person’s death in the course of committing a felony, the charge could only be murder. Abortion was a felony, and so authorities charged the Davises with murder. It was a capital crime. If the accused were convicted, the only possible sentence was execution by hanging. After a death sentence, however, there remained the possibility of a commuted sentence. Canada’s governor general, acting on the advice of cabinet, had the power to issue a stay of execution and to reduce the sentence, normally to life in prison. It was always uncertain whether the Crown would show mercy in a particular case.18

When Arthur and Alice Davis were arrested for murder on August 1, 1875, much needed to be determined about how the young woman had ended up in their deadly hands, and whether the Davises would be convicted and sentenced to death. The city anxiously—and eagerly—waited for developments.